Is plasma the new gold standard for baby livestock?

Young livestock need antibodies for good immunity, but some miss out. Dr Sarah Clews outlines why they’re important, and a new option she offers.

Words: Dr Sarah Clews, BVSc

If you’re new to farming, welcome to the world where everyone is obsessed with colostrum. It’s the first milk a mother produces after birth, a thick, golden colour, rich in protein and fat. It’s also full of antibodies that kickstart a baby’s immune system.

WHY COLOSTRUM IS CRUCIAL

Ruminants have a very different reproductive system to humans, and no antibodies are transferred in utero. Instead, lambs, calves, kids, and cria need good quality colostrum from their mother in the first few hours of life to receive the basics of an immune system. They’re born with loose gaps between the cells lining the gut, allowing them to absorb the large antibodies in colostrum. However, these cells start forming an ever-tightening bond very quickly, so there’s only a limited window where antibodies can cross into the bloodstream.

A healthy baby ruminant will stand and drink from its mother in its first two hours of life, taking in the maximum possible number of antibodies. A drink in the first four hours will still yield enough antibodies for good protection. But by 12 hours, only 10% of the antibodies are absorbed; after 24 hours, none will be absorbed.

Colostrum powder products may help if you find a baby before the 24-hour mark, but often by the time you realise there’s an issue, it’s too late. A lamb, kid, calf or cria that doesn’t receive any or enough colostrum is usually immunocompromised and will have health and growth issues. Those most at risk are animals that:

• don’t stand to drink quickly enough;

• are weak after a difficult labour;

• are mis-mothered or rejected by their mother;

• have a mother who isn’t in good health.

They’re at high risk of picking up deadly infections from common, usually harmless bacteria in the environment.

THE SOLUTION

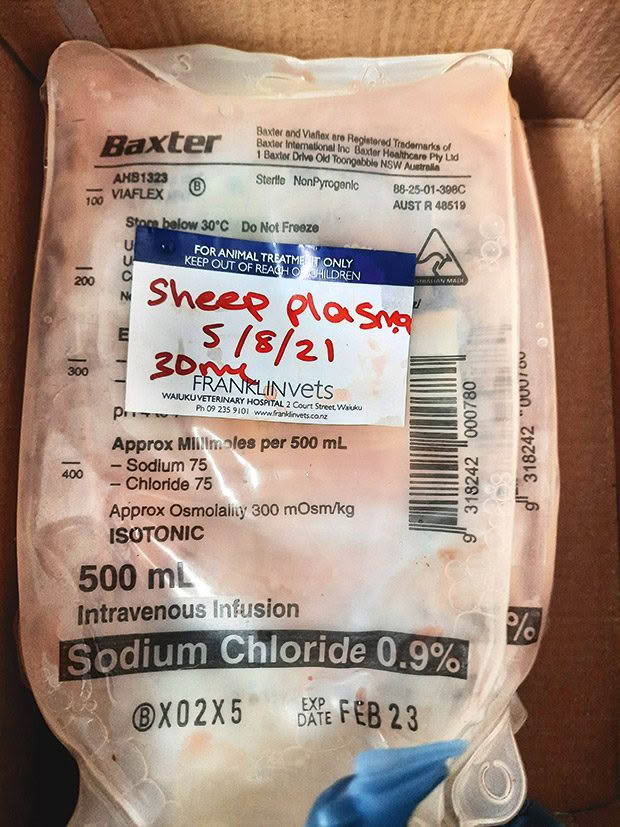

Over the last two years, I’ve worked on an initiative that transfers antibodies into the bloodstream of lambs using plasma transfusions. It takes special machinery and skill to separate plasma – the component in blood that carries the immune cells – from blood, and it’s tricky to inject plasma into the bloodstream safely.

Blood is spun to separate plasma and red blood cells.

Transfusions are also an expensive procedure versus the economic cost of a lamb. However, I’ve found more people raising lambs to keep as forever pets who want to give their animal the best start. It’s a complex procedure. Harvesting is done once a year, from a special group of sheep to ensure antibody levels in the plasma are as high as possible.

HOW TO HARVEST PLASMA

It takes 12 weeks to prepare the donor ewes. I use healthy, non-pregnant, middle-aged ewes who grew up in the region, so they’re likely to have encountered the predominant disease challenges in the area. Middle-aged animals have robust immune systems because they’ve been exposed to a wide range of bacteria and viruses throughout their lives.

The ewes are also vaccinated against several common diseases. Blood is taken when antibodies are at peak levels. On the day of donation, each ewe has a thorough exam to make sure she’s in top health. We remove 450ml of blood from each one, then take it straight to a laboratory for processing.

The blood is spun to separate the different components into two layers:

• red blood cells at the bottom;

• all the immune cells (antibodies) at the top sitting in a clear, slightly yellow liquid (plasma).

Lamb-sized doses can be stored frozen for up to a year. If a vet doesn’t have access to plasma, it’s still possible to help a young lamb, calf or kid. They can draw blood off a healthy adult animal of the same species, then add an anticoagulant and sit the bag upright overnight. However, it will have some red blood cells in it, and it’s a much smaller volume of plasma.

HOW TO ADMINISTER PLASMA TO LIVESTOCK

A lamb, kid, calf or cria has a cheap, simple blood test to measure antibody levels in the blood. If the numbers are too low, we know it’s immunocompromised and will be prone to illness.

Injection

Plasma is injected into the abdomen, where it’s slowly absorbed. To inject in the correct place and not hit any organs takes some skill and understanding of the anatomy. It’s a quick technique, but once the plasma is in their body, if the animal has an adverse reaction, it’s difficult to help it.

Drip

The safest method is to hospitalise the baby and put them on a fluid drip. This way, we can monitor the animal closely for a reaction and stop the drip immediately if anything goes wrong. We can also test the blood again and give a second dose if required.

HOW DO YOU KNOW IF A BABY HAS AN INFECTION?

These are the parts of an immunocompromised animal’s body that are commonly affected by infection. Tip: people often think of infections as causing hot fevers, but baby livestock are just as likely to get very cold.

Joints

Hot, swollen, often in multiple joints, usually the knees at the back or the ‘carpi’ (the middle of the front legs). Sometimes, instead of swelling, the animal will be stiff or have difficulty standing and walking.

Navel

The umbilicus/belly button is a common place for bacteria to enter the body, so you may notice the area becomes hot, swollen, and/or begins weeping.

Blood

If bacteria take hold in the bloodstream, the animal will become septic, weak, lethargic, and cold.

Pneumonia

Coughing is never normal in ruminants and usually indicates a bout of pneumonia.

Spinal abscess

Bacteria may lodge in the spine, but signs aren’t obvious until the lamb is older. When it becomes noticeable it’s because an abscess has become so large, it’s pushing on the spinal cord, which quickly paralyses the back legs. If you notice any of these signs, the animal needs urgent veterinary attention and high doses of the correct antibiotic. If a young animal is weak, cold, lethargic, or has stopped drinking, it may need urgent supportive care to save its life. Again, call your vet immediately.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.