‘Never a dull moment’: This Waipu couple revels in raising goats and making cheese

Seven years ago, David and Jennifer Rodrigue were townies, dreaming of the country. Today, they produce award-winning boutique cheeses and share their lives with a herd of happy princesses.

Words: Sheryn Dean

Who: David and Jennifer Rodrigue

What: Belle Chèvre Creamery (pronounced ‘shev’), 18 Anglo-Nubian milking does

Where: Waipu, 30 minutes south of Whangārei, Northland

Land: 16.6ha (41 acres)

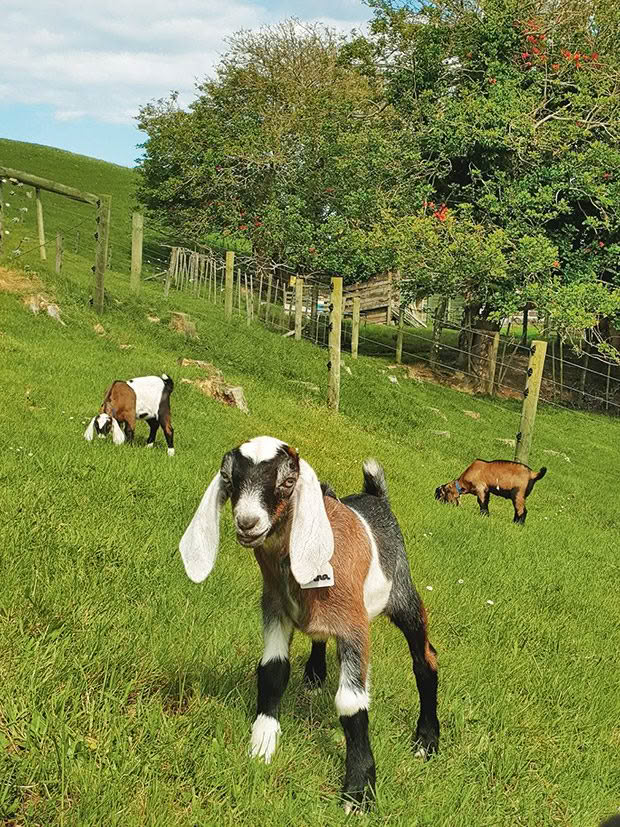

On emerald-green rolling hills, a troupe of Anglo-Nubian princesses rule a tropical kingdom on the outskirts of Waipu. Tinkling with jewellery (Swiss goat bells), they’re treated to pedicures, head massages, hairstyling, and offerings of banana peels and olive branches.

Vixen, Venus, Zephira, Zena, Zephyr, Annabel, Argo, and their friends are the backbone of David and Jennifer Rodrigue’s boutique cheesemaking business. Belle Chèvre Creamery is a passion, a lifestyle, and a commitment that Jennifer revels in. She says it gives them the best of everything: intellectual stimulation from the science of cheesemaking, creativity, routine, variety, and exercise.

“I like the routine and the different seasonal fluxes waxing and waning, there’s never a dull moment,” she says. “Off-season projects get added to the list, done, and then we’re back into milking. (Farming) keeps you both physically and mentally active.”

THE CHEESE NEW YEAR

Mating is in March. Kidding begins in late July. It’s carefully timed to start eight weeks before the flush of spring grass, so peak milk production coincides with the best nutrition. Kidding is spread over two months, so there’s always enough milk to meet the demand for their cheeses over the tourist season.

The kids are hand-reared for 4-5 months. Giving the kids their breakfast is Jennifer’s favourite job. By lunchtime, she’s tucked away in the hygienic cheese room, busy turning their mothers’ rich milk into artisan goodies.

Every day from kidding until the does are dried off in April, Jennifer crafts 30 litres of fresh milk into cheeses using culture and rennet. Her recipes are from around the world, but she gives them her own twist to create unique culinary delights. There is the Greek Betta than Feta (and it is); her signature French soft goat cheese, chèvre; Zalloumi, based on traditional halloumi; Manaia Ma, a pyramid covered with black ash and white mould named after their local mountain; a hard cheese called Pepper Jacks from an American recipe, and chilli-infused queso fresco which originates in Mexico.

Her market stall exclusive is bonbons, chèvre cheese coated in freeze-dried raspberry powder and dipped in Whittaker’s dark chocolate – three superfoods combined into what Jennifer describes as a healthy indulgence.

It all started in a tent at the Whangārei A&P show when cheesemaking teacher and NZ Cheese Awards judge Jean Mansfield gave a feta-making demonstration. Jennifer left with a culture kit, a recipe book, and a ton of inspiration.

It took a few years, but when they saw a secluded 16ha block just five minutes from Waipu, they made the leap from urban business professionals to lifestylers. They chose goats for their manageable size and they’ve found them easy to work with. David says he never needs to manhandle them; he just entices them, training them to a routine which they’re happy to follow.

The breed they farm, Anglo-Nubians, are considered the Jersey cows of goats. They’ve been selectively bred to produce a higher fat milk than other goat breeds, a trait that results in a higher cheese yield per litre of milk.

Their first goats, Snow and River, were Jennifer’s 2015 Christmas present. She would save their milk for several days until she had enough to make a batch of cheese. The herd quickly multiplied, and Jennifer made cheese for friends and family.

ON GOAT BREEDS

The predominant dairy breed in New Zealand is the white Saanen goat, known for its high-volume but lower fat milk production.

Saanen: 3-5 litres of milk per day, average 3.8% fat. Most of their milk is processed into infant milk powder for export.

Anglo-Nubian: average 2 litres of milk per day, 5.5% fat content in spring.

FROM BEGINNER…

They were having so much fun, they decided to look into the Ministry for Primary Industries requirements for commercial production. Jennifer says it’s an involved and daunting process. A webinar from the NZ Cheesemaking Association helped them compile two Risk Management Plans, one for the farm dairy and another for the cheese processing. “It took us over a year to get our head around it and get the shed ready.”

Jennifer admits her least favourite task is bookkeeping. That’s unfortunate as MPI requires intense record keeping with an annual audit, and regular testing and reporting requirements. One of the main requirements is to have clean water. The couple catch rainwater, so they have bug guards and bird deflectors on the guttering and installed a UV treatment system. They change the bulb and filters annually and submit test results to prove there’s no E. coli in it. Jennifer can use the water for cheesemaking without having to boil it, safe in the knowledge it contains no bacteria or chlorine that affect the cheese cultures or people’s health.

In 2020, the herd grew to over 50 and they took the opportunity to send some of the older does to a bush block for retirement. The couple are registered breeders, preferring their own hand-raised goats as they’re easy to train, versus buying in stock. Excess kids are sold to good homes.

There are 18 does in the milking herd and two bucks. Jennifer says that’s the right size for each princess to get personalised attention and she has no desire to become a large commercial operation.

… TO AWARD WINNER

In 2019, Jennifer entered the Paparoa Ag Show cheese awards, where Jean Mansfield was judging. Jean, a senior judge for the NZ Cheese Awards urged her to enter what she describes as her outstanding cheeses. Jennifer won the New Zealand Specialists Cheesemakers Association Home Crafted Cheesemaker of Year Trophy in 2019.

She was so inspired, she entered again in 2020 and won three gold and three silver medals. In 2021 – the awards she rates as most special – she got to celebrate another gold medal haul, this time in person with her fellow cheesemakers. She was also first runner-up for the Champion Goat Cheese trophy.

“Her subtle mingling of flavours without overpowering the underlying freshness of goat milk is difficult to achieve,” says Jean. “Soft cheeses require a delicacy of touch and her results are a triumph.

“It’s wonderful when home cheesemakers can make the transition to producing commercially. Jennifer is an inspiration for other upcoming cheesemakers to enter the specialist cheesemaker homecraft category and make their skills known.”

Jennifer only started making artisan cheeses six years ago, but quickly developed award-winning recipes.

If you want to try some of Jennifer and David’s award-winning cheeses, they sell them at the monthly Waipu market, a couple of outlets in Whangārei, and to a restaurant in Russell. However, the one they love best is the Roving Rural Market where suppliers take turns hosting the market on their property. Jennifer says it’s great fun trading with the other vendors, including a Polish breadmaker, a Russian chocolate-maker, and the local berry grower.

Ask her what advice she’d give anyone wanting to raise goats or make cheese, and she’s quick to reply. “Do it. Do it sooner rather than later. It’s a great life.”

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF AN ARTISAN CHEESEMAKER

6am: First thing is to feed the kids. It’s the best part of the day. At the moment, we have 10 babies which get a combination of colostrum milk and baby powder.

6:30am: David and I bring the does in for milking and feeding, then clean up the shed.

8am: I filter the milk and pasteurise it by bringing it up to 63°C for 30 minutes. During that time, I clean the milk buckets and filters etc. Then I stand it in sinks of cold water to chill down to 30°C.

9am: I have breakfast, check emails and decide what cheese I’m going to make for the day. If a market is coming up, I’ll make a fresh cheese; if not, I’ll make a hard cheese that needs to age for longer. I don’t make blue cheese at all as the culture so easily contaminates everything.

11am: I culture the milk and let it incubate for an hour. There’s always something to do in this time – moving cheeses in brine, packaging etc. If David is out making deliveries, I’ll go and give the babies their lunch.

1pm: This is when I finish the cheesemaking – cutting the curds, salting, straining, shaping, pressing to the recipe. Meanwhile, David is out attending to jobs on the farm, occasionally coming to the door to discuss something, and generally being a goat slave.

5pm: As with any farm, there’s the afternoon feed, moving them from paddock to housing, and then a baby feed again at dusk.

7pm: The day’s work is done and I think about dinner – there’s always cheese! If my son is here, he’ll cook something, and sometimes friends come by with food, but there isn’t a lot of time for socialising while we’re milking. It’s a pretty rigorous season, seven days a week for – last year – 221 days.

We’re trying to get it to 240 days if we can get more drought-resistant grasses to provide adequate feed. From Labour Weekend until February, we spend more time going to markets. After milking finishes in April, we have a month or two to catch up on the odd jobs and take a holiday.

JENNIFER’S CHÈVRE PARCELS

Chèvre goes well with sweet and savoury flavours. Jennifer often takes it to market rolled in toasted walnuts and drizzled with honey. However, her favourite take-a-plate is a simple dish of grilled eggplant with chèvre, smeared with homemade basil pesto. It’s a good side dish or substantial enough for a vegetarian dinner. Chèvre keeps well, so it can be served at room temperature with a salad for lunch the following day.

DEALING WITH PARASITES

Goats are very susceptible to intestinal parasite infections (worms) as they don’t build immunity to them like sheep and cows do. Most drench products are designated ‘off label’ for goats, as they’re designed for use in sheep. This means they aren’t officially certified for use in goats in NZ (due to the high cost) but are known to be effective.

However, you can’t use the milk for the 35-day withholding period after drenching. Regular use of worming treatments also contributes to the build-up of drench-resistant parasites. Jennifer and David test their goats’ manure regularly to identify and monitor parasite levels. They use a wormwood supplement and Bioworma, a natural fungus that kills the worm larvae in the paddock, neither of which has a withholding period. They only drench when necessary but are still seeing some resistant worms.

They grow a lot of trees for fodder, so the goats aren’t always eating near ground level (where worm larvae live). They also cut and carry branches of willow, olives and friend’s prunings to the herd. Once the goats finish grazing a paddock, the couple sends in their small herd of cattle. Cattle don’t host the same parasites as sheep and goats, so they help to reduce larvae numbers in the pasture.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.