A doctor explains why food is the best medicine of all

The best diet for long life and good health is an age old conundrum. Modern insights say it has a lot to do with eating the right drugs.

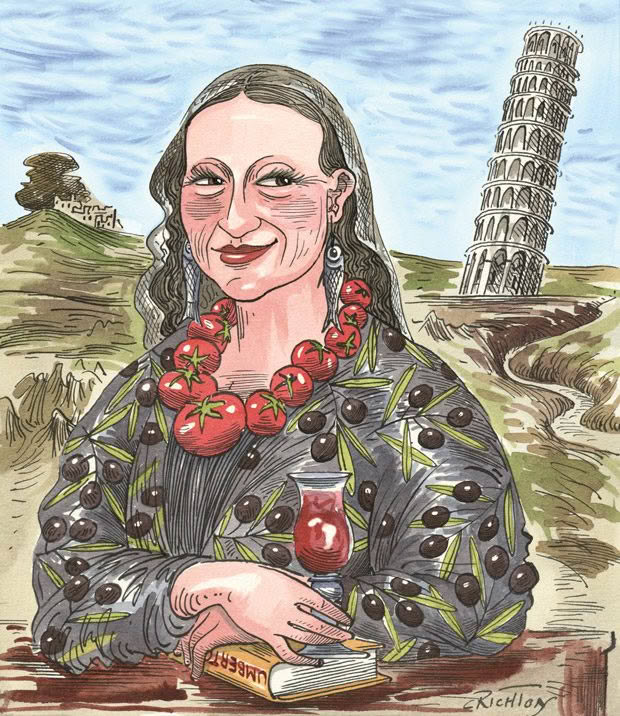

Words: Dr Roderick Mulgan Illustration: Anna Crichton

What makes healthy food healthy? It sounds too obvious to need an answer — like why do apples fall off trees? — until someone notices it isn’t obvious at all and needs explaining. Sir Isaac Newton led us into the higher realms of physics when he noticed the apple issue, and many other useful insights have occurred throughout science because someone asked why. Good eating is no different.

People do not fall over dead if they fuel themselves on hamburgers and fried chicken every day, which stands to reason. We need protein, carbohydrates and fat to get by, with a sprinkling of micronutrients such as vitamins, and even fast food delivers them.

Yet fast food is unhealthy and other styles of eating are dramatically more desirable. The issue, obviously, is not about staying alive day to day but maximizing our life span, and avoiding illness as far as possible along the way. For this, certain diets are known to suit us much better than others.

The best known good-living option is commonly called the Mediterranean diet, which is what the people of Spain, France and Italy eat, or at least what they used to eat before McDonald’s arrived. Tomatoes and eggplants, walnuts and chickpeas, rosemary and sage, all ripened in the long summer and swimming in olive oil. With sardines and judicious measures of red wine.

I simplify, but you know what I mean. There are variations on the theme all over the planet, but the basic principles are consistent. Lots of plants, small amounts of protein, sea-based if possible, and small amounts of plant fat. All eaten more or less as they grew, by which I mean with little processing. Off the tree and into the saucepan. Or the oil press.

Some think it is all about more of the good things, particularly vitamins. Vitamins are known to be vital, so the thinking often goes that more is better. Millions swallow vitamins in pills to max out their intake, yet with certain exceptions, such as vitamin D for some selected people, it isn’t true. Enough is enough when it comes to vitamins and more just means expensive urine.

In some ways, healthy diets succeed because of what they are not. They are not too much animal fat or sugar or salt. All these are present, but in proportion to the whole food, not purified and added with gusto because a food scientist employed by a conglomerate knows you like it. These diets are also full of fibre, which are long chain-like molecules that create the crunch in vegetables. You can’t digest fibre but the bacteria that live in the bowel eat it all day long. Those bacteria are pivotal for your long-term health on many fronts, so it’s necessary to feed them what they like.

These topics could be expanded at length (and in future columns they will be), but there is one more aspect of the right food that is not as well-known as it should be. That is nutraceuticals. The insight is so new we have only had the word about three decades and it means what it sounds like: nutritional drugs.

Many plants have molecules that stir us up. The law courts are full of people who have noticed — as has big pharma, which makes lots of money selling legal plant options such as aspirin and penicillin.

Yet quietly hidden in many food items are the foot soldiers of this botanical brigade. Grape skins have resveratrol. Chocolate has epicatechin. Blueberries have anthocyanins, which makes them purple; chillies have capsaicin, which makes them hot. Onions have quercetin and pomegranates have ellagitannins. Coffee has chlorogenic acids and tomatoes have lycopene.

Numerous more examples permeate the catalogue of plant food. These are nutraceuticals. Nutraceuticals are not nutrition in the traditional sense; they do not feed you. Your body does not need them to function normally, as it does with protein or iron. Nutraceuticals manipulate you. They lower blood pressure. They dial down your immune system so inflammation does not get out of hand. They inhibit tumours, lower cholesterol, and stop platelets sticking together, which inhibits the blood clots behind heart attacks and strokes. They are multipronged fine-tuners and supporters of the better, healthier, longevity-promoting side of your cell and organ functions.

It was epidemiologists who first confirmed the Mediterranean diet was healthy, based on watching people who ate it and comparing them with others who ate differently. Epidemiologists study groups of people to see what aspects of their life and environment do them good or harm. A consistent theme of their craft is that the pattern emerges before the explanation.

The discipline started in 1854 when London authorities removed the handle of the Broad Street water pump because too many people drinking there got cholera, even though official opinion doubted there was any such thing as infectious organisms.

Decades later, in the first half of the 20th century, lung cancer rates were seen to rise, yet the first study that blamed smoking, in 1950, surprised many, including its own author, a smoker, who always thought the culprit was engine fumes. It is the same with eating. The diet gurus have long known what works, and even they are only building on the folk wisdom of the ages. It has taken much longer to work out why that should be.

In large part, it means eat your drugs. The right plants on your plate drug you for good health every bit as skillfully as your GP does and good health lies with getting plenty of them.

MORE HERE

How silent inflammation can affect health outcomes later in life

How silent inflammation can affect health outcomes later in life

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.