How to find the balance between healthy foods and palatable flavour

It’s all very well for the strong-minded to advise ‘food be thy medicine’, but what if it tastes awful and has the mouthfeel of shoe leather? Unfortunately, many of the best things do. The way to palatability can be through a marriage of convenience.

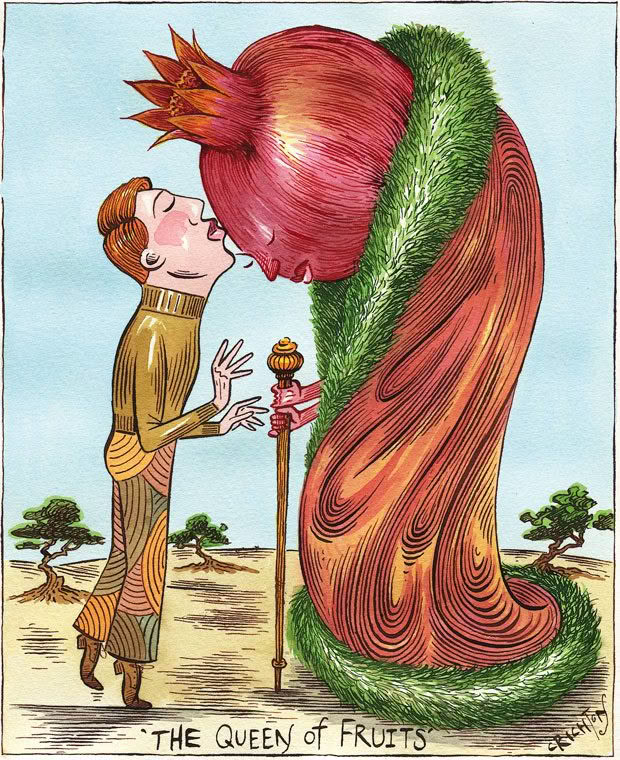

Words: Dr Roderick Mulgan Illustration: Anna Crichton

One of the themes in healthy food is nutraceuticals. These polyphenol molecules, made by plants, tickle the metabolism in healthful ways.

Regularly eating fruit and vegetables, as all good-living guides advise, means you probably already consume some. Surveys of the general population’s intake of fruit and vegetables regularly deliver depressing results, which means there’s room for improvement.

Regardless, it is imperative to seek out rich and novel sources of polyphenols and maximize their intake. There are dozens of options. An excellent place to start will win me many friends — chocolate.

One of the natural world’s richest sources of a family of polyphenols called flavonoids, chocolate is not the fat-filled mouthful of smoothness that has given its vibe to Valentine’s Day and ultimate moments of indulgence. It is a bitter-tasting drink and only popular because so much is done to modify its natural properties.

First among these is sugar, the factory-food world’s ubiquitous answer to any awkward taste sensation. Sugar is not just sweet; it is a mask for other things and crops up in all sorts of unexpected places, such as tomato sauce.

Chocolate goes well with sweet sensations, so there is no need to obfuscate: lay on the sugar and call it a sweet treat. In fact, many experiments have been done to find marriage partners for chocolate that make it palatable.

Good chocolate lowers blood pressure and makes platelets less sticky, and therefore less likely to cause a blood clot.

In addition to sugar, milk powder has also stood the test of time and is where the term “milk chocolate” comes from. But chocolate’s pitfalls are not limited to flavour companions. Modern chocolate’s multiple processing steps from the tree to the foil-wrapped bar reduce the polyphenols tenfold, which is what they are intended to do.

Retailers succeed by appealing to what tastes good, not what is best for human health. Yet, the benefits of good chocolate are worth finding.

Good chocolate lowers blood pressure and makes platelets less sticky, and therefore less likely to cause a blood clot — which can prompt strokes and heart attacks. It dampens down the unhealthy inflammation that lies behind life’s big diseases. It may even fend off diabetes, which is not a common outcome of eating confectionary.

These benefits are available from eating the right type and easily reversed if people overeat the wrong type. The right type is the type called “dark”, but caution is required as the term is overused.

The real test is the percentage of cocoa solids, which any worthwhile label will state; anything more than 70% is a health kick (in moderation, of course). Also available is lightly processed chocolate powder. This is called cacao and available for marriage partners of your choosing. My suggestion — and personal practice — is with fruit in a smoothie.

Pomegranate is another rich source of polyphenols and particularly noteworthy for suppressing the risk of cancer. It doesn’t crop up often in the average diet, but it is a standout example of the nutraceutical concept.

It is also an example of how the goodness in plant food doesn’t just reside in the edible bit. Like olives and avocados, pomegranates have become a health trend in recent years and are easy to find.

They can even be grown by those living far enough north. The edible bits are the ruby red seeds inside, but most of the health-giving polyphenols are in the skin, which is about as palatable as shoe leather.

The main polyphenols are ellagitannins, particularly a large one called punicalagin, which doesn’t occur anywhere else. Consequently, the best bit of the pomegranate is arguably the juice, which comes from the whole fruit.

Once again, some compromise with the taste of the raw product is unavoidable, but the options need research. Sugar plays its usual role at the cheap and unquestioning end of the market, and the resulting product is little more than cordial with pomegranate flavour.

Likewise, juice made from concentrate is unlikely to retain much of the fruit that it started with. My personal preference is a juice that has been pasteurized; the heat treatment kills enough of the bitterness to make it drinkable, and nothing else needs to be added.

The skin is also the polyphenol focus for berry fruit. Small fruit has a large ratio of skin to volume, so skin constituents dominate when they are eaten. Any wine connoisseur can talk about the role of grape skin in their tipple — thin and delicate in pinot, thick and robust in cabernet — and the principle holds for all small fruit.

This may well be because the plant makes polyphenols to protect itself from outside threats, such as UV light, which must be concentrated at the surface. The standout berry polyphenols are anthocyanins, making berries blue and red and, by happy coincidence, providing potent antioxidant activity in people who eat them.

Berries appear to contradict the observation that metabolically beneficial polyphenols are bitter. But berries and fruit evolved the same trick as chocolate-makers.

They mask their bitter notes with fructose, the sugar of fruit. Which does not mean you should file fruit in the same mental category as confectionary. The balance between sweet and healthy is much more favourable in something you eat in its natural configuration, and no self-restraint is called for.

MORE HERE

What are nutraceuticals? Meet the healthful compounds found in every superfood

How silent inflammation can affect health outcomes later in life

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.