A Lake Wakatipu gardener combines whimsy and nature to convey his big dreams for the world

Born in Switzerland, where he worked as a forest ranger, Thomas Schneider’s whimsical approach to the significant issues of the day results in a profusion of sculptures and statues, flowers and trees, animals and birds, and all critters — great and small.

Words: Claire Finlayson Photos: Rachael McKenna

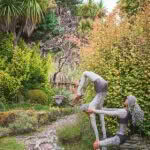

There’s a lavish horticultural hooley afoot on the shores of Lake Wakatipu. The venue is an otherwise tranquil spot between Queenstown and Glenorchy called Wild Dream Garden. It’s a place where bugs and weeds are as welcome to let down their hair as flowers and birds, where the air throbs with a thrilling soundtrack called biodiversity. The host is Thomas Schneider, a former Swiss forest ranger with a deep love of promiscuous, untamed flora.

Thomas didn’t mean to end up in this corner. When he left Switzerland 38 years ago for a year-long overseas adventure with his girlfriend, New Zealand was just a two-week stopover destination en route to Australia. But when that big, parched land failed to impress, the pair headed back to Aotearoa. Once here, transport proved tricky. “We found one old three-speed bicycle but couldn’t find a second one, so I rode a horse instead.” By wheel and hoof, they got the measure of the land and its people and decided to emigrate.

Stepping through one of Thomas’ stone circles is like going through Alice’s Looking Glass and finding other ways of seeing the world. This circle marks the 45th parallel and leads into a garden where more questions are asked than answers given. Its main invitation is to consider overpopulation, something that greatly concerns him. “Every year, we have 80 million more people.” One of his sculptures illustrates how close the population of each country would need to stand to reach the equator (e.g. India — chest to chest; Aotearoa — more than a metre’s length apart).

After a decade of peripatetic farm work, Thomas bought two hectares of land on the shores of Lake Wakatipu that were barren but for a few lonesome gum, beech and fruit trees and an old homestead. “It was always my dream to have a big farmhouse with lots of land, animals, trees and gardens.” Having parted ways with his girlfriend, Thomas put all his energy into creating a haven and planted a mix of ornamental, native, fruit and nut trees. He introduced animals to graze his land and add some life to the place (cattle, lambs, piglets, chooks, geese, ostriches and emus).

“It was like creating a little family. I also thought interesting animals might attract interesting people wanting a place to stay, bringing me some income. I wanted to be self-sufficient. Back then, there was a gravel road to Queenstown. A lot of thought had to be put into compiling a shopping list to make the tortuous trip worthwhile.”

- A bucolic scene of rose-covered arches, strutting peacocks and waddling geese, and a lush spring-fed pond with a water lily-shaped fountain spouting prettily is followed, just around the corner, by what?

- Yes, it is a mighty battle between pre-historic apex predators, the extinct haast’s eagle (wingspan of three metres) attacking the extinct moa (height of three metres) and a child warrior trying to help the moa save its nest of giant eggs. What is Thomas saying here? “Just because we’ve reached the top of the food chain does not entitle us to terrorize everything around us. Just look how respectful the whales, elephants and lions are.

- Thomas taught himself how to create sculptures by trial and error. “With energy and passion, you will see whatever you are building grow, and good things will take time. Our species is focusing too much on destruction and not on enjoying the simple way of life.”

Those interesting animals became less so when they started feasting on things Thomas was trying to nurture. “I had to protect every tree with posts and netting — it looked ugly.” His mammal charges were pretty needy, too.

“For seven years, I felt guilty walking away from my animals to go away with friends. I became a slave to their welfare. Once, when I was on the West Coast for a couple of days, the highland cattle went on a rampage, eating some of my favourite flora. So I decided to let go of the mammals. It was painful, but it gave me more freedom, and I didn’t have to worry about the trees getting eaten.”

There’s still plenty of animal life there today, just the less gluttonous kind — geese, chickens, ducks, a pride of peacocks that catwalk the property, shimmering their tails at the demure peahens. “They do a good job of eating the grass and clover. Without my birds, I would not be able to maintain the garden as it would be too much work.” In the absence of hungry hoofed creatures, Thomas’ garden has enjoyed nearly three decades of rampant growth. There are no manicured edges or orderly lines at Wild Dream Garden — just 700 metres of higgledy-piggledy tracks that weave through abundant vegetation.

- Thomas has calculated that if he were as strong and clever as a spider, he could build a web 68 metres in diameter, and if he were really as brilliant as a spider, he’d do it overnight and from within his own body. “Unfortunately, every generation is getting a bit more disconnected from nature, so the first thing in many people’s minds if they see a spider web is a spray can”.

- Grapevines provide natural umbrella shelter, and under them, Thomas built stone tables and stools for visitors to rest.

- Another upside-down creature, framed by some of Thomas and Christy’s countless roses, is a nod to the flexibility of some human bodies. “Christy and I are always impressed by how flexible some people are, so I decided to show this to our visitors by creating sculptures.”

- The little boy’s bow was made by drilling holes in flat stones and then pushing a steel rod through to connect it with the main sculpture. Thomas enjoys working with natural materials and says this work reminds him that water is a significant part of the circle of life.

Thomas is a gardener of extraordinary largesse: “more is more” under his watch. Come spring, there are 40,000 or so daffodils, thousands of lilies and roses, and a riot of delphiniums, foxgloves, poppies and snowdrops, to name but a few. “It’s not just for the eyes but also the nose and ears,” he says. “If there’s no wind overnight, the whole place is perfumed from the scented flowers in the morning, and hundreds of birds are singing.”

He likes his nature un-medicated. There’s not a whiff of glysophate in the Wild Dream Garden air. Weed advocate Wayne W Dyer famously said: “The only difference between a flower and a weed is a judgement.” Thomas agrees. “A weed is perhaps just something we don’t know enough about. The more you know about it, the more interesting it gets, and then to classify it as a weed is almost not fair anymore. When you take a close look and change the way you view them, some of them are quite cute and useful.”

When asked how he treads the line between a happy marriage of flowers and weeds and unruly garden chaos, he says, “it’s almost like playing God — deciding who is allowed to stay and who has to go. If weeds are pressuring a plant, I might pull them out, shake them and leave them there. Then they become ground cover and rot away and feed the other plants.”

The giant himalayan lilies constantly amaze Thomas and his wife, Christy. He transplants bulbs each year and now has thousands throughout the property. “The tall stalk is to allow the seeds to catch the wind to spread the species as well as multiply by building new bulbs.”

He’s as generous a host to mini-beasts as he is to weeds. The global decline of nature drives his clarion call for urgent biodiverse efforts. “Because we humans have reached the top of the food chain, we believe this planet belongs to us. But I believe this insect and even that weed wish to be alive just as much as we do. We have this lush planet, and we’re not doing the best job of looking after it.”

This stewardship of Earth started early. “When I was a boy, I connected with any creature that could crawl, jump, fly or swim. I didn’t play with a box of toys in the sandbox — I used it to grow weeping willows from cuttings instead.” Thomas was also shaped by the forest-minded country in which he grew up. Trees cover about a third of Switzerland, and the preservation and distribution of woodlands are protected under a forest law about 140 years old.

- The acrobatic bathers illustrate how Thomas believes every action has a reaction, and this couple shows energy held in balance.

- Thomas wasn’t thrilled with the rather boring exterior of his house, so he added a façade of schist and stacked wood and topped the iron roof with a thatch of cabbage tree leaves. The more he worked on it, the more he liked it — and the simple materials reflect his philosophy. “In today’s society, we’re told to make ourselves happy by consuming — buy this, buy that, and you’ll be successful and happy. But when you live out here, you can enjoy little things — like lilies pushing out of the ground. Every time of the year has certain sensations that give you the satisfaction and energy to continue.”

- There’s joy everywhere in Thomas’ garden and, here, a sculpted woman wearing a large sunhat swings a child around her in play.

- Thousands of daffodils and jonquils of all types appear cheerfully every spring. The lake and steepness of the site provide frost protection, with the proof being the profusion of fruit on the mulberry tree.

“When I first moved to New Zealand, I thought that with my knowledge as a forest ranger, I could help ‘green-up’ this country. I even wrote proposals to the government about getting the air force to drop seeds during their training flights. But I was naive.” Realizing that greening-up New Zealand might be too Herculean a task for one Swiss man, Thomas decided to focus on making his own corner as verdant as possible. “I try to live a little dream here — to live in some sort of harmony with the land and not do too much damage.”

Wild Dream Garden is more than a plant-fest, though. There’s an eclectic assemblage of Thomas-made art and installations throughout the garden, including an eight-metre-high staircase that spirals around a gum tree trunk, sculptures created from wire, metal and concrete, and big slabs of stone inscribed with sobering facts and figures about the human-wrought toll on our weary planet. He added these to draw more visitors to the paid-entry garden.

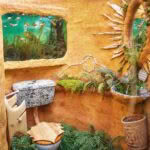

It’s not just the garden that bears Thomas’s creative imprint. Every inch of Little Paradise Lodge (which sits amid the plant profusion) has been thoroughly Schneider-ized too. “In the beginning, I didn’t like the house — it was all white with a lino floor. But when I put some energy into it, I started to like it.”

- Walls are embellished with stones, pebbles, leaves, wood and sand, and even the toilet has a message. “I try to remind people to respect water as it flushes away our waste. So I reversed the usual water flow to reuse water used for handwashing as cistern water.”

- Meanwhile, goldfish float gloriously free and safe from flushing duties.

- And the little starling on top of Christy’s head? “Dupdup fell out of a nest four years ago, and we raised him. He’s like a family member to us. We sometimes call him our stress-reliever,” she says.

- Thomas cut slices of beech tree and jigsawed them together for the lodge floors. He also built the furniture.

- “The Swiss have a deep connection to the forest — it’s almost like a religion. You can’t just cut it down because you have a hole in your wallet. You need to have valid reasons and permission. Forestry in Switzerland is about biodiversity, water, erosion and, at some stage, raw material. A cut forest always must be replanted.”

The resulting lodge décor is a heady mix of heavily mosaiced surfaces, toilet-tank aquariums (where the goldfish get a gentle aquatic wave with every flush) and hand-hewn wooden furniture. It’s full-throttle colour and whimsy — as busy and diverse as the surrounding garden. “When visitors say it’s charged them up or inspired them, it gives me pleasure.”

After nearly three decades of nursing plants, cosseting insects, ministering to mulch, and silencing things white and lino, this baron of biodiversity wants to slow down and, well, actually smell the roses. Tell that to his never-idle hands. littleparadise.co.nz.

THOMAS’S PLEA TO KIWI GARDENERS

“I’d like to encourage Kiwi gardeners to get involved in enriching the biodiversity around us. Every day, we turn more land into plantations, pasture and concrete. Every day, we’re losing a bit of what makes this planet so special. But individuals could try to turn their gardens into little havens for biodiversity and learn how a healthy ecosystem works.

“Imagine a competition among gardeners where, instead of having the tidiest lawn with no weeds, it could be the opposite. People would start to search for all the different lifeforms rather than looking for weeds to fight. You’d get points for each plant and insect species (and additional points for food-producing vegetation and native life forms you discover in your garden). Sterile gardens would most likely lose you points.

“The whole family could be involved in this sort of challenging, educational, environmental competition. Working with nature is a healthy way to keep our bodies and minds in balance. To watch, listen and observe what nature has to offer is satisfying and necessary if we want to learn how to preserve it for future generations.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.