Food for thought: Meet the ancient reflex that can cause overeating when you’re full

Why do we overeat? New research shows the body is at the mercy of two mechanisms when faced with food — hunger and opportunity.

Words: Dr Roderick Mulgan

The issue of weight is common in healthy-eating literature. The majority of us have too much of it, and there is no shortage of official sources pointing out the problem. Until recently, most people had trouble getting enough to eat. Humans throughout the ages have struggled to get enough calories to survive, and loaded tables have usually been the preserve of the elite.

Those days are gone, and the supply chain is now dominated by technology and big money. Even cabbages and carrots are grown in operations of enormous size to supply the nation’s dinner tables in reliable year-round quantities. Dozens of other vegetable and animal staples are the same. Mostly, food is no longer insecure in the developed world. We have the opposite problem: there is too much. What does one do when food is abundant, constantly coming down the pipeline, cheap and easy, begging to be uplifted and consumed?

The question is not academic. Human metabolism has long developed mechanisms for holding onto energy when it is eaten, as storing energy between crops or successful hunts was the only way people used to survive. The currency of energy is fat, the white stuff that packs itself around thighs and abdomens.

Fat stores kept our ancestors alive over winter, and their genes have passed the same tendency to us — so much so that our systems don’t just make their own energy stores but instinctively seek them out. Any chef will tell you that roasting potatoes in duck fat, pouring oil on lettuce, or spooning clotted cream on strawberries turns the dial on diner satisfaction. These practices — and many variations — have long since become embedded in food culture. The unspoken imperative is eating energy, and most of us overdo it because we can.

Illustration: Anna Crichton/NZ Life & Leisure.

Unfortunately, the process is not benign. Excess weight has consequences. When a person overeats, the energy gets diverted into fat stores, and fat stores do not just lie there, waiting until the day they need to be burned. Fat stores stir things up. Fat cells bulge when they are overfull, which stresses them and attracts the white blood cells of the immune system.

Stuffed cells can outgrow their blood supply and die; the debris drives the immune reaction further. Fat cells also make inflammatory modulators called adipokines. All of this creates permanent low-grade inflammation that spills into the bloodstream and affects organs body-wide.

Fat is not just an energy dump. It is a source of deeply unhelpful pro-inflammatory stimuli that affects everything. Heart attacks and cancer have their roots in inflammation, and too much fat tips things the wrong way.

Which raises the question of why we overeat. We no longer wonder where our next meal is coming from. Why can’t we just modestly eat what satiates the hunger for our immediate concerns and move on? Researchers have recently homed in on an insight that answers that question and likely resonates with most people who have struggled with their weight.

It turns out that we do not just have one mechanism that tells us to eat. We have two — two different ones, and they respond to different cues. One mechanism is centered in the hypothalamus, a small but vital structure at the base of the brain that operates the well-known mechanism of hunger. It notices blood sugar levels and how full the gut is. So far, so good.

Hunger is what makes us eat, and we know we have had enough when it has gone. Or we should. But above the hypothalamus, in the midbrain, researchers have discovered another cluster of nerve cells that can tell the hypothalamus what to do. They do not react to hunger or lack of food; they respond to opportunity. It is there, so take it. That makes enormous sense.

In a world of uncertain food, you shouldn’t walk past the injured antelope or the bursting blueberry bush just because you killed something this morning. Opportunity overrides the temporary full stomach. Cram it in if you can.

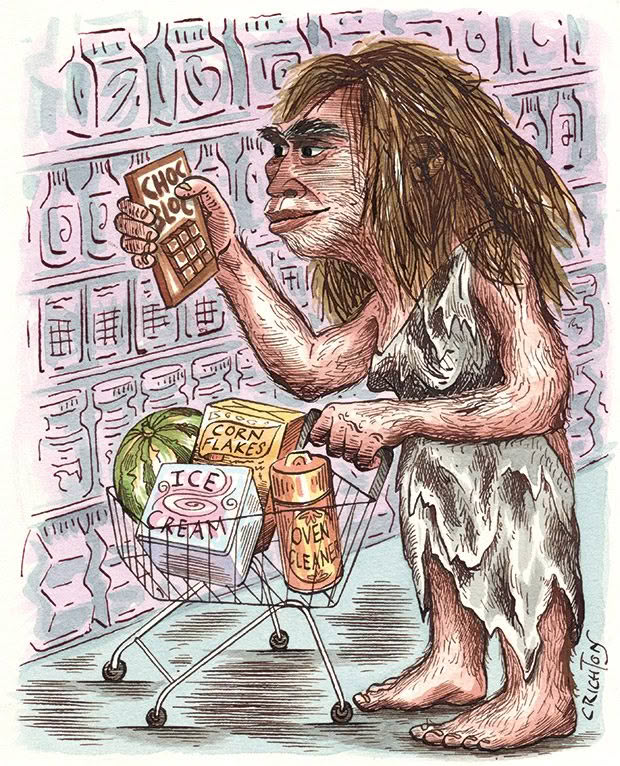

This newly discovered centre explains why biscuits and finger food are routinely offered for light refreshment when nobody is hungry. They promote wellbeing by fulfilling a need that was never about hunger. That also explains the puzzling way people interact with big retail. By which I mean the well-known experience of going to the supermarket for oven cleaner and coming home with corn flakes, a bag of pineapple lumps and a watermelon — because they were there.

People who run supermarkets may not have degrees in neurobiology, but they know this stuff. Their clientele does not have to be hungry to buy something — they just need the opportunity, and big retail’s business model creates opportunities in spades. People with spreadsheets and whiteboards undertake detailed analysis to decide which products get offered at eye level so that customers grab them when they see them, and which get placed elsewhere so that customers have to look for what they wanted in the first place.

And the aisles are not the end of it. Once someone has run the aisle gauntlet and collected those pineapple lumps, the sand traps wait at the checkout. There is no choice about passing through, so that is where the chocolate bars are. It is all an orchestrated appeal to inner yearnings, which have evolved over millennia to snatch opportunities when they present.

So the next time you reach for the chocolate biscuits because they are there, remind yourself: this is an ancient reflex that has nothing to do with what you really need anymore. Knowledge is strength and knowing why you do it is the first step in deciding not to.

ABOUT DR RODERICK MULGAN

Roderick Mulgan has been a doctor for a quarter of a century and has a particular interest in how lifestyle choices affect wellbeing. He is also a practising barrister and the author of The Internal Flame.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.