Auckland makerspace space Hackland is a grown-up playground for building and making

In Hackland, the grown-ups learn the same way kids do – by trying new things and having fun.

Words: Mikaela Wilkes

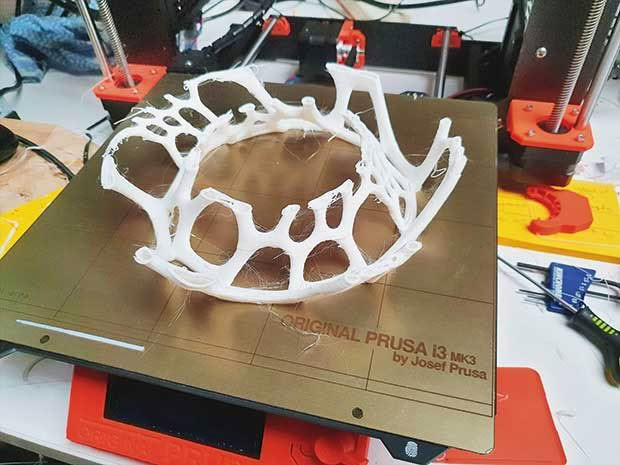

Hackland is a creative space, founded by Joran Kikke, where grown-ups can do whatever they please. There are laser-cutters, 3D printers, soldering irons, bins of electronics, no specified projects and no deadlines.

Hackland’s atmosphere is similar to kindergarten arts and crafts time, with power tools instead of Lego, a soft Indie-music playlist and beer.

The purpose of “makerspaces” is to provide a social area full of (often expensive) materials and tools for people to work collaboratively on projects of interest. These can include carpentry/engineering workshops, sewing/textiles and computer-science/robotics labs. But unlike solo inventors, “makers” aren’t trying to specialize in anything particular, or to profit from their creations.

The goal is to cross-pollinate ideas, expertise and resources simply for fun, and to see what happens. A collapsible wooden dingy, a cardboard air conditioner and a nursery full of plants rescued from Bunnings’ bins are some of Hackland’s projects.

The rule is: “If you want to change something and it would take less than six hours to undo it, you don’t need permission.”

Its two buildings in the Auckland suburb of Kingsland are open to the public once a week, and 35 regular members pay a $15 weekly fee to cover the rent. Three hundred casual makers pay a koha or nothing to visit. There is a focus on creating with, rather than consuming, existing products. Hackland itself was made just one year ago.

Joran says he’s been taking things apart since birth. At 26, he encountered his first makerspace in London and it reminded him of life on his family’s farm near Lockerbie in the south of Scotland.

Joran picked up his electrical skills by tinkering. He believes being allowed to experiment with new tools, to try and fail, or to see others working with familiar things in ways that are unfamiliar, is how we learn best.

Joran and his partner Helena Teichrib felt that existing makerspaces in Auckland, largely arranged by the Auckland Council, weren’t malleable or autonomous enough for a community to form. “A lot of money went into them, but they sort of missed the point. So, we decided to start our own.”

They found six friends who were keen on the idea and signed a lease. “We worked out we needed only 10 to 15 people to join to afford it, and after that, it wasn’t so scary.”

They put the bare minimum in place: internet, power, desks (donated) and “everything else you see here happened because people got excited and brought things”. Hackland is always open to its members. Everyone has a key and is equally responsible for the environment.

“Handing over the keys to our members made running this place easy.” Although, it does get messy. “Eventually you won’t be able to get to the things you want to get to. But that’s OK. The loudest complainers will eventually convince their fellow makers to tidy up again, a bit like a flat kitchen.”

Joran is a software developer by trade. Many makers come from IT backgrounds, but there are also boat owners, professional metalworkers, builders, machinists and families who bring their children. Most of the resources are donated.

Local manufacturer Rex Robotics provides boxes of pricey Swiss-made batteries and parts that aren’t 100 per cent up to spec. Some of their small electrical motors are worth $300 each.

A South Auckland junkyard lets the makers forage for parts for free. Making is often upcycling because “the materials that have no cost are the best materials. A lot of stuff comes from building sites.”

One maker plans to programme a computer-controlled robot arm, discarded by a Whangarei welding business, to do joinery on tiny houses. He’s never used the machine before.

“I think the people who know about us trust we’ll do something good with these valuable things. Something that’s better than having them in a landfill.”

Joran’s most rewarding experience so far has been a South Auckland school using Hackland as a blueprint to set up a makerspace for kids. “Their space is working. They say they don’t know why but the children are relaxed there.” He says it’s incredible what people will do when the pressure to create for commercial reasons is removed.

“I don’t think of making as counter-culture. I think it’s our real culture.” Because at any age, people are still curious.

WHY JOIN A MAKERSPACE

Being a maker doesn’t require skill, only enthusiasm.

“Here you can jump on a machine that some people train for years to use,” says Joran. “We can have a professional run you through how to operate something like the robot welding arm in three days.”

For more green living and eco ideas see our new special edition, In Your Backyard: Living Lightly

MORE HERE:

Thinking caps on: Offcut’s hats made from upcycled fabric bring sustainability and fashion together

Weaving a future through bespoke handwoven textiles on a World War One loom

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.