A home drenched in colour is perfectly suited to this inspiring librarian

A plant wall in Kim Tairi’s Auckland apartment creates a cosy nook that is a little bit disco. Kim wanted the kitchen to appear separate to the open-plan living area and used pot plants to create a living wall. Her quest to indigenise includes supporting local Pasifika and Māori artists. A beautiful hot-pink floral Sione Monū banana is incorporated into the plant wall.

The well-curated life and meticulously ordered home of a university librarian belies the chaos of her insatiable curiosity and the challenge of discovering her tikanga.

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Jane Ussher

Kim Tairi is ready to chat, with an iPad to hand with notes prepared for her interview. Few people are that organised. Most wing it.

“I’m a librarian, so I am a planner,” she says. Life for the Auckland University of Technology librarian (kaitoha puka) hasn’t always been so ordered. Her early years in Ōtepoti/Dunedin in the 1980s were anything but; the eldest of four, in a state house in the suburb of Corstorphine, raised by a solo parent working all hours to keep a roof over the heads of her young children.

“My parents met at a dance in Invercargill; Dad was working in the freezing works and then on fishing boats, and Mum’s family were Invercargill locals. Today they probably wouldn’t get married, but Mum got pregnant at 17, and that was that. She was the first Pākehā to marry into Dad’s family. He is Waikato and one of 14 from Maungatautari Marae near Cambridge. Mum was overwhelmed and didn’t encourage us to explore our Māori cultural side. Dad’s generation was punished for speaking te reo Māori.”

A love of pottery and ikebana led to experiments with making small hand-built pots. The vase is by wāhine Māori ceramist Esther MacDonald of Thea Ceramics.

Her parents’ marriage broke down. Her father left Dunedin for work in Australia, and her mother took on multiple jobs, including taxi driving, joined the Values Party and started working for a women’s refuge, herself a victim of family violence. Kim took responsibility for the family’s laundry, babysitting and cooking and concluded that she wasn’t getting much from school. Even so, she considers her Queen’s High School headmistress, Patricia Harrison, a stroke of good fortune. Patricia gave Kim the idea that girls could do anything and allowed the (very few) Māori pupils at Queen’s to connect with their culture. Not that Kim did much of that at the time.

At 14, she was already rebelling, pulling away from her family and gravitating towards the local arts and music scene. With hindsight, she recognises education as giving her and her family a leg up from poverty.

“Poverty was the reality for most of our early life. The only way I’ve gotten what I want is by having the right qualifications to get better jobs. Once I’d got a better job, I’d think, ‘I am not quite there yet, and I have to keep going.’ I’d study more.”

Her early forays into study gave no indication of the academic success she would later achieve; one semester studying arts at the University of Otago before dropping out and one year studying nursing before pulling out. Then she fell in love with a musician — a guitarist — and got pregnant, married and moved to Australia, part of the Kiwi diaspora (including her mother, her two brothers and her sister) looking for a better life. She loved her husband, the father of her two daughters, but she didn’t love the addictive personality that led him to heavy drugs.

“It is the chicken-and-egg thing. I don’t know if it was depression that came first or the experimenting many of us do in our youth, but he loved drugs. I didn’t have the temperament and stopped when I got pregnant. But he couldn’t. A lot of people didn’t know about his addiction. My close family did as they had to help me many times.”

Mostly that help came in the form of money to retrieve household items her husband had pawned to pay for drugs. “It was a loving but tumultuous relationship. Sometimes I’d use my entire pay cheque at Cash Converters to buy back the items he’d stolen from friends and family.”

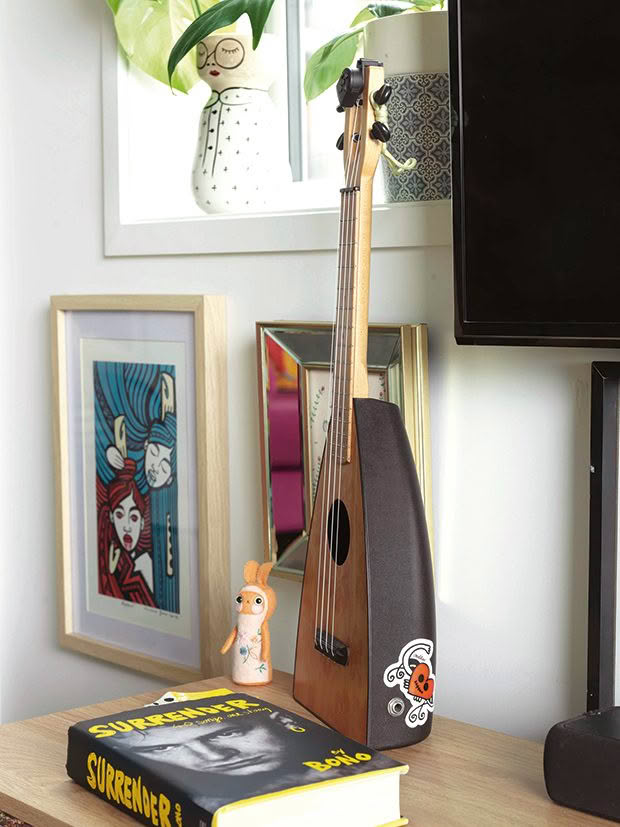

Kim’s ukelele playing was inspired by meeting a bunch of ex-Wellington Ukelele Orchestra folk at a party in Pōneke with her good friend Joyce Seitzinger in 2012. She has four ukuleles at home and one in her office. Still a learner, she is keen to get back to lessons.

Kim realised she would need to be the breadwinner. “I had done some library work and childcare, but I knew that wouldn’t sustain us. I needed to go to uni and get qualified. I started as a library technician, a para-professional job, at a TAFE in Melbourne (like a polytechnic), and I kept going. I was 16 years in the same job, becoming a qualified librarian first, then doing my master’s in tertiary education. I got the bug, and it felt like I was at school for a very long time.”

During the early years of Kim’s nearly three decades in Naarm (the traditional Aboriginal name of Melbourne and home of the Kulin Nation people and how she refers to Melbourne), her husband looked after their children.

“He was the primary caregiver while I returned to uni; he was terrific in allowing me to study and work. I progressed quickly into management and leadership roles, and he was in and out of work. Outside of the family, no one knew about the drug addiction. Our daughters didn’t know there were drugs involved until their late teens.

A maximalist and a collector, Kim has filled her home with bright, bold art. Nearly every wall is covered. The gallery wall above her sofa features art made by friends, whānau and her own embroidery.

“Mum was great; she had a good relationship with the girls, babysitting and taking me shopping because I had no car. We joined a housing co-op to keep a roof over our heads and learned a lot from it. I did book-keeping, learned about leadership and running a committee, doing the minutes, and it all complemented my studies.”

Kim says she survived those difficult years, and her daughters thrived thanks to whānau support, especially from her sister and brother-in-law. She and her sister are very close.

“They had to deal with the fallout when things weren’t going well and were really supportive; if I were short of money, they’d lend it to me. My husband’s parents were amazing too.”

Her marriage eventually ended — something for which she accepts considerable responsibility. Her husband had begun using P, and his personality had changed. She sought solace elsewhere. The couple separated, and a few years later, he died at 46.

“A heart attack, damage from all those years of drug abuse. With the ‘ice’ [as P is known in Australia], we’d lost the gorgeous man that he was, that great father to our two amazing girls. He’d done the lion’s share of the parenting, and being a great dad was the most important thing to him — when drugs weren’t involved. But that’s addiction.”

Fortunately, Kim was on her way to academic success and in a good job. She loved the intellectual environment of a university library. “I wanted to work where a person like me could thrive; an indigenous, first-in-family person from a small town with a story similar to mine could grow and learn.”

Her life in Naarm was settled and secure; her two grown-up daughters had their own lives. In 2016, an approach from a recruiter for the Auckland University of Technology for a role as university librarian was unexpected yet not entirely unwelcome. Perhaps a return to Aotearoa could allow her to reconnect with her Māori culture, she thought.

“My re-Maorification journey… as Dr Moana Jackson calls it. I was at the stage where my children had left home, and I wanted a challenge. And even if I had imagined my next move might be to Europe or the United States, I knew that from Aotearoa, I could hop on a plane and be home to my girls very quickly.”

That didn’t quite work out, thanks to a certain pandemic, and Kim first met her first grandchild when he was nearly a year old.

“But coming back to Aotearoa has given me an awesome job, a new life, a new relationship and a chance to start being an adult finally — properly. I feel like I am living my own life rather than trying to run away from something I didn’t know how to deal with. And being a kuia and embracing ageing and the gift of my mokopuna.”

What is still very much a work in progress is the journey back to the marae near Cambridge from where her father left as a young man in search of work in the early 1980s.

“I’ve always identified as Māori, but I didn’t understand that childhood label of being ‘half-caste’. What did it mean? That a portion of my blood defines who I am? I never knew where to go with that, but now, as one of very few Māori women in university leadership, it is important to be confident in where I stand.

“Learning te reo Māori means learning tikanga. It means putting myself in situations where I am uncomfortable because it is embarrassing to be Māori and not to be able to speak Māori fluently or have strong cultural connections.

Kim chose her 64-square-metre apartment in the Mt Albert Tuatahi Ockham complex because it was a small blank canvas with a shared community library and events space, designed in partnership with one of the local iwi. Having lived in a housing cooperative in Australia, she wanted to be part of a community.

“I am very much the teina, the younger sibling, learning from incredible people. For example, I work with amazing rangatira, such as Professor Ella Henry, our dean of law, Dr Khylee Quince, Dr Robb Hogg and Dr Valance Smith. I am treated like a peer. These are people with an incredible wealth of knowledge in things Māori, and I get to learn from them.

“I am in awe of the people I have met and worked with since I came back to Aotearoa. Their goal is to enhance the mana of students and colleagues and uplift everybody through understanding what it means to live in Aotearoa with Te Titiri as the founding document of nationhood.”

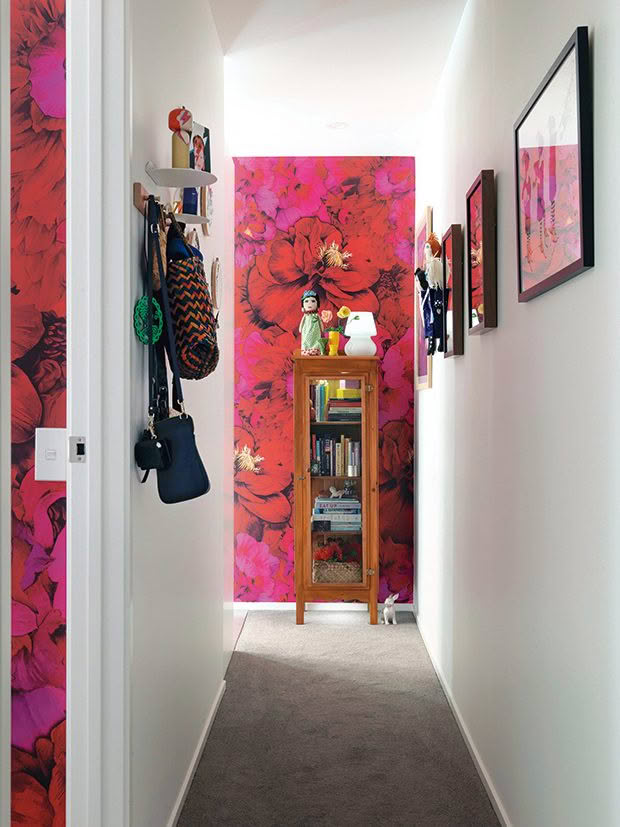

The hallway and bedroom, although small, use colour and art for maximum impact. Her mother-in-law, Annie Baird’s paintings, including portraits of Kim’s tamariki, who are now grown up and living in Australia, are some of her most prized possessions. Kim misses them and her mokopuna immensely.

Her return to the family marae is not as regular as she’d like. Her electric bike is excellent for inner-city life, with a 20-minute daily commute to work along the city cycleway, but not so great for nipping off down the Waikato Expressway to participate in hapū activities.

She’s working on it. In early 2020, her father’s siblings reunited and spent a week on the marae. “Our challenge is how we bring people home, connect them to those who have stayed, and for those of us returning, learn how to contribute in a meaningful way. It is a lot of work for the ones running the marae, at every tangi and every event. And there are a lot of us who want to return and to be more active

and contribute.”

So that girl from Corstorphine, who resented being called a half-caste, now wants not only to embrace her Māori heritage but also share it with a wider community, for she believes it uplifts everyone.

SHHHH…

“Libraries are not always the quietest places these days,” says Kim. There are 325 public libraries in Aotearoa, all providing free internet. Some 30 per cent of New Zealanders are active public library users. But are libraries still relevant today in the age of digital search?

“Yes,” says Kim, “perhaps more so than ever.

“The pandemic has shown us how important it is to find trusted, accurate information when making decisions about virtually everything in our lives. Have you tried ringing a utility company or any government department lately? The first information you will get, probably from a recorded message, is that the website has the information you need or a form to download. How to do that if you are not digitally skilled?

“Libraries are staffed with skilled, friendly people who can help community members develop the digital and information literacy skills needed to survive. In today’s world, disinformation and fake news are rife and assisting people to find accurate and trustworthy information is a big part of what librarians do.

“We take seriously our role in providing equitable digital opportunities or digital equity. And, of course, libraries are the place to fill the kete (bag) with knowledge.

“Te manu kai miro nōna te ngahere; te manu kai mātauranga nōna te ao,” says the whakataukī.

“The bird that eats the miro berries, theirs is the forest; the bird that consumes knowledge, the world is theirs.” — Elder, H, 2022.

“Libraries are often referred to as a third place — open to everyone. A place to study, research, rest, play games, seek respite and connect.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.