A gardening legend’s third horticulture venture is a triumph

“You have to be young and stupid to start a garden, and it’s best not to be not old and stupid as well,” says Gordon Collier, sitting beneath a Dutch hoe, a treasured relic dating to 1869 from nearby Westoe Garden, and a plaque reading, “Old gardeners never die, they merely spade away.”

Pushing close to four score and 10 isn’t deterring this horticultural legend from developing a third significant garden. He’s only slightly impacted by bedding in a new hip and is having the time of his life on his most exciting project yet.

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Tessa Chrisp

Gordon Collier thinks being described as “perverse” is a compliment. It has been his life’s work to avoid the well-trodden path unless it should lead to a glade of naturalistic planting. Then, maybe, he’d take a wander along it.

Similarly, he’s never been one for rose-tinted spectacles unless they should be required to enjoy a beautiful rose such as ‘Shot Silk’, perhaps. This beauty clambered happily up a wall behind a young Gordon’s strawberry and pansy patch at a small primary school called Bell’s Junction, inland from Taihape. He was in fierce competition with his only classmate, Cousin Sylvia, to win the coveted prize for best vegetable garden.

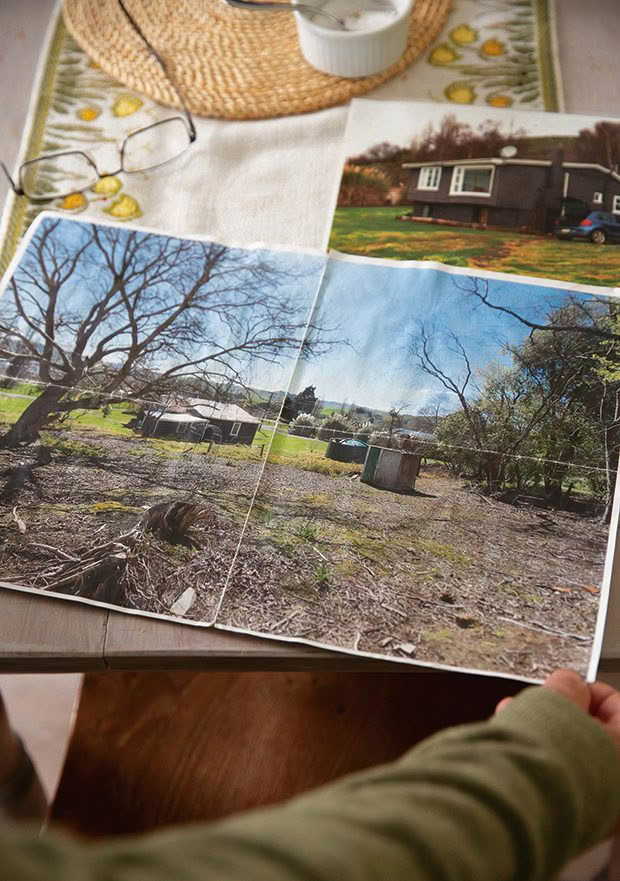

A tangle of woodland planting carpets the gently rising slope behind Gordon’s Taihape home.

This independent nature flowered throughout his childhood on the family farm, blooming nicely the day he visited his grandmother, Catherine Ramson, as an 18-year-old school-leaver to tell her of his plans to enrol at Massey Agricultural College in Palmerston North. “I am going to do a two-year diploma in horticulture,” he proudly announced.

“What is there to learn about gardening?” was the tart response of an Irishwoman also skilled in straight-talking. Seventy years on, he is still musing over an adequate reply. In the foreword to his latest (and fifth) book, Gordon Collier’s 3 Gardens, he’s having a shot at it. “Dear Granny,” he writes, “There’s no doubting your astonishment. Sons of farming families in those long-gone days were not expected to leap from the family fold and go gardening.”

Girls did the gardening back then; it was perceived as mostly about growing flowers. So, it wasn’t always easy being a boy doing it. Gordon wasn’t that interested in flowers. He quite liked them but was as much interested in design and in creating gardens.

“I knew it was unusual for men in rural New Zealand to be gardening. Not that people made me feel uncomfortable. I felt that way. It was highly respected for men to be gardening in England and the United States but not New Zealand at that time.”

Gordon is a fan of Marton-based sculptor Stueart Welch, who created a gate of corten steel items vaguely similar to garden tools and the tall corten steel pole alongside the gate sculpture.

Not uncomfortable enough to send Gordon along a more ordinary path, however. Following graduation, his first job took him to Tūpare near New Plymouth, a garden he still regards as a favourite. The Matthews family developed gardens around their arts and crafts-style home (designed by leading New Zealand architect of the 1930s, James Chapman-Taylor) in a multitude of intertwined areas, harnessing the great gardening traditions of England. Tūpare, now owned and managed by the Taranaki Regional Council, has lived in Gordon’s memory and heart ever since. His year’s apprenticeship to Sir Russell Matthews in that horticultural paradise stood him in good stead for what was to come — a distinguished career in horticulture, achieving international recognition.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves, Granny.

Off Gordon went to do his OE in Europe; based in London’s Earls Court, being a gardener, driving a little Morris van, and working with Alfred, his workmate from Sierra Leone (“he as black as midnight and me as white as snow; quite the odd couple and getting on famously”). Gordon had the time of his life tending gardens, tiny (window boxes) and massive, and with as interesting owners as Douglas Bader (the British war hero who lost his legs in an air crash).

The red forest pansy (Cercis canadensis), a tamarisk and very old lilacs form the northern boundary of the gravel garden surrounding a 200-year-old French urn purchased 40 years ago from Richard Matthews Antiques in Auckland’s Remuera. “I wish I could have afforded its matching partner, and I’ve wondered since where it went.” The base of the urn is planted in bidibid (Acaena anserinifolia). “Many people think bidibids are weeds, but I have many weeds in my garden. I love to see what pops up in the gravel. I pinched the yellow daisy from a garden on the north shore of Lake Taupō — a found object”.

He attended the fortnightly Royal Horticultural Society shows (mini Chelsea Flower Shows). He formed a friendship with famous British gardener Beth Chatto, who stirred his interest in woodland and gravel gardens. And he struck up an acquaintance with Mrs Desmond Underwood. Mrs Desmond Underwood specialised in silver and grey plants.

And Gordon scooted all over Europe, soaking up the atmosphere of its most extraordinary gardens. The Alhambra courtyard and fountain gardens in Spain provided a profound experience. There, among the palaces and fortresses, with their exquisite Moorish arches, fountains and ponds, he found the inspiration for his second garden, Anacapri, in Taupō, which came into being many, many decades later.

Mrs Desmond Underwood’s influence these many decades later is still alive and much progressed, of course, in front of Gordon’s latest home, modestly known as The White House. The house commands an enviable position with a gently rising hill giving shelter to the south, an expansive northern outlook across Taihape, a kilometre to the north, with Gordon’s maunga, Ruapehu, sitting serenely to the west. In front of the house — greeting visitors — is a silver and grey garden; a lovely tangle of white and silver plants reflecting light from the house and spilling across the gravel.

These small concretions (smaller versions of the famous Moeraki Boulders) are a valued find from a rafting trip on the nearby Rangitaiki River. They are arranged on top of a section of an old strainer post he found and fancied. Ajuga, flax and geranium surround his collection.

Gordon’s departure from his OE in Europe on the Ruahine was a reluctant one. He brought home a box of plants, including hostas, rodgersias, lysichiton and the Stachys ‘Silver Carpet’ now found New Zealand-wide, including in his latest garden. He returned to his family’s sheep farm and began work as a shepherd to support the family he and his wife Annette had begun. On his afternoons off, he set out to create beauty in a boggy corner of his parents’ garden. Looking back, he thinks he was mad to take on a piece of claypan land on a steep slope. “Those first four years when I went back to the farm were difficult, very difficult. I had to adapt to doing things, and I am not a very practical person naturally.”

The result, after 30 years, was Titoki Point, a wonderland attracting people numerous and distinguished. During the 1980s, it drew thousands of visitors a year and became New Zealand’s most well-known garden of its day.

In the early 2000s, Annette and Gordon moved to Taupō and set out again to create a garden. No muddy pond nor steep gullies to beautify here but a new sub-division of flat land near Lake Taupō at Five Mile Bay. Anacapri, as Gordon called his second significant garden, was informed to at least some extent by his memories of the Alhambra Gardens and earned its creator the highest possible accolade (of six stars) from the New Zealand Garden Trust.

“Different, very different, and the most exciting garden I’ve ever created and not in the least fashionable ,” Gordon says of his current project. “I’ve been around long enough to ignore the rules. What I am doing here is unlike anything I have done before.” The wild woodland garden behind his house includes an 80-year-old walnut tree, a trellis arch and hundreds of different plants treasured by the original gardener, Iris Seal. “I couldn’t destroy someone else’s garden, so even the plants I don’t like, I look after.” Yellow kniphofia (red hot pokers), euphorbias, alstroemeria, poppies, lilac, snow-in-summer, snowdrops, granny bonnets and hundreds of violas rule a riotous display. Hellebores — dozens of them — are a winter favourite.

Again, with reluctance and following Annette’s death eight years ago, Gordon felt the need to move again. Fetching up in Taihape completes a circle of returning almost to the place of his birth and right into the bosom of his numerous family and friends. He knows the land and its seasons. His two sisters live locally, as do many nieces and nephews (he and Annette married the other’s sibling, as did his parents so there are plenty of close relatives). And, very crucially, his daughter Meredith and her family live at nearby Ruanui Station.

Here, Gordon fully indulges his love of “found objects”; a pole, a pipe and a salt-lick pot, for example, star in his front garden. They are all proudly and carefully placed in the gravel in harmony with Gordon’s desire to honour things of the place. It makes him laugh like a drain that his sister, also a Taihape local, detests the corten-steel sculpture that is paramount in the most prominent area of his new garden.

“It’s not everyone’s cup of tea,” he says wickedly, relishing doing things his way even to the dismay of others. “She lived in Vienna for years, and it is not the sort of thing you’d see in Vienna, is it?”

Gordon is colour blind, but he groups similarly hued plants, as in this vista showcasing the red foliage of native flaxes and grasses.

He’s having tremendous fun and going to town on this theme of found objects. One day, while visiting his niece on the other side of town, he remarked on a fine round timber pole lying outside her office at the sawmill owned by her family. She realised Gordon fancied it, and one day it turned up at his garden. He couldn’t be happier — or naughtier.

“One lady visitor, a retired psychiatrist, remarked on the pole. I told her it was my last erection, and she told me I had delusions of grandeur. That certainty made the garden group visitors laugh,” says Gordon, laughing almost as loudly as when telling how he tied a bunch of bananas on a banana palm sheltered in a glassed-in corner. The only person taken in by the ruse was a nameless member of his close family. He really is a bad boy sometimes, and sometimes bad boys aren’t believed. He says he has just picked his first tangelos; truly, he swears they didn’t come from New World in Taihape. “They are my skite moment, those tangelos, grown in Taihape. Who can blame me?

The original house was built by the Seals in 1954. It appealed to Gordon for its elevated northerly outlook over his childhood town of Taihape.

“Gardens, unlike other works of art such as paintings, are not static. Gardens are never finished, never perfect. Design is important, but I don’t want mine to look like a dentist’s waiting room, so I keep it loose.

“Have I ever had a ‘Wow, I cracked it moment?’ Yeah, I cracked it with the pond at Titoki Point. I probably didn’t know it at the time, but now when I look back at the photos, I think that was an ‘I cracked it’ moment.”

As he potters in his latest woodland, he wonders what Granny would make of his long career. Was she a good judge, anyway? “No, she didn’t know the first thing about gardening. She was married to a minister and never gardened in her life.”

A POTTED HISTORY OF GORDON COLLIER

Juvenile lancewoods pop up in the woodland garden, where Gordon encourages their prehistoric foliage as a contrast to variegated plants.

“Few have advanced the art of gardening in this country as much as Gordon,” says Jack Hobbs, himself something of a hero of the horticulture world and manager of the Auckland Botanic Gardens. Here are some of Gordon’s achievements:

* Royal New Zealand Horticultural Society — fellow

* NZ Garden Trust — founding member and inaugural judge

* International Dendrology Society — North Island chair

* Eastwoodhill, Pukeiti Rhododendron Trust, Government House (Wellington and Auckland gardens), Tūpare Garden — advisor and trustee

* New Zealand Order of Merit — awarded in 2006

* Gardens writer and editor — NZ House & Garden gardens editor 1997-2005; NZ Life & Leisure contributing editor

* Tour leader to some of the world’s greatest gardens and most far-flung places, including the Chatham Islands and Mongolia

* Four published books, with his fifth due in March 2023

* Significant lectures — three Longwood lectures at Longwood Garden in Philadelphia

GORDON’S THREE GARDENS

He likes the glimpse of sheep beneath the silver birch and above the white and green hydrangeas.

1. Titoki Point (0.8 hectares), 20 kilometres from Taihape, woodland and pond, was one of New Zealand’s leading gardens throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

2. Anacapri (less than 0.6 hectares) in a 2000s subdivision on the eastern shores of Lake Taupō, a nod to Alhambra with water and fountains, paths and points of interest. “The garden was obliterated overnight after the property was sold.”

3. The White House (0.8 hectares) — with a gravel garden, a dry bank, a silver-grey garden and woodland.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.