A houseboat and a tiny cabin straight out of the Shire

“There are serenading frogs in the pond next to our home and a symphony of birds every dawn and dusk. We have sheep eating the grass around our house — it’s funny to see a bunch of sheep munching happily at the doorstep.”

This jeweller and doctor duo from Poland might be the best ambassadors for tiny living.

Words: Nicole Barratt Photos: Daniel Allen

Mike Andre couldn’t have picked a more fitting career for tiny-home living. Pliers, silver granules and black sand vials sit neatly on a desk in the jewellery artist’s six-metre-by-2.2-metre Blenheim home. “A typical jeweller’s desk is only a metre wide or less; you could squeeze one under a staircase like in Harry Potter’s bedroom.” The mini atelier’s location is unique: parked on a hill covered in ripening Blenheim grapes.

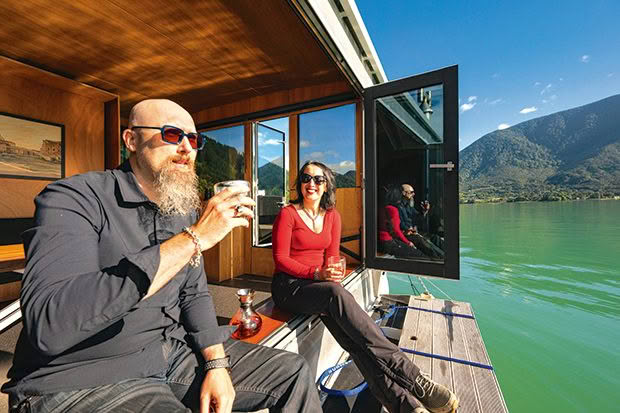

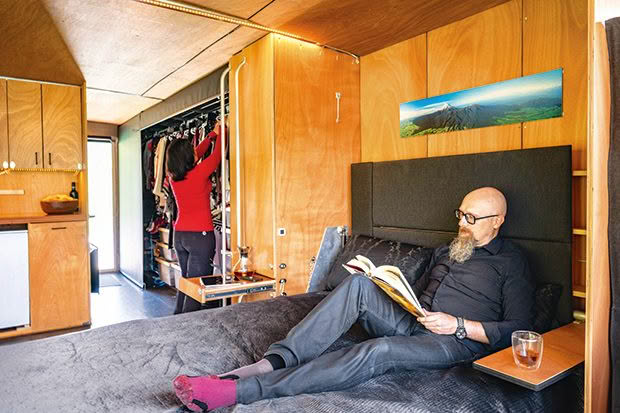

Mike is a tiny-living and tiny-working expert. His original home and studio — a self-built houseboat — floats in Havelock Marina, 30 minutes down the road. Polish-born Mike and his wife Margaret split their time between both, a far cry from the towering apartment blocks they grew up in.

The surrounding vineyards are usually quiet but occasionally bustle with workers cutting, spraying, netting and harvesting. “It’s part of living in the country, and we love it.”

“We lived in 10- to 14-floor post-communist concrete monstrosities,” says Mike. “When you’re a kid, you don’t know any better, and it’s just normal.” Neither felt Poland was their forever home; both were out of place as teenagers. “Our natures have never really been Polish. Poland is still recovering from its history; you see it in the mentality. People are a little more closed off — until you sit down and start drinking vodka with them.”

Mike’s workspace has a view of the countryside. “Most jewellers have a bench next to a wall and don’t see outside at all. We lost space for a couch because of my bench, but not even Margaret wants me to change it. It’s perfect.”

The couple met in 2001 as university students in Poznań; Mike was studying law and Margaret medicine. “I saw her at a tram station. I was going to the library; she was on a first date. I’ve always just approached people I think look interesting, so I picked the only flower I could find off a bush and walked up and gave it to her.” She cleared her schedule for a second date later that day.

It was film director and screenwriter Peter Jackson who first planted visions of towering mountains and tranquil waters in the couple’s heads. “Watching The Lord of The Rings was a transformative experience for us,” says Mike.

The only extra storage the pair have is a small metal shed behind their tiny home. “We use it to keep our two electric bikes out of the elements and store my construction tools. We wouldn’t need a shed if it weren’t for the bikes. I keep my paragliding wings inside our tiny to ensure no mice chew through them.”

“We absorbed the films like documentaries and knew what we wanted — not so much the orcs, but to find The Shire. We knew we didn’t want to be in an apartment or surrounded by fences.”

First was a five-year stint in Scotland and Wales while Margaret completed her medical training. “Living there was a breath of relief for us. We wanted something different culture-wise, and we got it. We’d chase the sun on our days off, driving up hills in the countryside and looking for pockets where it wasn’t raining.”

That unrelenting rain eventually pushed the pair to book one-way tickets to New Zealand in 2011 and seek their Shire dream. A tiny home and houseboat were never part of the plan; the steadily approaching end of a lease on their Lower Hutt rental led the couple to the water. “We didn’t want a huge mortgage for a house. The thought felt like an anchor on us. I’d always liked building, so I’d been looking at houseboats as an alternative option.”

Mike and Margaret regularly adventure on their boat in the Sounds in summer. “Our current favourite is Kenepuru Sound, with great mooring spots near Portage.”

No stranger to the ocean, Mike learned to sail in the Adriatic Sea as a child — his parents were keen sailors. “I think life gently nudged me back towards the sea. Margaret didn’t grow up around water, and I wanted the boat to succeed. I knew a houseboat would be a gentler introduction to boating than moving us onto a yacht with bunks.”

They spent $100,000 on an old aluminium dive boat, the shell of their new home. “We only had four months left on our lease. I promised Margaret that our house on water would have walls, insulation, water and electricity by the time we had to move out, but realistically, that was it.”

Mike designed the houseboat so the couple could embrace the outdoors. “The French windows are standard residential ones that were marinised. All the windows on the boat are double-glazed and have anti-sun treatment to keep the inside cool.”

The build wasn’t easy. They lived on the boat for two years while Mike clocked up more than 2000 building hours. He had a welding course under his belt and some construction skills, but he researched as he went on YouTube.

“I’ve never been afraid of learning new things; everyone is capable of it. But I wouldn’t recommend moving onto a construction site while you build.”

The initial set-up featured Styrofoam-insulated walls, a mattress and a mini fridge — plus a litter box for the pair’s cats (Lady Large and Sir Humphrey). “It wasn’t ideal, but we didn’t have a choice. We made it work.”

A harbour view in Wellington’s Seaview Marina made the hardships worthwhile. Mike says that downsizing from a house to live on a 13.5-metre-by-four-metre boat was challenging but liberating. “It’s hard to part with stuff, but once you let go of things, you realise how much we fill our homes just because the space is there.”

The cats took some time acclimatising to the water but eventually developed their sea legs (a fishing net was bought to scoop Lady Large, who slipped off the boat’s edge more than once, from the water).

The couple say they’ve met some interesting people in marinas. “Marinas can feel a little like those United States retirement homes where everyone plays golf — we all have this shared interest: we all love boats here”; they transported their houseboat from Wellington to the Marlborough Sounds via the Interislander ferry. “It was definitely easier than coming across the Cook Strait.”

Mike worked remotely in IT up until the move, often on calls overseas until 2am. “I was building software for people to work remotely. We sold the company and lost money on it right before the pandemic hit — when working from home became mainstream — so my timing wasn’t perfect,” he says.

“Working with my hands has always been what I love, and jewellery making is an extension of that. Margaret encouraged me to change my hobby into a business, and it was a win-win: either it would take off, or she would end up with a lot of lovely jewellery.”

He says that learning to create jewellery is like building — learning takes time, but the rewards are tangible. “Ideas come much faster than I can keep up with. The challenging part is developing relationships with galleries and figuring out what sells in a New Zealand market.”

After their initial challenges, the couple spent three “idyllic” years moored at the end of a dock in Wellington’s harbour but still dreamed of finding their Shire equivalent. Marlborough Sounds was the solution. The only spanner in the works: no liveaboards allowed at Havelock Marina, a spot the pair had hand-picked for their houseboat.

“We found out we could only spend seven nights a month sleeping in the marina, so we needed another home on land.

It wasn’t a huge problem. We thought, ‘Worst comes to worst, we can just lift the boat out and have a Noah’s Ark on land.’”

Experts at downsizing, a tiny home was the natural solution (no Noah’s Ark needed). A colleague of Margaret’s happened to be selling her home on wheels, parked in a Blenheim vineyard. “It was a little too small. We knew we’d need to sacrifice the lounge space for my workspace, but the location sold us. We could continue leasing the land and were surrounded by mountains and vineyards with no fences in sight.”

Tiny living fosters a deep connection with the outdoors, Mike says. And it brings a sense of peace. “Having smaller spaces means you exist with the elements. It’s not like you’re going into a giant castle at the end of the day and barricading yourself up. We’re watching nature all the time.”

The tiny home created the ideal base for Margaret, now a doctor at Blenheim Hospital, who is often on-call at night. For Mike, he couldn’t have dreamed up a better work view. “We’ve made sacrifices living small and doing things a bit differently, but we’ve always said that life isn’t a rehearsal. We never want to feel like we need to escape our life, and if that means living slightly outside of the mainstream, it’s worth it.”

He admits there is something rather Lord of The Rings-esque about melting metals and tapping away at precious rocks surrounded by mountains. But if anyone ever compared him or his life to that of a hobbit, he wouldn’t mind at all.

THE HOUSE (BOAT) THAT MIKE BUILT

Mike learned plenty while constructing his houseboat:

● A build will take longer than expected. “Estimate the best you can do for how long each task will take, then multiply it by five. Nothing is square on a boat, access is problematic, and something is always in the way. The work is not difficult, but the basic knowledge you must absorb is extensive. YouTube to the rescue.”

● Repairs or rebuilding are far more straightforward with a self-built project. “Building the houseboat was thousands of hours of work, but by teaching yourself, you know how to fix any issue that comes up.”

● Mistakes are a given. “You will make mistakes, no biggie. I call the issues ‘character’, and our houseboat has a lot of character. Builders have a saying that one should build at least two houses before building one’s own.”

● There are no rewards quite like building. “The process is extremely rewarding, and the final result is tailored to your needs like no purchased product could ever be.”

ALL THAT GLITTERS

Mike created his first jewellery piece — for Margaret 20 years ago — a whittled wooden heart. “She still wears it on a chain around her neck. It’s her favourite.” He describes his style as like his interior style — mid-century/Scandi-inspired with a modern twist. He doesn’t use animal materials, and he only works in silver. “Like blood diamonds, gold has a lot of problems with its sourcing. I’m going a little against the mainstream here in New Zealand as many people love gold; it’s more of a European style.” Mike often listens to books or lectures as he creates.

“I have time now for what I love most: learning while working with my hands. I’ve just finished a podcast of great historical lectures from a course at Yale University about the making of modern Ukraine.” (tinyurl.com/56a3yzj8)

He has stockists in Auckland, Wellington, Nelson, Blenheim Christchurch and Queenstown. “The change from IT is huge, but doing something physical and tangible has been transformative.

I love it when people contact me on Instagram or over email, so I don’t feel too much like a hermit dwarf forging treasures under the mountain.” @mikeandrejewellery / andre.co.nz

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.