How Waiheke artist Tanya Wolfkamp found a unique style with her colourful depictions of Aotearoa

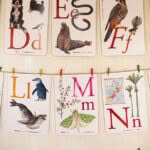

Artist Tanya Wolfkamp with a line-up of her alphabet illustrations.

On a hillside on Waiheke Island, an artist has found her niche, creating the designs for colourful Kiwiana homewares and accessories.

Words: Jane Warwick Photos: Tessa Chrisp

In the wide storage drawers of Tanya Wolfkamp’s hillside studio are scattered the imaginings of a creative and thoughtful mind. There are caravans and tents, pōhutukawa and nīkau.

There is the letter A for royal albatross and red sea anemone (toroa and kōtoretore), B for Buzzy Bee and red admiral butterfly (pi and kahukura), C for caravan and cabbage tree (whare wīra and tī kōuka) right down the syllabary to Te Riu-a-Māui (Zealandia) and the bright and beautiful little zinnia.

There is a blunder of kererū and an iconic etching of the tangled forests of Aotearoa that look perhaps… well, not quite, but almost familiar.

Tanya particularly likes designing wallpaper murals. She says it’s like tailor-making someone’s dream, whether they want a forest in their hallway, or a crowd watching them drum. Any subject will do. “I don’t care if it’s a rose, a car, an abstract; I don’t care if the subject is not particularly ‘me’, just as long as I have a pencil in my hand.

Tanya reckons she has no clue to a good notion; Max, the cat, rolls his eyes. But Tanya is firm in her opinion that she doesn’t know where to start although she knows she can finish. Looking at her concept drawings, her doodles and her tappings into the essence of New Zealand, the observer would have to side with Max — the artist is underrating herself.

Good artists, however, are always staring into the abyss of their self-doubt, never measuring their worth by anyone else’s standards, but their precarious ego. Perhaps that’s what gives them the edge?

- “If I had been a purist, if I had forced myself to have a specific style instead of getting away with multiple styles, if I had just stuck to painting, I don’t believe I would have the range of skills I now enjoy.

- “In a lot of ways, what I do is just craft. I am a tradesperson.”

Tanya certainly has an advantage despite her misgivings. Her Wolfkamp & Stone brand depictions of what defines New Zealanders can be found in homes nationwide, on linen, tableware, tea cloths, bunting, stationery and personal products.

It is a wide range that offers a broad scope of artistic expression and, in the beginning, the lack of a particular Wolfkamp style made Tanya jittery.

Artists are expected to have a specific character, unique to them, and Tanya’s mind was always so full of what could be done that she couldn’t settle on just one form.

The décor in Tanya’s cottage can only be described as individual as her various projects, from the enamel picnic ware to the design for a carpet seen on her computer screen.

Art school was a bit of a trial for Tanya; she didn’t fit and even then could see her trajectory was different from her classmates. She doesn’t precisely know why; perhaps because she never particularly ran with the crowd as dictated by the curriculum.

It was the 1980s and early 1990s, the height of the feminist movement. There was an emphasis in the arts on socialism, Marxism and deconstructionism.

Tanya was keen on art philosophy and was an avid reader of French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre until one day she opened one of his books and just felt nauseous, and that was that. Nevertheless, she stuck out the five sometimes-bewildering, sometimes-discomforting years and graduated with a painting degree.

She gained a place as a textile designer at Maurice Kain Textiles — then lead by the celebrated Peter Hall, whose work is on show in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum — and this is where she found both her feet and her niche.

Textiles were the ultimate blank and shifting canvas, and at last, she had found something that didn’t demand she stick to a particular style.

It irked her; writers and musicians change styles all the time, but somehow, it is frowned on in the visual arts. At art school, she was at the tail end of being taught to draw — it is no longer a modern art practice — and, oh, how her pencil flew.

- Tanya bought an old trunk full of assorted bronze letters at an auction, gave many away, and then honed her anagram skills to come up with the message above the window. The three “character” cushions on the window seat are named Fed Up, Under Fed and Over Fed, prototypes from a long-ago project.

One day, there were florals; soaring modernist sketchings the next. Botanics, fauna, drawings subdued, patterns exuberant; Tanya got over her hang-up about not having a particular style.

Peter was the first person who really told her how to make something work, the mechanics of painting and drawing. People buy colour, he said. They think they’re buying a picture — and it’s the subject that draws them to it — but, actually, they’re purchasing colour.

So Tanya threw herself into that kaleidoscope of mood and emotion that spills from the seven shades of the visible spectrum, thinking at first that she wanted to design everything in the home, from curtains to plates, to be, perhaps, a sort of William Morris of her generation.

But she laughed herself out of that fit of what she could only call a type of megalomania and immersed herself in textiles and wallpapers. She was so successful she eventually stepped into Peter’s role.

- Tanya’s collection of chairs and Crown Lynn are only befitting a wee Kiwi cottage.

- The curtains framing the French doors are a design Tanya did for the soft-furnishings provider, Hemptech, which specializes in natural and sustainable textiles.

- Max (above) is ever ready to lend a helping paw.

The studio closed and Tanya set out on her own. She had clients who followed her, but she also sent out feelers for new patrons, and Helen Harvey of Live Wires couldn’t believe her luck. Live Wires sources Kiwiana for retail outlets and Tanya’s portfolio and flexibility were just the thing for the company.

It was a turning point for Tanya as Helen has a fearless entrepreneurial spirit. Her ideas come thick and fast, and Tanya says she is a creative genius. Helen would ring with some new concept that would make Tanya chew her lip anxiously and say, “Perhaps these ideas are too disparate?” to which Helen would answer, “Who cares?”

This gung-ho attitude almost invariably led to success, which further encouraged Tanya to care less that she didn’t have just one particular style. (Although she does have friends who reckon they can spot her work a mile off, regardless of how she presents it.)

This then is the basis of Tanya’s depictions of Aotearoa that sometimes look so familiar and then, from the corner of the eye, not quite. She layers ideas and borrows elements of style.

Her dense bush scenes might be based on a scan of an existing print or picture, long forgotten, and then overlaid and introduced with her own drawings of classic New Zealand flora.

- Tanya renovated her bathroom, transforming it from a lean-to to a smart haven.

- The wallpaper mural in the toilet, called Wildscape, was designed for Resene and is due to be released. The prototype of the mural, printed to check for mistakes, is now hanging in the bedroom of her brother Peter Wolfkamp’s villa.

- Peter is Newstalk ZB’s Resident Builder and the site foreman for the television series, The Block NZ.

Her favourite canvas, as it were, is using scans from the book Buller’s Birds of New Zealand, a series of paintings by 19th-century Dutch artist, Johannes Gerardus Keulemans, that are now beyond copyright. Perhaps some of Tanya’s Dutch DNA draws her to them.

So here she is now, in her wee studio, pencil in hand, Max at her feet, on a Waiheke Island hillside. She still maintains she has no good ideas and that Helen is the inspiration behind her sketch pad, but it is a fancy that is increasingly hard for the observer to believe.

- The prints on the wall behind Tanya and her husband Charlie are Charlie’s work, done in ballpoint pen and inspired by the novel, The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov.

- Charlie also built the shelves and sideboard from local timber.

Further down the slope is the small miner’s-style cottage that she now shares with her husband, Charlie.

They finally hooked up after one of those age-long attractions consisting of, at first, startled and then wistful glances because neither was ever at liberty from their current life at the same time. But then suddenly they were, and both of them had the wit to do something about it.

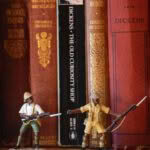

On the macrocarpa bookshelves that Charlie for built her, she has arranged her eclectic library in order of the author’s birth. How is that not an original thought or style?

MORE HERE

Ōpōtiki artist Fiona Kerr Gedson transforms feathers into Nepal-inspired mandalas

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.