Becoming the Bostock Brothers: The family behind New Zealand’s organic powerhouse

John Bostock (centre) pioneered commercial organic apple growing in New Zealand; his sons George (left) and Ben (right) have built the country’s largest organic chicken business.

A family at the forefront of large-scale organic food production offers perspectives on their motivations and the potential implications for consumers and exports.

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Tessa Chrisp

In the 1980s, Hawke’s Bay apple grower John Bostock’s wife Vicki told him their use of agri-chemicals was over. “That’s it. No more harmful stuff on land near our three little boys.”

John accepted Vicki’s edict and replied: “Okay, darling, I’ll go away and figure out how to make that work.” Like the Oncler in the Dr Seuss classic, The Lorax, John got to “figuring”. While the Oncler was “figuring on biggering”, John was figuring on bettering.

“It took a lot of figuring, that’s for certain, but I never had a moment’s doubt that it could be done, nor did I doubt that it needed to be done.”

Third son, Tom, works with his dad at Bostock New Zealand.

But it wasn’t easy, and it wasn’t popular. “People thought we had gone completely barking mad in moving from the agri-chemical world to biologicals. We were suspected of having turned into mung bean-eating, sandal-wearing hippies.”

Being labelled a hippy was no deterrence, but the campaign against organics was another matter. John was well aware of the importance of health; his cardiologist father and his mother emphasised eating lots of vegetables, avoiding smoking, keeping fit and avoiding being overweight. But it is undoubtedly the late Vicki and her instinct to protect their three young sons, Ben, George and Tom, from harmful chemicals that drove the family into embracing the then little-known philosophy of organics.

The Ngatarawa Stables, built by a Glazebrook forebear of John’s late wife Vicki, have seen many comings and goings over the decades, including training the 1977 Melbourne Cup winner Gold And Black. It also produced many an award-winning Ngatarawa Wine when Alwyn Corban and Garry Glazebrook owned the property before John. Today, the handsome wooden buildings are used for wine tastings, family functions, and to host stockists.

“It is not just that we were totally alone, but we faced real opposition. People predicted that we would bring down pestilence and spread disease because we were not spraying the necessary chemicals. It is hard to believe now, but a compulsory regime for commercially grown apples required 10 organo-phosphate sprays throughout the season. It was like a nuclear war programme.”

At the time, all of New Zealand’s export apples were sold by a single-desk seller, the Apple & Pear Marketing Board, and the spray programme was to convince overseas markets that Kiwi apples were free of leaf roller pests.

John believes the Apple & Pear Marketing Board did a perfectly bad job by convincing would-be organic apple growers that there was no market for organic fruit and convincing would-be organic apple purchasers that there was no production of organics.

It’s best not to get John started on monopolies. Suffice, he says, that the initial case for managing exports that way had well and truly run its useful course by the time he was fighting for the right to export chemical-free apples. “It is hard to believe I couldn’t sell my apples at our orchard gate. A Soviet apple farmer was freer than I was in those days.”

There’s a place for government, and he thinks government energy today could usefully be directed towards developing markets for horticultural exports. “There was a time when there was a huge push for New Zealand to export, great enthusiasm for horticulture, and everyone was trying new crops and products. We saw the birth of the kiwifruit and squash industries, and it was exciting; export subsidies and tax breaks for exports and an almost patriotic zeal to export with a feeling that we were alone in the world and that New Zealand had to earn its way.

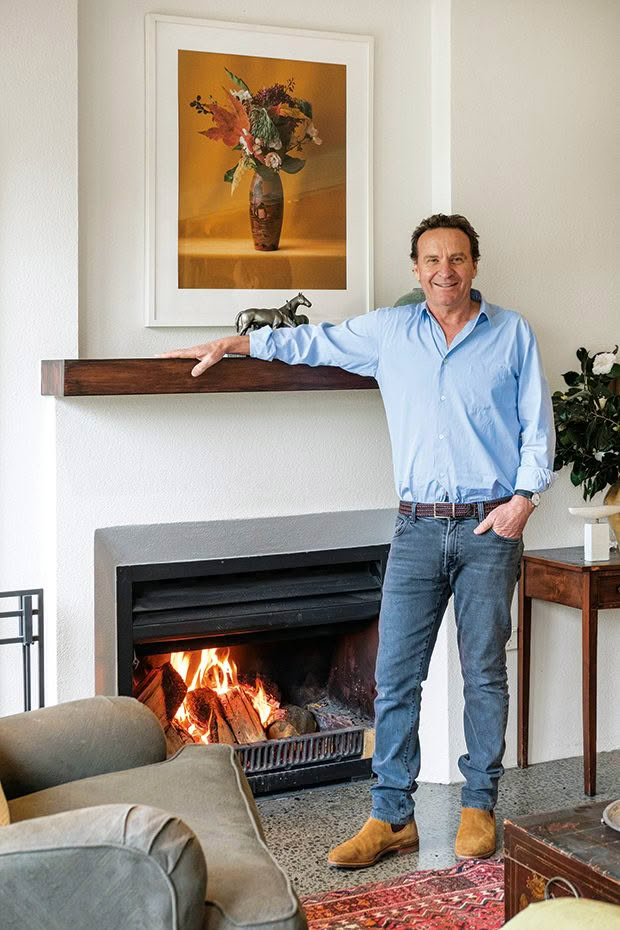

The Bostock family home, where John and Vicki raised the three boys, is now home to George, who purchased it two years ago. George had been working on superyachts in the Mediterranean and came home in 2016 before joining Ben in his business shortly after.

“It would be very valuable for the government to add value to our exports, so our products are at the premium end of the market. Brand NZ is powerful wherever you go. Enhance that and open trade doors.”

Horticulture, says John, is a fraught business with disaster never too far around the corner. Cyclone Gabrielle’s significant impact on Hawke’s Bay fruit and vegetable harvest sent Bostock onions washing up on Gisborne beaches and to the north and south of Hawke’s Bay and left apple orchards with unbelievable damage.

“You must look beyond it, accept it as part of nature, and stay positive. I am always amazed that I can find the positive when things are going badly. It is an acquired habit, and you must push yourself to keep upbeat. We have so much to be grateful for — and, in the business, all the fundamentals are there. We keep going.

Ben (left), his wife Nicki and their three boys, Jack (9 months), Charlie (3) and Archie (6), who live close to Hastings, are regular visitors to the old family home.

“Hey, today the sun is shining. It is dry, it has stopped raining, the markets are good, organics are in demand and we can turn the page on the cyclone.”

Bostock New Zealand is today the largest producer of organic apples in the southern hemisphere and New Zealand’s biggest exporter of organic apples. John is proud that the apple hasn’t fallen far from the organic tree when it comes to his three sons.

The youngest, Tom, works with John in Bostock New Zealand, and his other two sons, Ben and George, are the Bostock Brothers — New Zealand’s largest producer of organic chickens.

- Chester the dog is wondering if dinner time is around the corner.

Organic chicken farming is a process they pioneered and developed, like their father, by figuring it out themselves.

“They are wonderful, wonderful kids,” says John of his three boys. “Vicki did an incredible job of bringing them up while I ran around in small circles.”

The boys might remember it slightly differently; yes, without any doubt, their mother was a legendary and much-loved figure not only in their lives (she died in 2015) but in the wider Hawke’s Bay community, but they also credit their father with showing them how to tackle challenges and solve problems.

- Baby Jack enjoys the fun from his mum’s knee.

- The house was originally designed by architect Nick Bevin.

The organic chicken business was initially Ben’s brainchild. He is a science and physics graduate from the University of Otago. He worked in Australian mines, farming in Britain and then as a New Zealand-based meat trader before setting off on an organic path. He was propelled by a desire to grow healthy food in a process he could control from paddock to plate — bypassing middle-men ticket-clippers. His research with organic chicken growers in France convinced him there was a market for a vertically integrated organic chicken-farming business producing tasty food in an environmentally healthy process. (See NZ Life & Leisure, November/December 2014.)

Chickens à la Bostock Brothers lead a charmed life of natural foraging and free-ranging in open paddocks. Slow growth and organic feed promote flavourful meat.

Being convinced it was a worthy enterprise was perhaps the easiest part of what Ben — and later — brother George, who joined him in business, have achieved. Bostock chickens have a dream life — so far as a chicken’s life goes. They free-range under apple trees in organic pastures, live in custom-built chalets imported from France, feed on organic maize grown in the paddock adjacent and listen to classical music. When the end comes, they are caught two-handed by a human and placed in a clear box for a pleasant view of their final short journey to the purpose-built Bostock abattoir in Hastings. In a chlorine-free process pioneered by Bostock Brothers, the meat is chilled and processed before being distributed nationwide.

The brothers supply the market with a million birds each year, but Bostock Brothers is still small when it comes to the country’s overall chicken consumption, accounting for one per cent of the chicken meat industry.

Ben studied organic chicken farming in France before importing chalets in 2014 that allow the chickens to free-range. Partial to classical music (which calms them), the birds were recently treated to a live concert by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. Organic maize, grown in the adjacent paddock, is a significant part of their food.

Ben and George enjoy working together without too many hard and fast rules about what role each takes; George tends to manage marketing and distribution while Ben runs production and the facilities. It’s all about the total trust they have in each other.

“We are chipping away at growing our business, building up our good distribution through supermarkets, retailers and food service before we tackle overseas markets. It is a deliberate strategy to put the New Zealand market first.

“We have to come up with crazy ideas to solve problems, and it is a great journey that we have both loved.”

- George’s single-engine Cessna aircraft accommodates three friends with bikes for weekend mountain biking adventure.

Maybe one day, this generation of Bostocks will be the southern hemisphere’s largest producers of organic chickens. Their dad, John, certainly believes the boys’ chicken business has plenty of capacity to grow. Not that growth is a goal for its own sake, but a necessary part of earning decent export receipts for New Zealand.

“You can’t talk to a retailer in the United States like Whole Foods or Costco without having the volume and scale,” says John.

Not that he is too eager to give advice. “I try to support them, and if I’m not asked for advice, I try my hardest to shut up.”

BOSTOCK NEW ZEALAND

The original Bostock home is bounded to the south by a thick shelter of native bush planted by his parents, who competed to prove their growing methods were best. The trees, 30 years later, are much the same size despite skullduggery and interference with each other’s water systems. Behind the stables is the old Washpool Farm.

• will export 1.4 million boxes of organic apples in 2024 — a hefty contribution to New Zealand’s export receipts

• is the country’s largest producer of organic apples (85 per cent of NZ’s organic export crop)

• is the largest exporter of organic apples in the southern hemisphere

• has 2500 hectares of land under intensive horticulture in Hawke’s Bay

• also produces organic onions, maize, grapes, squash and apple cider vinegar

• employs 1000 staff at the season’s peak.

• is Aotearoa’s only Fairtrade-certified horticultural business, providing a significant fund managed and distributed by a workforce committee annually for various projects, including driver licenses, educational opportunities, dental care, housing, irrigation and school facilities in Pacific islands

• is BioGro NZ-certified to create healthy living soils that benefit ecosystems and produce less pollution than conventional farming.

BOSTOCK WINES

• produces wines in limited quantities in years when the grapes are of sufficient quality (thanks, La Nina, for the cold, wet seasons of 2022 and 2023, with no Bostock vintage in either year)

• has organic vineyards on the old Washpool Farm grazing paddocks near the landmark Ngatarawa Stables and homestead where John’s late wife Vicki (nee Glazebrook) grew up and John and Vicki raised their three sons

• hand-harvest grapes of the pinot noir, chardonnay, syrah and pinot gris varieties

• are available online at bostockwines.nz and from Ngatarawa Stables.

BOSTOCK BROTHERS

• produces one million chickens a year, more than any other organic producer

• has a staff of 65

• commands one per cent of the New Zealand chicken meat industry.

JOHN BOSTOCK’S ADVICE FOR ENTREPRENEURS

Photo: Florence Charvin

Hang in there. Don’t give up at the first or second knockback.

It is a highly competitive world, and the knockbacks will come from every direction, whether compliance, unreliable people, changing markets and customers — even the weather. Sometimes, it seems like the whole world is against you, but you must keep going. And keep smiling.