What is fourth-dimension garden design? How Nelson Lebo uses this approach on his 5.1ha permaculture farm

On this block it takes a month to cut down a tree, six months to build a garden bed, and two years to plant avocados, all to save money, effort, & time.

Words: Nelson Lebo Images: Brad Hanson, Nelson Lebo

Who: Nelson, Dani, Verti (8), & Manu (5) Lebo

Where: Okoia, 10km east of Whanganui

Land: 5.1ha (13 acres)

What: permaculture, regenerative agriculture

Web: ecothriftylife.com, theecoschool.net

If I sit for two hours, drinking coffee and thinking, the efficiencies I come up with can easily save me 12 hours of manual labour. The result is that in six years, we’ve transformed a tired piece of land into a thriving permaculture farm on a shoestring budget, with minimal burning of fossil fuels.

It’s not about being lazy. It’s about being mindful, and most importantly, consistent. I see time as an ally rather than an enemy, as many block owners do.

We use a regenerative approach to food production on our block, using what I call four-dimensional design. In physics, time is the fourth dimension. Four-dimensional design focuses on using time to your advantage, saving you effort, money, and fossil fuels, while establishing and operating efficient and regenerative systems.

Nelson Lebo is an eco-design consultant and farmer. He lives with his family on Kaitiaki Farm outside Whanganui.

Designing in four dimensions doesn’t require you to have a fat wallet. It maximises the value of available resources, minimising waste and the need for heavy equipment.

In business, this type of thinking is common. It’s called ‘just in time’ (JIT) inventory or broadly ‘supply chain management’. Industry leaders have determined that the most cost-effective way to operate is to do things at just the right moment and to avoid double-handling.

For businesses, it’s a matter of keeping things in motion. On a farm, it’s to keep up with things already in motion. At times – especially in spring when life takes off – I think of it as ‘inertia management’. Inertia is how matter continues unchanged on its path in uniform motion unless acted on by an external force. On a block, the ‘uniform motion’ is primarily plant growth powered by sunlight.

The key is knowing when you should be an external force and when not to. Following are three examples of how we use four-dimensional design on our block.

Case Study 1: Why it takes a month to cut down a tree

The overarching goal on our block is climate resilience. We believe one of the best ways to achieve that is to plant thousands of trees on its eroding stream banks and slip-prone hillsides.

In both cases, deep-rooted trees, native grasses, flaxes, and shrubs form a riparian corridor that holds soil in place during significant rain events. Those same roots tap deep into groundwater during dry spells, producing high protein foliage for use as stock fodder in summer.

The most dramatic effect of climate change on the farming sector is extreme weather, either too much rain or too little. Part of our holistic response to ‘climate-proof’ our land has been to shift much of it toward tree-based systems for growing food. We pair each system with complimentary animals that we see as workers rather than objects. We value their time more than their flesh.

This approach goes right to the philosophical and linguistic origins of permaculture – ‘permanent agriculture’ – based on robust perennial plants and efficient systems. You might be wondering then why we would cut down a tree? There have been several reasons over the last five years, including:

• trees growing too close to the house, reducing air circulation;

• creating space for an outdoor barbecue and dining area;

• managing tagasaste (tree lucerne) which act as nurse trees for our avocados (see page 16);

• clearing space for a new driveway to a minor dwelling.

We’ve planted 100 trees for every one we’ve cut down. What’s important is how we’ve cut them.

In most parts of NZ, when a tree is marked for felling, it’s because it’s either an asset or a liability, but rarely is it both. On our block, where we strive to get multiple benefits from everything we do, we see trees as both.

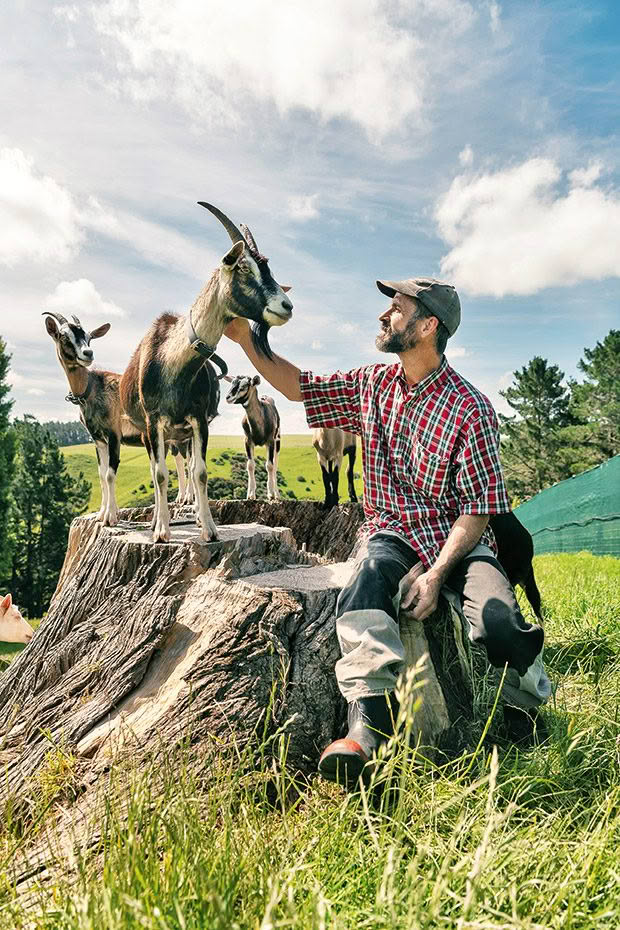

The goats grow very fat on a steady diet of tree branches, producing milk for the family. With help from permaculture interns, they regularly make simple chèvre, ricotta, halloumi, and mozzarella. Dani says they love cheese far too much to be vegan.

A tree that must be felled is also weeks of goat tucker, firewood, and compost, if we take our time to cut it down. Like most food, leaves and branches are perishable. Once a tree is felled, the clock begins ticking. Goats can eat a lot, but there’s only so much they can consume in a day.

As long as the trees or shrubs aren’t toxic, our strategy is to cut 2-3 branches each day and carry them to the goats. The advantages are:

• the job is easy and manageable;

• the goats get a steady supply of fresh fodder.

Cutting and delivering fodder to the goats becomes part of our morning chores, along with feeding the chickens and ducks. The branches are strung along fences as goats prefer to browse than eat off the ground. The goats eagerly strip the branches of leaves, small twigs, and bark.

Depending on the season (and our kindling supply), the stripped branches are directed to the wood store for the following winter, or used to create the base of raised hugel mounds.

This approach has been so successful, we’re now routinely pollarding poplar and willow we’ve planted to protect the stream banks and hillsides. Pollarding is where you prune a tree trunk back to a high ‘stump’ (about head height) over winter. It regrows a bushy, foliage-dense top that’s perfect fodder and easy to re-cut. Even after last year’s drought, our goats remained fat and happy, and the trees were ready to regrow foliage in spring.

The pairing of willows and poplars is a great way to produce nutrient-rich fodder on marginal land, with the added benefits of erosion control, climate resilience, and soil health.

WHAT IS A HUGEL MOUND?

Hugelkultur (‘hill culture’ or ‘mound culture’) is a German word that describes a type of raised bed. Piles of branches form a base (pictured). This is covered with topsoil and/or composting materials if you have them. Water drains through it quickly, helping to rot the wood. The wood releases nutrients that benefit the soil. They also act like a sponge, holding more water as they decompose, which plant roots can use. The wood eventually breaks down, creating new soil.

Case Study 2: Why it takes two years to plant avocados

We’ve planted over 250 fruit trees, including 40 avocados, as part of our tree-based approach to regenerative agriculture. Avocados are a challenge. Among other things, they’re:

• frost sensitive;

• wind sensitive;

• sun sensitive when young;

• unable to tolerate saturated soils.

Nelson sitting on the island with the avocado trees.

All of those conditions exist on our farm. It has taken time – two years plus – to prepare spaces where they can thrive for decades.

Our approach involves protecting them using a technique we learned from friend and horticulture expert Rob Bartrum. He successfully grew avocados in Feilding, which experiences even harder frosts than Whanganui.

He used closely planted tagasaste (also known as tree lucerne) as both an umbrella and blanket for the young avocados. Tagasaste (pron. tag-ah-sar-stay) are hardy, fast-growing ‘nurse’ trees. They help prevent sunburn on leaves during summer, provide frost protection, shelter from the wind, and fix nitrogen in the soil.

Verti and Nelson checking the avocados.

We used this technique on our first (urban) property in Castlecliff 10 years ago while planting a wide variety of fruit trees. The big difference is here we have clay, compared to the free-draining sandy soil at Castlecliff.

We’ve had to apply two distinctly different techniques to prevent waterlogging – mounding and draining. We created a ‘rubble road’, which acts as a solid walking surface and allows water to drain away from sheds and trees. Then we built an ‘island’ for the avocado, a mound of soil roughly 8m by 3m, well above the seasonal high-water table.

- Broken bricks help to create a free-draining planting area. This photo shows the tagasaste, just before the avocados were planted.

- Nelson created a ‘rubble road’ using broken pieces of concrete. It’s also a drain, channelling large amounts of water away from the buildings, and the ‘island’. Plum trees grow on a swale, which also helps to drain water away.

- Normally, the kune kune pigs graze under the fruit trees because they’re the only stock that keep the grass down, but don’t browse the trees. However, Nelson has now shut them out of this area while the second planting of tagasaste is establishing.

We piled old bricks from a friend’s chimney around it to help with drainage, just before we planted the avocados. Opposite the island (to the left of the rubble road) is a swale, which also holds water and is planted with Sanguine (Black Boy) peaches. We now harvest Hass, Reed, Bacon, and Sharwill avocado varieties, all grafted on Zutano rootstock.

THE SECOND AVOCADO ORCHARD

The avocado island experiment proved successful, but it’s limited by scale. To establish a more commercially viable orchard, we selected the only spot on the property with free-draining soil, a small shelf above a stream, 100 vertical metres below our home.

However, soil conditions alone weren’t enough. We dug surface drains between the rows and used the soil we dug out to create mounds, so the tree roots sit slightly higher.

Another drawback of this spot is cold air settling in the valley and associated frosts. To protect the avocados, we propagated and planted 200 tagasaste. Hungry hares promptly ate 190, so I’ve recently replanted more and used shade cloth for frost protection.

Case Study 3: Why it takes 6 months to build a garden bed

I have a background in small-scale market gardening in the USA (where I was born) and have learned to deal with a lot of couch and kikuyu grass in NZ. It’s an endless struggle if you have perennial weeds in annual gardens, and vital to eliminate them when you’re establishing new beds.

I don’t believe in rotary hoes or the manual turning of soil but I do believe in time. Building garden beds takes six months because that’s how long it takes to kill off most perennial weeds under plastic. We use heavy builder’s polythene, the same grade required for groundsheets under homes. We then lay mulch over the top to protect it from UV damage. That way, we can use the same sheets over and over again to build new beds or reclaim beds where buttercup has gotten out of hand.

The rest of the process takes one day and involves broad forking the soil to create blocks, then breaking it up to form a bed. You can watch us building one on our website, ecothriftylife.com – search for ‘building beautiful beds’.

Managing the beds and paths is a matter of time or more specifically, timing. “Once a week, every week, on a sunny, windy day,” is my mantra for stirrup hoeing annual weeds before they become established. While this approach will be familiar to most market gardeners, the way we maintain the paths between plots probably isn’t.

In spring, Nelson uses a scythe to control the grass as it grows too fast for their chickens to graze it.

Rather than using a mower or trimmer, I prefer chicken tractors and the timely use of a scythe. For most of the year our chooks happily cut and fertilise the grass in between the beds, while also producing eggs. But in spring, they can’t keep up with the flush of growth. That’s when I sharpen the scythe and harvest mulch. It’s then applied directly to the beds to reduce evaporation in summer or to cover the polythene.

- Hoeing annual weeds into the soil.

- Thick, black sheets of polythene kill off perennial weeds when it’s time to create a new bed.

This is a micro-scale example of regenerative agriculture. The chickens produce food (eggs) and help to build soil fertility with their manure. When we clean out their tractors, we put the manure into our compost. When the grass is too much, we hand-harvest it and use it as mulch. The grass feeds the chickens, the chickens feed the grass, and both feed the garden beds nearby.

Designing and managing synergistic systems like these is a matter of timing. Get it right, and everything flows; get it wrong and you’re mired. Time waits for no one.

WHO ARE ‘WE’?

Establishing and managing a low-carbon regenerative farm relies on people and animals rather than machinery. In this article, ‘we’ refers to the collective effort of a steady stream of permaculture interns who have worked alongside us over the last six years. While the design and management decisions are made primarily by me (Nelson), their help implementing them has been invaluable.