Dr Roderick Mulgan: Here we go again

Welcome to the brave new world of perpetual pandemics.

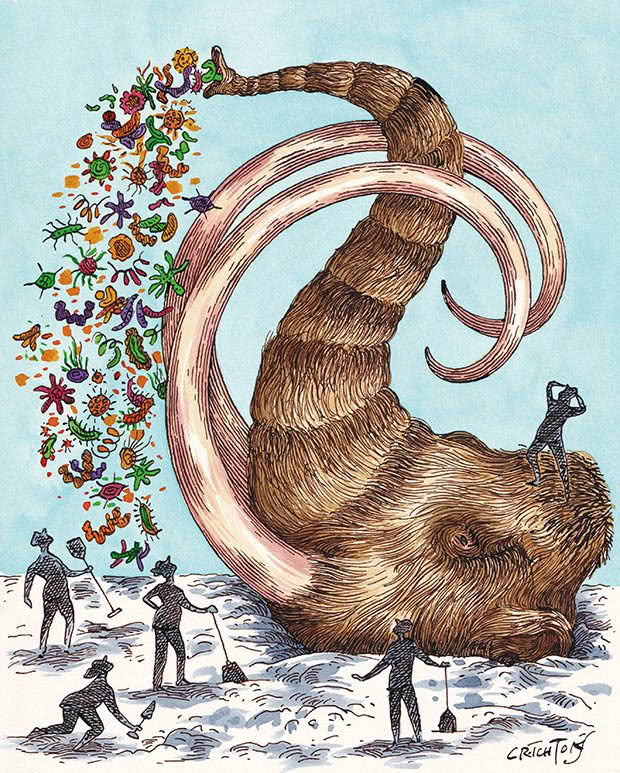

Words: Dr Roderick Mulgan Illustration: Anna Crichton

Scientists in Siberia have a cool new wheeze, digging up mammoth corpses from the permafrost and probing them for novel viruses — the types of viruses that have lain dormant for a million years and never encountered a human. Obviously, nothing can go wrong.

Not to be outdone, scientists in the United States a few years ago found some vials of smallpox at the back of a fridge they had forgotten about1 — the sort of thing you and I do with spare avocados and half-eaten pies. Smallpox is a ghastly, highly infectious viral disease that causes blindness, skin scarring and death. It killed millions before an intense campaign of vaccination eradicated it in the 1970s. It is the only infectious disease humanity has eradicated, but selected centres retain samples for research — if they can remember where they left it.

At the risk of upsetting a few readers, the pandemic we have just come through was mild. Most infected people did not die, and vaccines and drugs proved effective remarkably quickly. No law of nature says it has to be that way. We do not know definitively, and likely never will, whether Covid-19 happened naturally or escaped from a lab, but new risks on both those fronts continue to surround us. If one of those risks crystallises (many would say when), we don’t know how bad the next novel virus will be. Or the one after that.

Nor are novel viruses particularly novel. In the past 20 years alone, there have been several near misses: SARS, then MERS, and a nasty brush with Ebola. We were lucky with these — globally, anyway. They were contained and petered out, but the process that generated them rumbles on. In fact, it is accelerating.

All of these viruses, as well as Covid-19, HIV and influenza, are zoonoses, which means they started in animals and crossed into people. None of them was predicted2, which means we don’t know where the next ones are. This is awkward because the incidence of new zoonoses is increasing.3 More and more are arriving, largely because the circumstances that cause them are. Those circumstances, at core, are the pressures of people pushing into the territory of wildlife, particularly the rich and diverse wildlife of Asia and Africa.4 Roads and plantations lie where trees and wildlife once did. The people concerned are often ones with limited choices and do what they must to survive. Today’s food looms larger than tomorrow’s pandemic.

The risk has a lot to do with bats. Bats, for some reason, harbour a particularly large reservoir of viruses that are capable of crossing into us. They are the only mammals that fly and can easily leave droppings where people and domestic animals will encounter them, particularly as humanity moves closer and closer to their roosting sites or sends bulldozers through them to create palm oil plantations.

Ebola, for instance, seems more likely to break out among humans where the natural forest has been cleared5, and deforestation in Africa is not slowing down.

There is also an elevated risk from mink, which are farmed for fur overseas. The sun has been setting on fur farming for years since welfare issues started to bother consumers, and the current angst about new viruses from mink farms could be the end of them. Which is something.

Then we come to climate, particularly its modern tendency to keep getting warmer. Pathogens in permafrost aren’t just waiting for scientists with shovels. The day approaches when permafrost (ground frozen year-round) will stop being perma and melt into regular earth. The process will release unthinkable amounts of locked-up methane from long-rotten vegetation, which will make warming that much worse, but it will also leave entombed microorganisms free to struggle to the surface on their own.

Likewise, microorganisms already above ground. Warmer and wetter air redraws the territorial boundaries of diseases and the vectors that carry them. Mosquitos carrying the west nile virus are now found in New York, well outside their traditional range. Yellow fever in Brazil and cholera in Bangladesh follow warming events such as El Niño.7 Dozens, if not hundreds, of like diseases are getting a nudge to explore new horizons, where the environment is newly agreeable to them.

Nor are we limited to viruses. Until yesterday, in evolutionary terms, humans regularly exited this planet while young and fit when they met the wrong bacteria. Scratching your arm, getting a chill or delivering a baby were all ways a life-ending infection could make entry, and routinely they did. Average lifetimes were dramatically shorter than now, and infections were a major explanation. That ended in the 1930s when Alexander Fleming had his famous encounter with penicillin mould on a petri dish, and antibiotics became a thing.

Antibiotics are so successful we no longer have bacterial infections on our list of things to worry about, but there is an issue. Drugs such as morphine or blood pressure agents do what they have always done because our metabolisms don’t change, but antibiotics do not act on our metabolisms. They act on independent life forms, infinite numbers of them, which have the numbers and genetic diversity to respond. It is natural selection writ every bit as large as Darwin’s finches.

Bacteria that start out susceptible to antibiotics get meaner and stronger when bombarded by them, and bombarding the natural world with antibiotics is something of a national sport everywhere you look. Doctors freely hand them out for all manner of nuisance symptoms, and many countries allow pharmacies to sell them like wine gums. Major surgery relies on powerful antibiotics; patients undergoing the scalpel are routinely dosed with them for preventative purposes. Farms that pack in pigs and chickens like Lego bricks must steep the feed in antibiotics, the potent broad-spectrum kinds, to stop disease from breaking out. It is happening all over the planet. Bacteria that seek to beat our weapons are getting every encouragement.

Some of the most successful in the drug-resistance game are long-forgotten enemies such as tuberculosis. Drug companies are not responding. Contrary to expectations, the problem does not mean an investment opportunity. Not only are there technical barriers to finding a breakthrough new drug, but any genuinely innovative antibiotic would also be reserved by law for the few very sick people who really need it, which is good stewardship, but a poor return on shareholder funds.

The World Health Organisation reviewed the situation in 2020 and reported that 43 antibiotics were in development worldwide. Only a handful of them used novel mechanisms (as opposed to being derivatives of existing agents), and none was intended for multi-drug resistant bacteria.8 By contrast, about 4000 new drugs were being developed for cancer.

Which means we need to be careful with the antibiotics we have. Don’t take them for colds and flu, which are self-limiting without treatment, and don’t buy meat and eggs from factories. Plenty of farmers combat disease by keeping their stock in sunlight and open air; look at their websites and seek out their brands.

Historians may one day write that Covid-19 ended a short golden era when humanity temporarily overcame its microbiological nemesis. If penicillin marks the start of that era, we have enjoyed 80 years of it. How many more we are destined to enjoy remains to be seen.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.