Meet the block owners with 14 hectares dedicated to regeneration

This Bay of Plenty block is designed around improving the health of the planet.

Words and photos: Sheryn Dean

Who: Lisa Eve, Marcus Baker, Maddie and Leo

What: 9ha, plus 14ha regenerating, covenanted land

Where: Awakeri, 1 hour east of Rotorua

Web: ecohotwater.co.nz

When Lisa Eve and Marcus Baker decided to settle down and raise their family, they didn’t just want to put down roots. They wanted to make the world a better place.

They’ve trained for it too. Lisa did her thesis on Bird Life in Urban Forest Fragments and Marcus works in the alternative energy industry. Minimising their environmental footprint and enhancing natural ecosystems are fundamental to their way of life.

But first, they had to find a little part of the world to call home.

Lisa is originally from Northland and met Marcus while working in England. They returned to NZ and started searching for somewhere to live. Northland was too humid, Tauranga too crowded. The Coromandel got close but wasn’t quite right.

The winning spot was in the hills of Awakeri, a 20-minute drive south of Whakatāne. It ticked all their dream block boxes:

• close enough that they could (at a stretch) cycle to town and the sea;

• bushland;

• a water catchment;

• free-draining soil.

The problem? The 44ha farm was beyond their budget.

The ash-loam soil was nutrient-deficient, but warms up quickly in spring. Lisa and Marcus have oversown a range of diverse species of herbs and grasses to provide grazing for their cattle.

When you talk to Marcus, it doesn’t take long to realise he believes almost anything is possible. At work one day, he heard about a couple who wanted to buy the same piece of land, but also felt it was too much for them. Would they consider sharing it?

They would, and they did. The two couples pooled their resources, bought the land together, then subdivided it. Within nine months, they each had title to their own piece of paradise, splitting the grazing land two-thirds to the other couple, one-third to Lisa and Marcus.

Marcus makes light of the subdivision process, saying the few bumps they encountered were sorted reasonably easily. Their original purchase was made jointly. They then created a legal document that set out their objectives, and there was an escape clause to buy each other out if things went wrong.

Marcus says he used the same approach to the subdivision process as he does in his business.

“You go to people and say, ‘this is what I want to achieve, how can we make this as easy as possible for you?’”

The local council wanted the entrance to be made safer for traffic turning into the driveway, so they moved a power pole, and constructed a pull-in bay on the side of the road.

Lisa and Marcus’ share of the property consisted of a couple of boggy flat paddocks and a small valley leading up into a patch of native bush. Fourteen hectares of the bush-clad headwaters is now covenanted with the Bay of Plenty Regional Council. Stock are fenced out, willows poisoned, blackberry sprayed, pests controlled, and native plants added.

Their indigenous wonderland also protects several ephemeral springs. The couple siphons water to supplement their roof supply for the house, garden, and stock, and the excess flows down the valley.

THE PLANTING PROJECT

The first pond captures and slows the water coming from the springs further up the valley. It also provides a playground for Leo who pole paddles through the shallow water.

One of their best investments was hiring a contractor who turned out to be an artisan. He dug out a driveway, building platform, a series of three ponds, and drains that take water down the valley. To create what is now an abundant food garden, topsoil removed to form the driveway was layered over the ground, then planted in mostly heritage or hardy home orchard varieties.

The design slows water moving through the environment, giving it time to seep into the soil. It also drained stagnant land, creating wetlands that now sustain native ecosystems.

Next, there was a lot of planting. Lisa says in hindsight she’d have used the digger to scrape away the grass as preventing it from smothering hundreds of native plants has been the hardest job so far.

It took trial and error to determine which plants grew well in their quick-draining ash loam in an area that can get hit by frosts down to -6°C in winter. Now they know to plant the hardy establishment trees, including:

• Pittosporum varieties such as tarata (Pittosporum eugenioides);

• flax (harakeke, Phormium tenax);

• cabbage trees (tī kōuka, Cordyline australis);

•māpou (Myrsine australis);

•Griselinia;

•tanekaha (celery pine, Phyllocladus trichomanoides).

Mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium) were used in the wetter areas, kānuka (Kunzea ericoides) and tōtara (Podocarpus totara) on the drier slopes.

“Another one that does surprisingly well is hohere (lacebark, Hoheria sextylosa) – the birds love it as a perching and nesting tree.”

Lisa has found she gets a better survival rate if she plants these species 600mm apart. Three to four years later, once they’re established, she interplants with more diverse species.

“They’re the more interesting plants,” says Lisa. “Kōwhai, rewarewa, Pseudopanax, rimu, lancewood, kahikatea.”

That planting strategy is the result of hard-won experience.

The understorey is flourishing amongst the established bush now stock don’t have access. The area is also protected forever by a covenant.

“Firstly, we planted a bunch of species that we then discovered just didn’t like it here, generally due to frost sensitivity, as we get much colder winters than people expect for the area.

“The second issue was that when planting at the recommended distance (the regional council suggests 1m or even more) they didn’t thrive, often due to grass and weed competition. We did so much planting, we just didn’t have the time to release them (from under grass and weeds) as often as they really needed.”

Lisa’s theory is planting trees closer together mimics natural forest habitat. Whatever the reason, using 600mm spacings has transformed their block and greatly reduced the follow-up work.

“You can barely tell the difference between one area planted six years ago (using the original 1m spacing) and one planted just three years ago with 600m spacing. By planting more closely, we lost far fewer plants and had to do way less releasing and weed control, and they just seemed to come away much more quickly. More money spent on plants, but less money lost because the plants did better.”

Changing plant suppliers also made a difference.

“Our local nursery is coastal, no frosts. We found the plants would get in the ground and sulk. Now we get them from a nursery near Rotorua, which is colder than us, and so they come over to our place and revel in the relative warmth.”

She’s also created an homage to one of her childhood joys, watching tūī. A flax hedge sits on the slope just below their home’s living area. It puts the flowers at eye level so the family can delight in watching 20-30 tūī at a time, fighting, feeding, right in front of them.

The massive increase in birdlife is one of the biggest changes they’ve seen in the last 10 years. They now share the valley with itinerant tūī, kāka, riroriro (grey warbler), and korimako (bellbird). Two weka pairs stalk across the lawn, pūkeko chatter in the bottom pond, and spring is heralded by the whistle of the pīpīwharauroa (shining cuckoo).

THE HOUSE OF GOOD ENERGY

Rescue dog Tessa now leads the good life: her parents work from home, she has kids to play with, a block to romp around, and a cosy house.

At the same time, Marcus focused on building their 150m² off-grid house.

“I decided to project manage it myself, which was rather ambitious.”

The modern, comfortable house nestles behind a spur halfway up the valley. It’s carefully positioned to take advantage of the sun, sheltered from the wind and the outside world by the surrounding hills.

“I would never build on top of a hill,” says Marcus. “I like being tucked away.”

Huge, double-glazed glass doors open the living areas to the outdoors in summer. In winter, the sun warms the concrete floor, acting as a heat sink. It’s insulated with 200mm of local pumice instead of polystyrene, one of Marcus’ innovations to reduce the home’s environmental footprint.

Even in mid-winter, when frosts coat the valley in white crystals, his expertise in natural heating and cooling systems is apparent in the comfortable ambient temperature of the house. At its heart is a wood-fired range cooker, their main cooking source in winter, linked to a wetback to heat water.

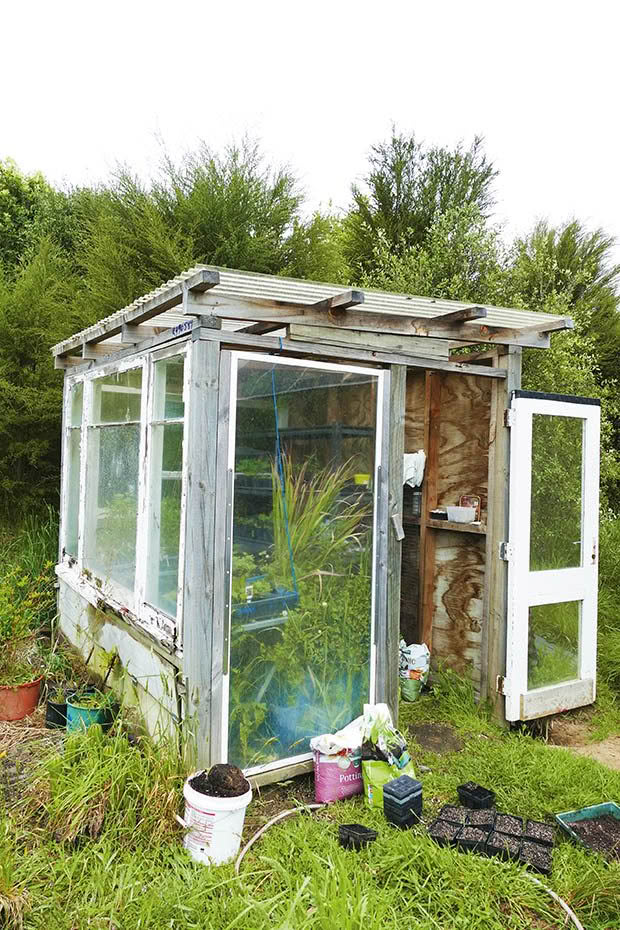

The glasshouse constructed from recycled materials is very effective and cost nothing but time. The couple mainly uses it to propagate native seedlings.

But Lisa’s highest praise is for the underfloor heating and hot water system, designed by Marcus. He considers pellet burners to be the most efficient, economical, and easiest way to heat water, and their home uses an Easypell pellet burner which sits in a shed near the house. The gentle radiant heat it emits is the ultimate luxury, says Lisa, maintaining the home’s natural humidity. The boiler also serves radiators in a cabin that Lisa and Marcus use as an office and visitor accommodation.

Other innovative features include solar panels for power, polyester insulation, and locally sourced, untreated Lawsoniana cladding.

The wooden joinery is totara. It was a nightmare to find enough good quality wood, says Marcus, but worth it for what it adds to the atmosphere of the house.

THE RESULT

Lisa’s fence of flax feeds 20 to 30 tūī at flowering time.

Their block is now at the point where it ticks over by itself. They have six cattle on the 4ha of grazing land, the fruit trees and vegetable garden are producing, and their flock of chickens provide eggs. They could be self-sufficient if they needed to be, says Lisa, but they prefer to trade with a network of friends.

They’re now more focused on their careers. Lisa works in the waste reduction field, and the couple were the founders of Community Resources Whakatane. It’s an initiative committed to eliminating waste, and it’s now a self-funding, self-supporting enterprise.

Today, she works as a senior consultant developing strategies and providing advice on waste policies at a government and corporate level.

Marcus runs Apricus Eco Hot Water & Heating, designing and installing sustainable and environmentally friendly central heating and hot water systems. These include solar power, pellet boilers, and CO2 heat pumps (CO2 is considerably more benign for the environment than traditional refrigerants) for homes and commercial buildings. His knowledge of the ongoing consumption, long-term impact, resources required, waste generated, and environmental effects of each option is extensive.

The boggy land between the middle and bottom pond was raised with topsoil from the building site and now provides a moist but free-draining site for the orchard of heritage fruit trees.

The couple says they wouldn’t be at this point in their lives without the enormous contribution of friends, woofers, and family who helped them with all the work setting up their block and home. Among them are two standouts.

“My mum and dad have done so much here, it’s hard to know where to start,” says Lisa. “This place would be years behind where we are without their contribution.

“My dad built our beautiful bespoke kitchen cabinets. They’re retired schoolteachers, but here they’ve been electricians, builders, preservers, gardeners, plumbers, fencers, master Lego-builders. There would be many more loose wires hanging from the ceiling, that’s for sure.

“Almost anywhere we go on this place, we can see something that they’ve helped with. They timed their retirement well!”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.