A green-thumbed couple transformed their dry block into a perennial food forest and bountiful permaculture farm

Jo and Aaron Duff.

Twelve years ago, an enterprising couple started creating a permaculture food forest and perennial farm on a dusty, bare block in a dry Hawke’s Bay valley. Today, it’s unrecognisable.

Words & images: Vivienne Haldane

Who: Jo, Aaron, Anna (11) and Eliza (9) Duff, Kahikatea Farm

Land: 6ha (16 acres)

Where: Poukawa Valley, 16km south-west of Hastings

What: off-grid, certified organic nursery selling 300 varieties of trees and plants, permaculture farm, food forest

When Jo Duff wants a snack, she can choose from some of the most unusual edible plants you can grow. One is the succulent, salty, New Zealand native horokaka (ice plant, Disphyma australe). However, there’s always the risk of being startled by lurking frogs when they hop out of the plants growing in her certified organic nursery.

She can pick leaves of strawberry spinach (Chenopodium foliosm) and false valerian (Centranthus ruber), handfuls of litchi tomatoes (Solanum sisymbriifolium), and she’s often munching on aquilegia flowers.

READ MORE: Practicing the principles of permaculture at Kahikatea farm

They’re just a few of the hundreds of plants, mostly perennials, that she grows on Kahikatea Farm. The property features 10 swales, five ponds, timber and firewood lots, just over a hectare of developing wetlands, and a huge orchard and food forest.

But it was a bare block when Jo and Aaron bought it in 2005 at the beginning of their permaculture journey. Since then, they’ve transformed the landscape, started a nursery business, had daughters Anna and Eliza, and built an energy-efficient, 60m² off-grid home. It has a composting toilet, woodstove, greywater irrigation, and walls decorated with homemade paint and plaster. From the verandah, you look out over the farm through a curtain of rampant roses.

“Kahikatea Farm is getting a character of its own, and that fills me with joy,” says Jo. “I feel as if we’re now joining the dots. Sometimes I drool over pictures of other permaculture sites, then look outside and go, ‘oh yeah, actually ours is coming along nicely!'”

Jo walking through the open centre of the food forest (it’s yet to be planted).

She’s learned a lot working to turn dry hills and pasture into a forest in a microclimate where the average rainfall is 650mm, one of the lowest in NZ. “I’d never grown anything in this climate and didn’t know much about the area.”

The last year has been one of the driest since they started, a mere 537mm. From November to March, they got just 75mm. “On the one hand, I look out at the trees that have grown quite happily, and wonder ‘how are you doing that?’

“On the other, we did a lot of planting last winter, and we’ve lost half of them, and we’ve never had a loss like that before. It’s things like Italian alders which we wouldn’t expect to lose – we’re not planting things that really need water, but plants to try and build the soil so we can then plant more productive trees.

A bean archway with flowering breadseed poppies on the right.

“But even those support species are struggling. That’s been a real challenge.”

The couple has also reached the limit of their solar array. It powers the house and nursery, so there’s nothing left for irrigation. “We’ve got access to water, but we can’t pump it with the solar power, so we’ve had to run a generator. We’re looking at our options for how we expand it.”

The permaculture passion project

UK-born Jo describes herself as an outside person who needs to connect to nature. “I’ve always wanted to care for the environment and was into sustainability from an early age.”

The certified organic nursery now grows perennial edible plants.

She and Aaron moved to Hawke’s Bay after travelling and working in other parts of the world. During that time, Jo studied permaculture in Australia, then in Taranaki. Their block used to be part of a sheep and cattle farm, a mix of flat and contoured land, with a dam. While the couple always had ambitious plans to turn it into a permaculture-based food forest, they didn’t rush into planting.

Instead, they spent three years observing their blank canvas to see where the prevailing winds came from, the direction of the sun, wet areas, and runoff before they started planting in 2008. Working with, rather than against nature is an important principle in permaculture. Everything the couple has planted has one, but usually multiple purposes.

The first plantings included:

• an annual-based food garden around the house;

• a perennial food forest to feed their family, attract insects and other biodiversity, and build soil;

• firewood trees which also act as shelter;

• green crops to use as mulch;

• trees to use for animal fodder.

The first big project was a shelterbelt of pines to protect them from strong southerlies. An edible hedgerow went in as shelter from the north-west winds. It includes tough species such as hawthorn, hazel, cherry plums, crabapples, silverberries, koromiko, and pittosporums.

The pond in the middle of the food forest.

It protects the main edible crops, including apples, pears, plums, peaches, and citrus. Planted among them are nitrogen-fixing trees such as tree lucerne (tagasaste), acacia, and Italian alder. These have been heavily pruned over the years to provide mulch, build soil, and allow in light.

They gradually added other varieties, developing their block into a food forest. There’s an eclectic mix of trees, including persimmons, loquats, American pawpaws, dogwoods, Aronia melanocarpa, and Canadian serviceberries (Amelanchier canadensis).

“The food forest area is developing nicely,” says Jo. “The trees are becoming mature, and we’re retrofitting some of the understoreys with salad herbs such as lemon sorrel and salad burnet, and biomass plants such as tree lupins and globe artichokes. It’s developing a life of its own with lots of self-seeding.”

- Looking up to the house through globe artichokes and nectarine trees.

- A ‘chook dome’ to house birds so they clear an area of grass and weeds.

- Jo places hoops over a tree to hold frost cloth.

The home vegetable garden has moved. It was originally around the house (permaculture zone 1) but is now beside the nursery and inside its polytunnels.

“Since I’ve become so busy with the nursery, it has become our zone 1,” says Jo. “I’m there more often, and it gets watered better there than if we had it around the house.”

One of the limiting factors at the farm is the solar power system, which was initially set up to power just the house. “We’re maxed out on what we can irrigate at the nursery so we can’t expand the nursery or any areas of planting – it’s the next item on our list to decide on.”

Why they’ve (finally) decided to get livestock

Two hectares of the farm is part of a new agro-silvo-pastoralism project, a mix of trees, small-scale crops, and pasture. It will mean the Duffs can run cattle for the first time. Jo says she’s excited to get livestock now she understands how holistic grazing methods can improve the soil.

“Cattle are an element that’s been missing and are something I’ve wanted for ages. There’s something magic about them.”

She and Aaron haven’t had livestock before, for several reasons:

• to protect the trees while they were young;

• because Jo was working off-farm;

• the cost of setting up fencing;

• the expense and difficulty of setting up drinking water systems (much harder when you’re off the grid).

Jo has been planting areas of fodder trees, including alder, tagasaste, sycamore, browsing rows of feijoa, hebe, flax, and random spare trees from the nursery.

“The trees are basically vertical grass,” says Jo. “Instead of having food on the ground, we’ve got it in the air’.”

The ideas that did and didn’t work

Jo and Aaron’s original plan was to run a community-supported agriculture scheme. It morphed into a nursery growing annual vegetable seedlings, perennials, and culinary and medicinal herbs, which they sold at local markets and health food stores. Jo also taught horticulture part-time at the Eastern Institute of Technology.

But after four years it all became too much.

“We had a major rethink and stopped doing annual vegetable seedlings – it was a lot of work for not much money,” says Jo. “It also didn’t fit with our permaculture focus. Instead, we focused on the perennials: edible and medicinal herbs, dye plants, nitrogen fixers, bee plants and other companions, and unusual edible trees and shrubs.”

- The food forest trees are mostly perennials, providing fruit and nuts, encouraging biodiversity, and improving the soil.

- Jo and Aaron employ part-time workers in their certified organic nursery. It’s far more productive than using wwoofers as they did for 10 years.

Now 99 percent of their plants are sold via their website, the rest at Cornucopia Organic Shop in Hastings. In 2016 they built a nursery area for plant production and freight preparation. Jo also runs permaculture courses and farm tours. “This new setup works much better for us,” she says.

Employing local workers on the farm has boosted their productivity and enabled the nursery and farm to become a profitable business.

“We had wwoofers for 10 years,” says Jo. “But that way of doing things lacked consistency.”

Despite the many challenges, Jo and Aaron say they wouldn’t change a thing. In the last year, they’ve enlarged the pond in the food forest, put in another one near the nursery, and created a new swale across their biggest paddock. They plan to develop herb gardens for demonstration purposes and to increase their plant stock.

“Each year we’re doing better,” says Jo. “We love it here. There’s nothing else we’d rather be doing, and nowhere else we’d rather be.”

BEFORE & AFTER: THE SWALES

Swales (shallow ditches) were dug on contours to retain rainwater. Jo and Aaron planted on their downhill side so trees and plants could use the much-needed deep-down moisture in summer. The swales now merge with the trees and are hard to see.

“When you go down into one of the hollows lined with shady trees, it’s a lovely microclimate,” says Jo. “We also get an amazing frog chorus in the evening.” The problem is it’s impossible to know exactly what impact they’ve had, says Jo. “…because you don’t know what it would have been like if you hadn’t put them in.”

Before: 2018.

She can say they’ve all worked differently. The biggest one holds water almost year-round and has become its own microclimate, with naturalised raupo, poplar, and willow. The longest swale (pictured here under construction) has functioned best, probably because it was the one they planted most intensively.

“It holds water for about three days in a heavy rainfall event and then it soaks in, so that’s what (permaculture guru) Geoff Lawton describes as the ultimate aim (of swales).

A digger carving the first swale into the side of a hill in what is now the food forest.

“The downside is the banks of the berm are quite steep, so it’s been quite hard to get ground covers going, and grass always comes back. We’ve left that now to concentrate on other areas where we’ve gained traction with ground covers.

“I don’t think you could do very much differently (except) probably make the (trench) a bit wider and the berm a bit wider.”

One swale has been a lesson in what not to do.

“It was probably a mistake,” says Jo. “The hill was too steep – you need to look at how steep your hills are, and really it shouldn’t have been more than a 15 percent incline.

After: 2019. The newest swale is just a year old, planted with quince and understorey plants such as comfrey and borage.

“Terraces or a series of smaller swales would have been probably ok, but one big one caused erosion. We’ve ended up losing planting space, whereas you’d gain more plantable land from doing smaller swales.

“Where it’s steeper, we’ve now gone back and terraced it, and that’s working.”

Jo says the swales have helped to keep trees alive during dry summers, but also, more surprisingly, through wet winters. “What they do on clay soils is lift the tree roots out of that claggy wetness in winter,” she says. “It’s not just about storing water for summer, it’s about lifting the roots out of what would actually kill them in a wet winter.”

What is a swale?

A swale is a flat-bottomed ditch cut into a shallow to moderate slope. A slope up to 17° is the oft-quoted maximum angle, but Jo says she now believes less than 15° is better, to avoid erosion.

A mound of soil (the berm) sits on the downhill side, and plant roots hold it in place. Water coming down the hill stops when it enters the trench, then slowly dissipates through the berm. In drier climates, the berm is a prime growing space for shrubs and trees. However, Jo has found in their arid climate some trees love to grow in the trench as well.

WHAT IS PERMACULTURE?

Permaculture – permanent agriculture – is designed to be a radical approach to food production, water, energy, and pollution.

“Permaculture is a design system for creating sustainable human environments,” writes co-creator Bill Mollison in the book Introduction to Permaculture. “On one level, it deals with plants, animals, buildings and infrastructure (water, energy, communication). However, permaculture is not about these elements themselves, but rather about the relationships we can create between them by the way we place them in the landscape.”

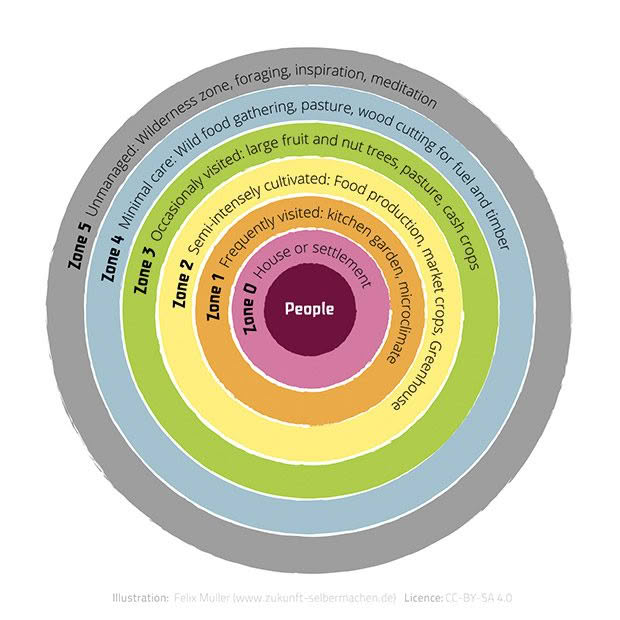

The six Permaculture Zones (0-5): Zones are a way of creating an energy-efficient garden or farm by placing the highest use areas closest to you. Think of it as concentric circles radiating out from your house.

Mollison says permaculture encourages a different mindset to conventional culture:

• it’s information and imagination intensive;

• you work with nature rather than against it;

• the problem is the solution, ie you don’t have a slug problem, you have a duck deficiency;

• make the least change for the greatest possible effect;

• the yield of a system is theoretically unlimited (or only limited by the imagination and information of the designer);

• everything gardens (or modifies its environment).

Fellow co-creator David Holmgren has since updated the principles to include:

• observe and interact;

• catch and store energy;

• use and value renewable resources and services;

• produce no waste;

• use small, slow solutions;

• creatively use and respond to change.

4 STEPS TO CREATING NEW SOIL

Jo has four separate strategies for creating a new productive garden bed:

• sheet mulching with layers of cardboard, manure, straw and wood chips;

• growing biomass plants to ‘chop and drop’ as mulch (see page 29);

• lots of compost;

• using chickens.

A new garden bed, edged in windfall gum, is layers of mulch, biomass plants, and compost.

“The strategy we use depends on the time of year, available labour and time, and the existing ground cover. For example, couch grass can’t be killed off completely with sheet mulching but is easier to control by planting more dominant species into it, even if these are later cut out and replaced by the desired species.”

What are biomass plants?

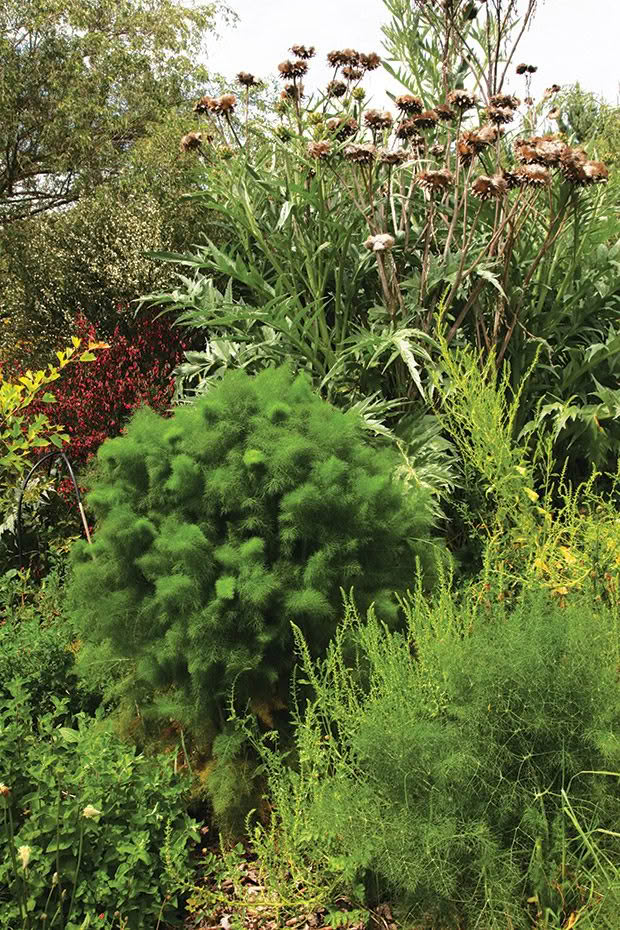

Jo’s favourite biomass plants in her food forest include globe artichokes, wild fennel, and silverberries. All provide large quantities of foliage, which is chopped down to provide mulch. As it decomposes, it also helps to nourish the soil.

These are trees and herbs that have lots of large leaves. They also grow (and regrow) fast, so they can be cut down repeatedly. Jo grows a range of biomass plants in the food forest, including several types of artichoke, wild fennel, and silverberry (Elaeagnus x ebbingei).

MORE HERE:

10 unusual edible perennials grown at a permaculture farm near Hastings

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.