A beginner’s guide to breeding your dream sheep

A healthy, hardy, delicious flock comes down to one key choice.

Words: Sheryn Dean

Block owner Hayley Parsons is so passionate about wool, her goal is to carpet her home using homegrown fleece. She and husband Chris have teamed up with his sheep farming brother James and wife Janine to educate people with small flocks and sell them quality sheep.

James and Janine Parsons run Ashgrove, a sheep stud just north of Dargaville. James has been farming all his life and is an expert advisor to commercial farmers in Northland. Hayley draws on her brother-in-law’s expertise and uses it to help small flock owners, typically on lifestyle blocks.

Each February, suitable rams and ewes are brought from Ashgrove to their 9ha (22 acre) block in south-west Auckland. They run an education day and auction, saving buyers the hassle of travelling hours north to Dargaville.

- James and Janine Parsons with their farm dogs on Ashgrove Stud.

- The centrepiece is 111-year-old Huntly House, their 380m², native timber, two-storeyed mansion, originally from Palmerston North. The couple have meticulously restored it on its new site overlooking the Manukau Harbour. Chandeliers hang above what was once a mechanics pit, and a modern kitchen accommodates caterers who feed guests.

- From L-R Hayley, Chris, Janine, and James.

- Hayley’s goal with the auction is to show every benefit of sheep, including wool, meat, and even manure.

But it’s not like a commercial sheep sale with bewildering statistics and farmers paying thousands of dollars with a twitch of their nose. James says their goal is to share information on breeding traits and help people buy the sheep that suit their needs.

“There’s no such thing as the perfect sheep,” says James. “It’s about selecting (sheep) for the traits you want.”

Each year, Hayley and James carefully craft an easy-to-understand catalogue aimed at small flock owners. She converts lines of complicated statistics into symbols that describe the top traits of each ram and its ranking on a national scale.

“I simplified it so buyers could see at a glance what traits the breed possessed and how that ram ranked nationally.”

Hayley says their auction day is a way to diversify and utilise their block. They also regularly host Airbnb guests in self-contained units.

For Hayley, the day is all about demonstrating the benefits of sheep. James brings his farm dogs and puts on a demonstration of how a dog works sheep. Spinners and weavers show what can be done with a fleece. Their children sell sheep manure by the bag.

“We want to use the day (of the auction) to demonstrate the whole cycle of sheep to jersey. I envisage it as being a hub of knowledge with a crutching demonstration, and Ashgrove lamb on the barbecue.

“It’s a place where you can ask all those questions of people like James and Chris who have worked with sheep and know the answers, but also know how to come at it from the perspective of someone with a small flock.”

WHY MATERNAL VS TERMINAL IS IMPORTANT

There are two main types of sheep breeds in NZ – maternal and terminal.

“Maternal breeds, like Coopworth, Romney, and Perendale, are selected for their mothering capacity,” says James. “They have high fertility, are good mothers, produce ample milk, usually have higher disease resistance, and have a good white wool clip.

“Terminal breeds, like Suffolk, Texel, and Dorset, have bigger carcasses and are selected for growth, but not mothering ability, disease resistance, and longevity.”

The bigger, meatier terminal sheep are better if you want something delicious for the barbecue but aren’t the low maintenance breed most lifestyle block farmers want to own. What you need is a sheep that’s a mix of the two.

On Ashgrove, they run maternal Coopworth ewes mated to a terminal Suftex sire. The Suftex is a black-faced Suffolk mixed with the Texel breed, which produces shorter, stockier rams with a slightly quieter temperament.

“By crossing a terminal ram over a maternal ewe you get hybrid vigour in your lambs,” says James. The lambs are heavier than their mothers and hardier than their fathers.

Ashgrove Stud sell its Coopworth, Romney, Romworth, and Suftex stock to commercial farmers, with the best ones fetching up to $6000. For large-scale operations, it’s worthwhile paying for superior money-making or money-saving traits such as increased disease resistance or fast lamb growth rates.

For block owners, James says if you have four to five sheep, it’s worth investing $400-$500 in a ram which can ‘work’ for you for 4-5 years. The right ram is the most important factor in any flock as it fathers an entire year’s worth of lambs.

“The ram is the biggest influence and provides 50 percent of the genetics to your future flock.”

HOW TO FIND THE RIGHT RAM

Study the breeder

Breeders should only use their best stock for breeding, and a reputable one will cull any animals that don’t make the grade.

A less diligent one will breed from sheep with faults and offer their progeny for sale.

“Just because a ram has a pedigree with papers doesn’t mean he is going to perform well,” says James. “A ram should come with genetic records, ideally part of Beef and Lamb’s genetic evaluation programme, SIL (Sheep Improvement Limited).

“Eighty percent of rams sold in New Zealand are on SIL, which is world-leading and has fantastic integrity.”

SIL grade and rank the rams. That produces the statistics Hayley puts into their catalogue.

5 questions you need to ask

1. What traits is the breeder recording? These can include:

• fertility;

• ewe feed efficiency;

• lamb survival rate;

• lamb growth;

• disease resistance;

• wool quality;

• meat yield;

• carcass weight.

2. What type of land are they farming, and is it tougher land than yours?

3. Do they have to trim their hooves?

4. Have they fed sheep nuts and grains to make them look good?

5. How often are they drenching? If a breeder is supplementary feeding or drenching every two or three months, you’re probably going to have to continue this to maintain the animal’s weight and condition.

Check the ram

A healthy ram should have a body condition score of around 3 to 4. That’s not skinny but not roly-poly either.

You need to get hands-on to check them, or have someone who can do it for you.

“Examine the ram’s testicles – there should be no lumps or lesions. His teeth should be in good shape, and feet good with no signs of lameness or excessive toe length.”

Check the ram is from a brucellosis accredited flock or has a vet certificate.

Ideally, you also want records showing an animal’s resistance to facial eczema and parasites.

Take biosecurity measures

You don’t want to mate a ram to his daughters or a son with his sisters or mother.

Swapping or borrowing a ram can prevent interbreeding, but be very careful about biosecurity if you do this. Brucellosis is prevalent throughout commercial flocks in NZ, probably more so in smaller flocks, says James.

“If you are bringing an unchecked ram in, I’d suggest keeping him in quarantine until you can get the vet to test him.”

He advocates that all stock coming onto a property should be drenched and kept off pasture for 24 hours to enable the drench to take effect. Internal parasites are developing a resistance to various drench ‘families’, so James recommends using a triple combination drench or one of a new drench family such as Zolvix or Startect.

Romance & the ram

A ram is usually allowed to mate with the ewes (known as tupping) in March or April. James recommends adjusting the timing to suit your climate. Ideally, you want lambing time (152 days after mating) to coincide with the spring grass flush. In Northland, that’s in late September.

“A ewe doesn’t eat excessive feed over winter, but in the two weeks prior to lambing and afterwards when she’s feeding the lamb, she should have all she can eat. She doesn’t want long grass, but ad-lib of 2-3cm-long, good-quality grass.”

James says one ram can service over 50 ewes, but it’s common for farmers to have more than one ram in with a group of ewes, just in case one isn’t performing.

Ewes cycle every 16 days. While most will get pregnant within the first 2-3 weeks, rams should be left in with the ewes for six weeks. The previous year’s ewe lambs can be mated with no adverse effects on health or lifetime performance as long as they are a good size and in good condition.

Most ewes will breed until they’re five or six years of age, although James has a few 10-year-old ewes in his flock.

WHY A RESISTANT RAM MAKES LIFE MUCH EASIER

Resistance to facial eczema and internal parasitic worms are both inheritable genetic traits that a good breeder will test for in their flock.

Facial eczema is caused by a fungal spore that lives low in the grass in the more humid regions of New Zealand. Warming temperatures mean it’s now found in most parts of the North Island and some parts of the South Island.

When eaten, the spores damage the liver, adversely affecting overall health and milk production, reducing fertility, and can cause death, often during lambing. A severely affected animal will show outward (clinical) signs, such as sunburnt-looking skin. However, most animals will show no symptoms and yet still suffer serious liver damage.

Any animal that suffers from facial eczema should be culled, and its progeny not used as breeding stock.

Ashgrove gets all their sires and 10% of each year’s sale rams tested for FE resistance (testing costs $300 per animal). Their Coopworth stud has achieved FE Gold status, which means they show high resistance to FE.

Most terminal rams aren’t tested or selected for FE tolerance, so it’s recommended that they’re dosed with zinc capsules during summer and autumn to prevent FE.

Worm resistance is tested with a faecal egg count (FEC). At Ashgrove, they only breed from stock that show natural resistance. James says that his Coopworth hoggets show significantly lower worm counts than their Suftex.

BRUCELLOSIS

Brucellosis is a venereal disease that can make rams permanently infertile.

It’s passed from ram to ram or ram to ewe to ram through sexual activity. Unlike the rams, ewes are usually only temporarily infectious.

Brucellosis causes an enlargement of the epididymis, or long, coiled tubes that store sperm in the testicles. It can be positively identified (or eliminated) by a blood test for the Brucella ovis bacteria.

There’s no treatment. Infected rams need to be culled. It’s recommended all rams on the same property are also culled, and neighbours advised to test for it.

The disease is not carried season to season in the ewes, so they can be mated to a new ram the following year.

HOW TO BODY CONDITION SCORE EWES AND RAMS

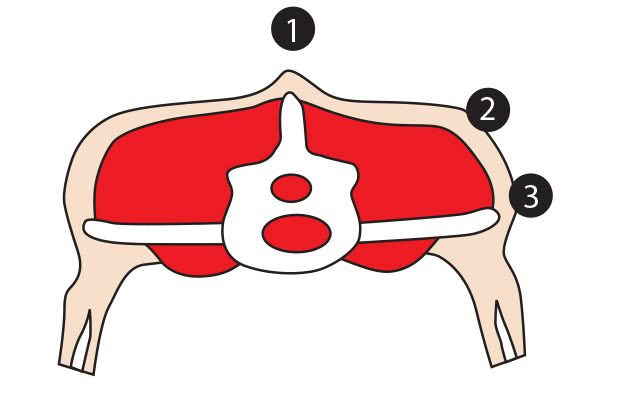

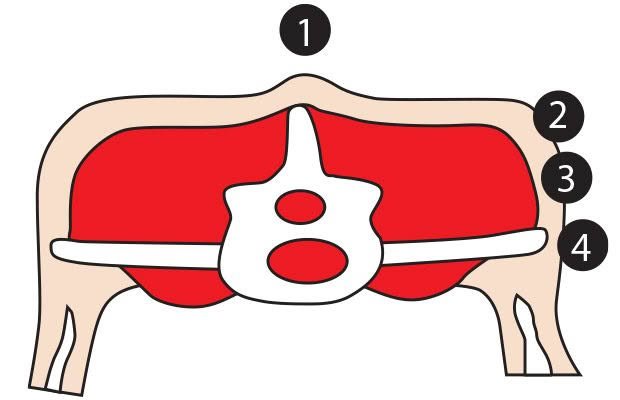

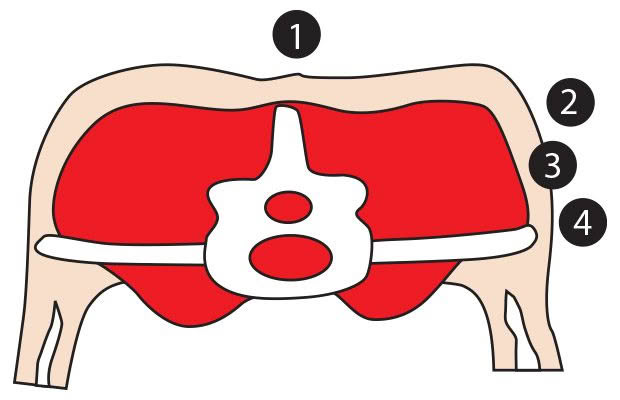

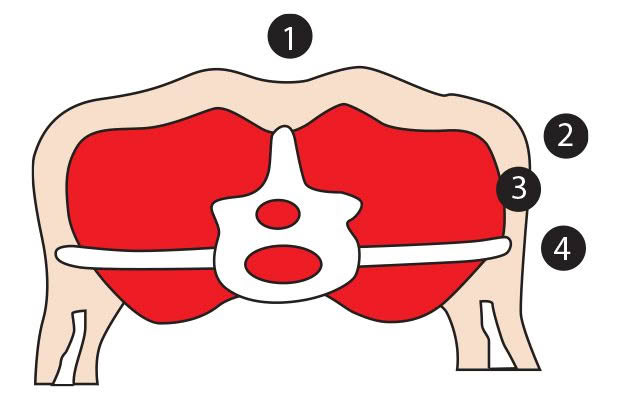

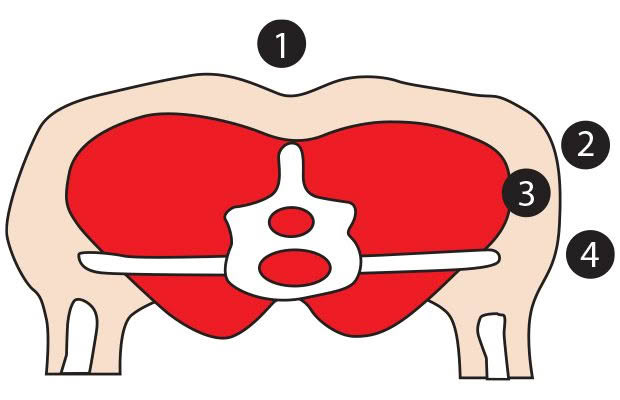

Locate the last rib (13th). Place your thumb on the top of the spine. Place your fingers on the ends of the short ribs, which sit directly behind the last long rib.

Aim for a condition score 3 to 4 for ewes at mating and lambing.

A condition score of 1 is emaciated, and 2 is considered thin. Score 5 is obese, which will reduce ewe fertility and health. The ideal is 3 or 4.

CONDITION SCORE

1.

• Spine prominent and sharp

• No fat cover

• Sharp ends of short ribs, and fingers easily pass under it

2.

• Spine prominent but smooth

• Thin fat cover

• Muscles medium depth

• Short ribs rounded, fingers go under with pressure

3.

• Spine smooth and rounded

• Moderate fat cover

• Muscles medium depth

• Short ribs smooth and rounded, and you need hard pressure to find the ends

4.

• Spine only detected as a line

• Thick fat cover

• Muscles full

• Short ribs can’t be felt

5.

• Spine not detectable, fat dimpled over spine

• Dense fat cover

• Muscles very full

• Short ribs not detectable

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.