Case study: How Snowflake the goat kid overcame a bad case of pneumonia

Taking a sick animal out of hospital and into the sun seems to help them perk up (once they’re out of danger).

Country vet Sarah Clews meets goat kid Snowflake during his hospitalization from a bad case of pneumonia.

Words: Dr Sarah Clews, BVSc

Who: Snowflake, 3-week-old goat kid

The problem: Snowflake’s owners were raising him for their local school ag-day. They brought him into the clinic when he developed a roaring fever, a snotty nose, crackly-sounding lungs, and became dull and lethargic.

THE INVESTIGATION

We treated Snowflake for pneumonia as an out-patient, but I warned his owners if he showed any signs of decline, such as refusing a bottle, he would need hospital treatment. Pneumonia is a taxing disease for anyone, animal or human, as there’s not enough oxygen getting into the bloodstream.

An animal is less likely to eat when it has a fever. As a baby, Snowflake’s waning appetite put him at high risk of hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar). The most likely cause of his pneumonia was aspiration of a liquid, probably milk.

THE TREATMENT

Snowflake initially received antibiotics and anti-inflammatories to help with the pain and reduce inflammation in the lungs. But a few hours after he went home, his owners noticed a big decline in his strength, he started developing neurological signs, and they rushed him back to us.

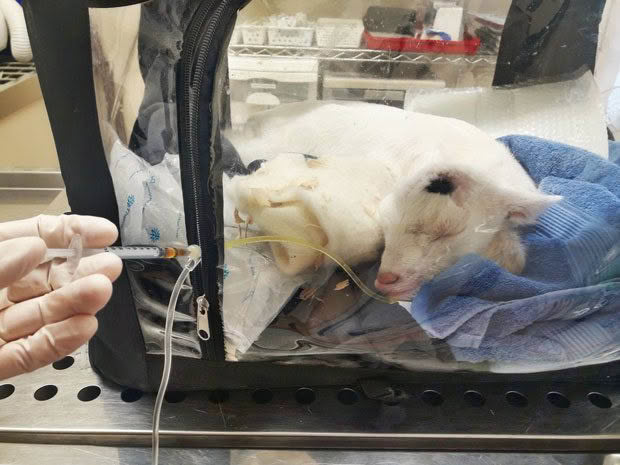

Snowflake receiving medication to help fight the infection.

You will often hear farm vets say that if a sick baby animal stops drinking, it’s very difficult to get them back to full health. I’d amend that to say hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) and metabolic problems set in, making it difficult to get them back without hospitalisation.

By the time I saw Snowflake again, he was so weak he couldn’t stand. His breathing was fast and shallow, and his fever had gotten worse. Most concerning was his odd neurological behaviour: strange neck stretches, ‘star gazing’ up at the ceiling, apparent blindness, and poor reflexes. A malfunctioning brain can be caused by many things.

Some of the more common causes include:

• a bacterial infection of the nervous system;

• vitamin deficiency;

• genetic anomaly;

• ingestion of a toxic plant;

• parasites.

However, I was sure Snowflake’s rock bottom blood sugar was to blame, confirmed by a blood test and his clinical signs. We placed a catheter into a vein to give instant access to the bloodstream.

He received intravenous fluids to help with hydration, correct his metabolic disorders, and slowly bring up his blood sugar levels. He was also placed in an oxygen cage, an easy way to provide supplemental oxygen to a patient whose lungs aren’t functioning correctly.

THE RESULT

Snowflake spent the next few hours snuggled up in comfort blankets. I sat by his side, giving him a concoction of drugs through his dripline to help him fight the infection and feel better. Within an hour, his brain function returned to normal. I was relieved, as severe and prolonged hypoglycaemia can cause irreversible brain damage.

It was another few hours before he mustered the strength to nuzzle my hand, looking for a drink. He sucked some warm milk from a bottle with a slow-flowing teat, then went back to sleep.

Snowflake in the oxygen cage. It’s a simple way to provide supplemental oxygen to an animal to help with their breathing.

Later in the day, he showed some fleeting enthusiasm and tried to stand. He’d been very good not to soil his bed, so I disconnected his drip and gently carried him outside to the grass. A few wobbly, breathless steps, and Snowflake happily toileted, a relief to both him and me.

I find that taking grazing animals out into the sun, with the grass beneath their feet, often helps them to perk up dramatically. It’s often the turning point for a very ill, hospitalised sheep, goat, calf, or alpaca.

Even though Snowflake was still too young to eat grass, his mood changed dramatically. There was such a big improvement, we let him go home with his owners, with instructions for plenty of rest and careful nursing.

WHAT IS ASPIRATION PNEUMONIA?

Young, bottle-fed animals are most at risk of developing pneumonia after accidentally breathing in fluid. The fluid is commonly milk, but may also be saliva, vomit, or regurgitated food.

In adults, aspiration pneumonia is caused by a ruminant (sheep, goats, cattle, alpaca) breathing in regurgitated food (known as the ‘cud’). It often happens when they’re unwell and lying on their side for a prolonged period or lying with their head facing downhill. They sometimes develop aspiration pneumonia even after recovering from the event that made them lie down.

In young animals, it’s usually a combination of greed and inappropriate teat flow. If milk is flowing freely from the teat end of a bottle (without the animal needing to suck), they can breathe in the milk while taking a breath after swallowing.

MORE HERE

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.