Case study: How a maternity bra helped give Rose the ewe an udderly happy life

A sweet ewe gets fitted for her first baa bra after an udder disaster.

Words & images: Dr Sarah Clews, BVSc

Who: Rose, 3 year old ewe

The Problem: Rose is a Romney ewe who lives in a small flock of beloved sheep. Her owner intended for them to live a happy, lamb-free, easy-breezy life on their block, south-east of Auckland. But when a neighbour’s determined ram found his way through the fence, Rose got pregnant.

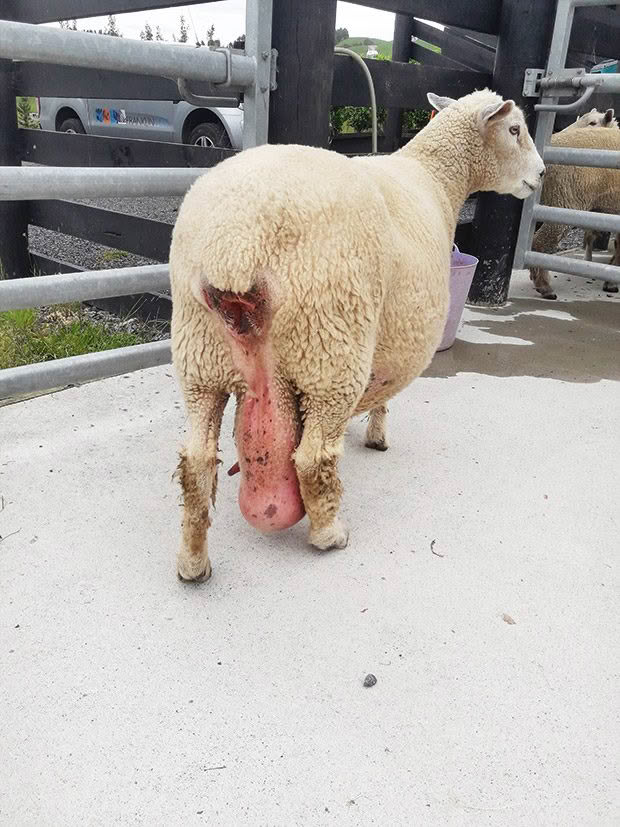

All went well, and Rose gave birth. However, a couple of days later, as Rose’s milk production increased, her udder suddenly and dramatically changed shape. Rose could barely walk, let alone feed her lambs who were now squabbling for teats that were almost dragging on the ground.

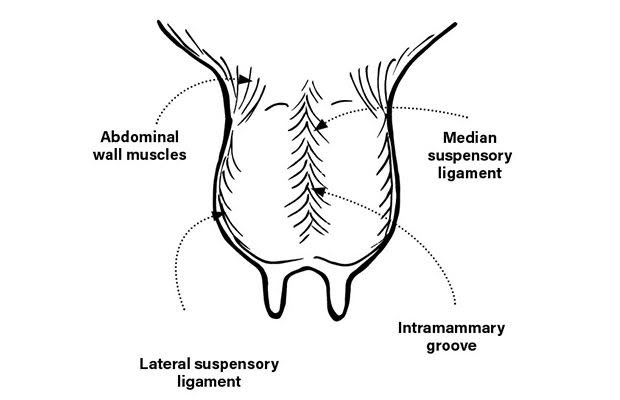

The Investigation: While Rose and her lambs were in otherwise good health, her udder had suffered an acute rupture of its suspensory ligaments. In animals such as cattle, goats, and sheep, the udder hangs from the body, suspended by two sets of ligaments:

■ strong, fibrous, ligaments that run down the outside of the udder

■ flat, sheet-like ligaments that run through the centre of the udder, separating its left and right halves.

The ligaments inside are very elastic, stretching to allow for the additional weight of the milk. They’re so strong that you could remove all other supportive structures from the udder and they’d still hold it in place. However, sometimes the weight is just too much, and they overstretch.

Rose’s udder disaster. Her teats were almost dragging on the ground, making it very difficult for her lambs to feed.

It’s called a ‘dropped udder’, and vets mostly see it in older, high-producing dairy cattle. Despite the obvious discomfort of damaging major ligaments, there are other issues. The udder and teats are at high risk of:

■ injury, from dragging on the ground or from being stood on by the ewe;

■ bacteria getting inside the udder, resulting in mastitis.

A tell-tale sign of damage to these middle ligaments is that the teats will point out to the side. That also makes it tricky for lambs to get a drink. The conformation of the udder and teats, the strength of the ligaments, the amount of milk a mother produces, and the number of lambs she carries (which determines milk supply) are all influenced by genetics.

Rose got a bad batch, and that meant her lambs could develop the same issue. Farmers usually cull ewes that suffer from this type of ligament issue to remove these genes from their flock. Rose wasn’t meant to have lambs, so it wasn’t an issue for her owner.

The Treatment: Animals with a dropped udder are often euthanised, unless an owner is willing to support the ewe and care for the lambs. Fortunately for Rose, her owner was keen to help. Overseas, there are breeds of cattle that produce extraordinary amounts of milk from truly enormous udders. Farmers buy ready-made slings to support the udder during the milking season.

We don’t have them in NZ, so we improvised. Her owners finally found a 24J Rose & Thorne maternity bra, which the company donated (and where Rose got her name). Rose received anti-inflammatory pain relief, and we fitted her baa bra with holes cut for her teats to poke out. Her owners had instructions to watch that the lambs were managing to drink and that the bra was sitting comfortably. They also had to regularly check for signs of mastitis, and treat it promptly if it occurred.

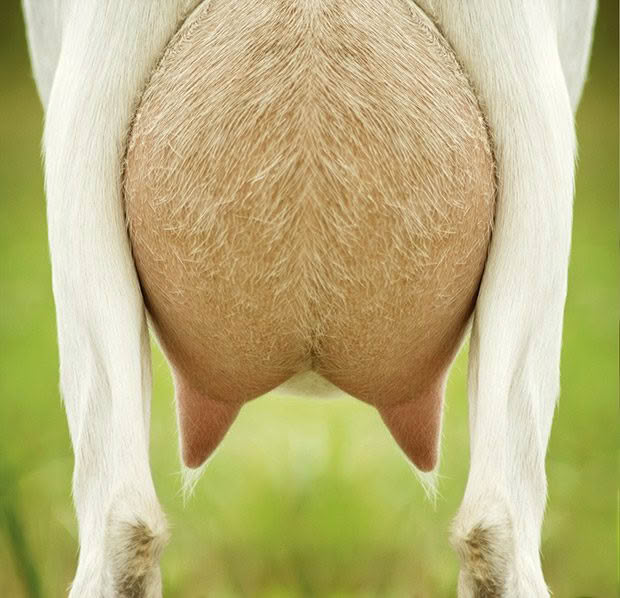

Rose & Thorne donated a 24J maternity bra, and Rose was named in their honour.

A ewe’s milk supply peaks 2-4 weeks after lambing, so Rose didn’t need to wear her bra for long, and she happily fed her lambs. When the bra was removed, her ligaments had retracted, and she was on her way to a full recovery.

Many animals aren’t so lucky. Often the udder remains ‘dropped’, depending on the damage to the ligaments. If things hadn’t worked out, options included:

■ bottle-rearing the lambs, allowing the udder to dry off;

■ a mastectomy (surgical removal of the udder);

■ euthanasia.

Rose hit a running streak of luck at every turn. Her dedicated owners, early treatment, and no more babies mean she’ll get to live a long and udderly happy life.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.