Why this artisan cheesemaker doesn’t get paid

The award-winning owners of Lonely Goat say the costs of compliance are nothing to yodel about, and explain why they are working for love, not money.

Words: Helen Frances Photos: Helen Frances & Bevan Conley

Who: Rae and Brian Doughty

What: Lonely Goat artisan cheeses

Where: Brunswick, 15km north of Whanganui

Land: 90 ha (222 acres)

Web: www.lonelygoat.co.nz

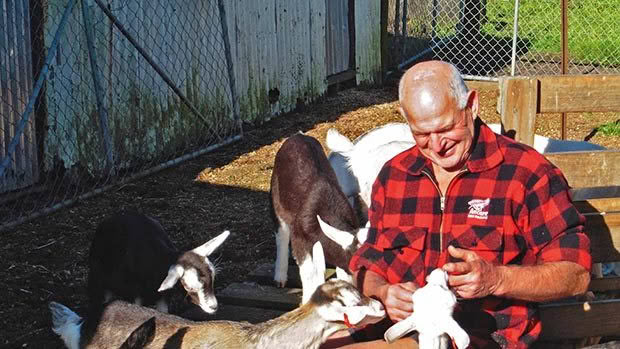

A bunch of excited kids crowds around Brian Doughty for a nibble at his red and black bush shirt. These latest progeny in the 38-strong goat herd are a mix of Anglo-Nubian and Saanen, producing a good ratio of milk solids for wife Rae Doughty’s delicious, award-winning cheeses. Finn the bullmastiff is also hanging around, always ready to down any leftover cheeses or milk. Rae makes the cheeses in a purpose-built room behind the couple’s house on their farm, 15 minutes outside Whanganui. They run a herd of approximately 60 cows along with the goats, producing calves and kids every spring.

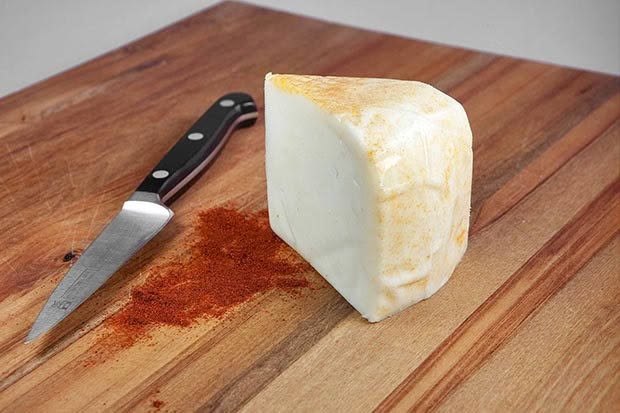

Rae’s best-selling cheese is feta, which she makes in a variety of tangy, spicy, fragrant flavours, including Tuscan, cracked pepper, chilli, and garlic. Then there’s her camembert, hard cheeses, havarti – several of which are soaking in red wine and forming a deep purple rind – cream cheese, halloumi and yoghurt. The blue cheese is segregated in its own designated fridge outside the chiller room as its flavourful mould can spread onto cheeses that aren’t meant to be blue. Rae is very good at what she does. At the 2016 New Zealand Specialist Cheesemakers annual awards, the judges awarded her Tuscan feta a gold medal and she also took home silver for her plain feta. She’s had a fast rise to this level of cheesemaking. It was only six years ago that she did a week-long course in cheesemaking at Putaruru at the New Zealand Cheese School.

“The course was great fun. We trained working in their factory. Instead of doing little 10 litre batches like I do here, we were doing 250 litres at a time. It was a big factory and it was great. I made cheese for a season in the kitchen to practice then we built the cheese room – at huge expense – and away we went.” To save money, they acquired much of the equipment second-hand. Stainless steel benches came from a café that was closing, and they also picked up a bain-marie, and five old-fashioned water-bath AGEE preservers which Rae uses to pasteurise the milk.

“The bain-marie is the most wonderful piece of equipment. When you are making cheese you’ve got to hold it at a certain temperature. Some take half an hour, others three-quarters of an hour. I can put two of my pots of cheese in it together. Feta sits for 45 minutes at 36°C. When I do the yoghurt I heat it up to 85°C, 90°C, then it sits overnight on low.”

THE CHEESEROOM

Sitting outside the door of the cheese shed are three buckets of whey for a neighbour’s pig – regulations prohibit them disposing of it down the sink. Inside, the chiller is lined with shelves of cheeses, some maturing, others ready for sale. Every cheese is labeled with its name, batch number (the date of its production) and the use-by date. Before you enter Rae’s cheese room, you have to get kitted out. There’s a white overcoat, bonnets (very scientific-looking) and rubber Crocs for your feet. You wash your hands thoroughly, then step into a sanitising footbath on the way in. It’s warm inside, spotless, sanitised, and there are temperature gauges everywhere. Rae’s grandson Nick has been vacuum packing earlier in the day. He reports the wine-marinated havarti smells fabulous and he’s looking forward to a slice or two when it’s ready in about three months time.

Rae is draining liquid off a tray of six feta cheeses. She does this around four times a day until they are the right degree of firmness. Any flavourings, such as cracked pepper, chilli or herbs are boiled and added just before the cheeses go into the moulds, once the whey is drained off. They spend 24 hours draining before she takes them out, dry salts the outside, and – when they are firm enough – cuts them and places them in a 10% brine (1 part salt to 10 parts sterilised water). Other products on the go are halloumi, a big favourite with Rae’s Wellington customers, camembert, cream cheese and yoghurt.

During the milking season, Rae delivers 10-litre, sanitised, food grade buckets of fresh goat milk a few yards from the shed to the cheese room and gets started.

From the cheese room window there’s a view of the paddocks and Rae’s tunnel houses where she grows gerberas and chrysanthemums hydroponically in one, roses in the other. The flowers are good sellers at the market and easy to maintain. A computer switches the gerbera watering system on every morning and she feeds the plants ready-made mix.

THE GOATS

Goats, while they love their food, can be picky eaters and providing substitutes to rain-fed grass is not easy. “You can hard feed them but they’re not going to milk off hard feed,” says Rae. “They are so fussy with the hay. This season too they wouldn’t eat our meadow hay. But wilt it and they demolish it. We saw two places in Sanson milking 1000 goats where they are cutting and wilting the clover hay and the goats love it.”

She gives the goats a herbal concoction every day to try and prevent parasites because if she uses a chemical drench she has to hold the milk out of the vat for 35 days. She packs tight an ice-cream container with nasturtium flowers (250g), soaks them for a fortnight in cider vinegar, strains it and adds molasses. She also uses a mineral mix called Metaboliser and thinks the goats look better since they have been having it.

“It might just be wishful thinking. They look scungy after kidding anyway (when 2-3 kids are the norm). The goats love the molasses. When they kid I give them a five-litre bucket of warm water with molasses in it and they down that like there’s no tomorrow.”

Brian was an animal technician in another life (Rae was a vet nurse) and he tests the goats’ blood for copper and selenium. He goes for the jugular with a very small needle.

“You hold the head extended and it just pops up.” The mineral supplements they give the goats compensate for the naturally-occurring soil deficiencies in their area.

THE BIG COST OF BEING A SMALL CHEESEMAKER

Rae says she is ropeable about the increased costs she has to pay to be compliant with the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) cheese and raw milk regulations, despite being small scale. Annually, Rae makes between 800kg and 1000kg of cheese. Ideally they like a season to span July through to April but in 2015 they finished milking in March because of drought which meant she made just 243kg of cheese in total. In October 2015 she made just 34kg by October 6. In the same time period in 2016 she made 75kg because there had been more rain.

But whether it’s a good year, or there is a short, dry season with less grass, diminished production and income, the compliance costs remain the same. She has been selling her cheeses for the past five years to Common Sense Organics in Wellington and Ambrosia delicatessen in Whanganui, and she and Brian also have a stall every Saturday at the Rivertraders’ Market in town. The couple estimates the costs of compliance now represent 20 percent of their income. These include the RMP (Risk Management Programme), annual inspection of the cheese room and adapted herring-bone milking shed (90 percent of which is shared with the cows); regular testing of milk and cheese curd, and monthly floor swabs.

“You’ve got to have all the paperwork to prove you have done it properly. I don’t take a wage – there’s no money in it.”At inspection time an auditor comes down from AsureQuality in Northland for a day. “Up until now she has charged $1500. She drives and does several places along the way. She looks at my cheese room and all my testing and results then I get a bill for $1500, which has been fine. But now that has gone up to $3300 for the same thing. The reason given was that there hadn’t been a price increase for five years, but that’s not our problem,” Rae says.

Brian believes AsureQuality is feeling the pinch at the moment because of competition and surmises that the government-owned food safety and biosecurity service may not have the means to compete well. Their other costs include a 32-page customised RMP (Risk Management Programme) for which they pay MPI $567 a year and for that they receive a Notice of Registration which is posted on the wall of the cheese room. A generic RMP through Open Country covers the dairy herd and is less expensive. “I am on board with most of it, the pasteurising and everything,” says Rae. “You’ve got to get it right and if you’re not heating the milk up to a certain temperature (a minimum 72°C for 15 seconds) before you make your cheese you can stuff it all up. Some people make raw milk cheeses but then they have to do extra testing and I’m not prepared to do that. I’m happy with the pasteurising.”

Rae had been selling raw goat milk to people with allergies to cows’ milk, and to those who simply like it. Up until late last year, she was required to have the raw milk tested once a month by MilkTestNZ at a cost of $47. But the new rules changed this to every 10 days at an estimated cost of $148.97 and additional tests were introduced. According to an estimate she received, the most expensive, additional test is for aflatoxin (mycotoxins from fungi) costing $75. The new regulations came into effect on November 1st, and so she’s had to stop selling raw milk – she can’t pasteurise it as she doesn’t have a commercial pasteuriser – and she’s had to refer her customers to a powdered goat milk product.

The Doughty’s also have composite cheese curds tested once a month. This is a sample from every batch collected over a week, which she sends to testing company Eurofins. The curd testing costs $105.87 a time. “They test that for coliform mainly and anything else that is ugly such as listeria and salmonella.” The couple both think people are becoming overly bacteria-shy. Brian says historically generations have drunk unpasteurized goat milk and eaten the cheese.

“There’s always those who have got sick from whatever they eat but I don’t think it’s any worse today than what it was when I was a kid. People talk about the Nanny State and this seems to be where we are heading now. We want to protect everything so kids can’t climb trees at school. They’ll make everybody pasteurise milk just in case somebody gets sick. If you recognize that those at risk from raw milk are the young and the old, you manage the risks and put processes in place to do that.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.