How to plan a wetland restoration and learn from those who did it

Learn from those who’ve done it on how to repair and restore a past wetland that can help save the world from climate change.

Words: Rachel Rose

Who: Matt Paulsen

Land: 20ha

Where: Waipukurau, 50km south-west of Hastings

Matt Paulsen is a shearing contractor and keen duck hunter. The wetlands he has re-established have various benefits, but what Matt talks about most is the joy they bring.

“I love the birdlife. Another brood of ducklings are now on the water, my boys (12, 10, and six) love seeing that. It’s so neat to provide the habitat.”

- February, 2017. (Photo credit: Nathan Burkepile, NZ Landcare Trust)

- March, 2017.

- March, 2017.

The hydrology in Matt’s wetland is complex. A shallow dam is fed by groundwater and run-off from the catchment above. The second, connected pond is spring-fed.

“The spring was badly pugged, but once that pugged cap was excavated, it started to flow like crazy,” says Nathan.

Most of the topsoil (stockpiled to one side in the image, top left, from February 2017) was used to line the bottom of the dam before it filled with water. It introduced helpful microorganisms and aided with water retention.

Who: Will & Rose Parsons

Land: 12.8ha

Where: Riverlands, 8km east of Blenheim

Will and Rose Parsons bought their block near Blenheim partly because of its beautiful 8ha wetland. It covers most of their block and drains into the nearby Opawa River.

The Parsons’ block, showing their wetland’s proximity to the Opawa River. Despite a lot of planting, the couple has battled with persistent weeds such as crack willow, oak, and Tasmanian ngaio. The water can be drained and then refilled from an artesian bore, which Will did one year to eradicate an oxygen weed infestation.

The wetland was established by the previous owner, a keen duck hunter who mixed native plantings with exotics, including fruit and nut trees. The Parsons have chosen to remove the exotics and plant more natives. The reforestation offsets the carbon emitted by their business, Driftwood Eco-Tours.

A QEII covenant means the wetland is protected, even under future owners. The Parsons’ say the appearance of rare native fernbirds has been a thrilling reward. The area is now a mature eco-system, which Will describes as “self-managing”.

Who: Ian Moore

Land: 230ha

Where: Lake Rotokare, 50km south of New Plymouth

The deciduous exotics in Ian Moore’s wetland are bright enough to light up a grey day in late autumn. Many landowners and community groups are strongly committed to reforesting wetlands and other areas only with natives grown from seed collected in the same region.

- Wetland: Ian Moore, Whanganui. (Credit: Rachel Rose)

- Wetland: Lake Rotorkare, Taranaki. (Credit: Rachel Rose)

Another point of view values the eco-system functions of exotic trees. Ian’s wetlands include liquidamber, tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica), and pin oaks (Quercus palustris). The tiny acorns of pin oak are a perfect size for ducks and provide a nutritious protein boost for waterfowl.

The swamp on the edge of Lake Rotokare, 50km south of New Plymouth, reaches right up to a dense forest. The community-led project is headed by a charitable trust which cares for a 230ha reserve, protected by a predator-proof fence. It features in DOC’s publication, Magical places – 40 wetlands to visit in New Zealand (available here).

Sedges and rushes are closely related. Sedges are perennials; rushes may be annual or perennial. Sedge stems are typically triangular, unlike rushes. But both have solid stems, compared to the hollow stems of grass. There are more than 2000 species of sedge; Carex is a common plant family in New Zealand wetlands.

Clumps of Carex secta. (Credit: Nathan Burkepile, NZ Landcare Trust)

How to plan a wetland restoration

Wetland expert, Nathan Burkepile says thinking, researching, and planning need to come before you start digging anything. You don’t have to do everything at once. Nathan suggests designing and implementing your project in stages.

It’s important to ask yourself:

• what do you want to achieve?

• what is there now that could be included in your plan?

• what do you want to improve?

Nathan says the two most common motivations for landowners he works with are improved biodiversity and water quality. Chapter 2 of Landcare’s Wetland Restoration Guide has excellent advice.

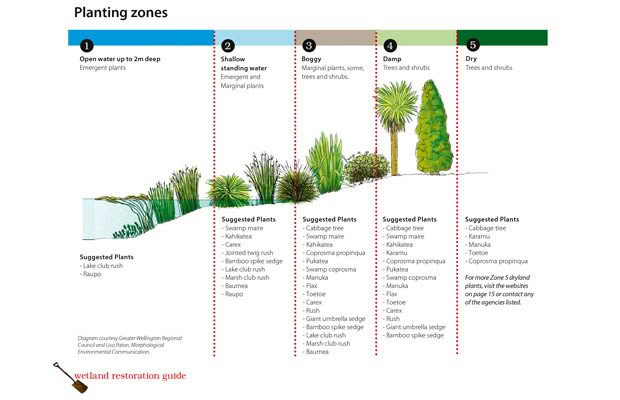

Credit: courtesy Greater Wellington Regional Council and Lisa Paton, Morphological Environmental Communication, www.morphological.co.nz

It recommends sketching a rough concept plan, showing a bird’s eye view diagram of the area to scale, as it exists now and the same view, as you’d like it to look once developed.

Google Earth can help as a basis for mapping. Ask your regional council if it has detailed contour information on your block as it helps when working out level changes and mapping zones. Zones are organised around different water levels and the plant types that thrive in them.

It’s important to find out how water gets into your wetland:

• has the water table surfaced?

• is it fed by groundwater or runoff, or both?

Think about your land’s place in the water catchment

The catchment influences the amount and regularity of water inflow and what it carries in the way of sediment, nutrients, and possible pollutants.

(Photo credit: Matt Paulsen)

A lifestyle block is unlikely to contain an entire catchment. It will be affected by high nutrient or sediment run-off from larger or more intensely-farmed properties on the land above you.

Ideally, get neighbours to work with you for the benefit of the whole catchment. Catchment groups are strongly encouraged by the NZ Landcare Trust, councils, and industry bodies. Seed funding may be available.

Cleaning up the water

If sediment-heavy water flows into your wetland, the key to cleaning it up is to slow it down. The slower it goes, the more sediment drops out. The best strategy is a sediment trap above a dam or wetland system, says Nathan. Without a sediment trap, the wetland will quickly fill with silt.

You’ll need to dig a trap out periodically; the silt will be rich in phosphorus and may be a useful soil amendment on other areas of your block. There are also native and exotic species that do a great job of sucking up nitrogen from nutrient-heavy run-off.

Consult local plant advisers about what works best in your area. It’s possible hemp may be a good option for this purpose in the future, but growing it is still heavily regulated.

How to bring in the birds and other wildlife

Waterfowl such as bittern, rails, spoonbills, and Muscovy ducks prefer shallow water, less than half a metre deep. If you’re excavating soil to increase water retention, create wave-shaped edges and gentle slopes, so it’s easy to walk down into the water.

Give your digging contractor specific instructions or most will create a typical farm dam which has steep sides and straight edges.

The margins around the water are essential waterfowl habitat. To create good habitat:

1. Plant densely at the water’s edge to provide nesting areas.

2. Don’t tidy up dead wood as it provides insect habitat and organic matter. More insects mean more food for birds and greater biodiversity.

3. Create roosts by jamming large rocks or dead logs upright in the water – it’s best to get that done when you have the digger on site.

4. Rats and mustelids are strong swimmers, so artificial islands and snags won’t be predator-proof – talk to your council, DOC or nearby landowners to get advice about what pests are in your area and what methods work best to control them. Effective pest control takes multiple, long-term approaches.

RACHEL’S TIPS

Consider volunteering at one of the many restoration projects around the country. It’s an excellent way to learn more about wetlands and contribute to your local environment.

Many natives are easy to germinate. If you can plan two to three years out, you can grow a lot of your plant stock yourself. Author Rachel Rose has a forest nursery.

The plants include karo, a useful pioneer species, which will shelter the drier margins of a regenerating wetland on her and her partner’s block. These resources from DoC are very helpful if you want to propagate natives: when to collect seeds and how to propagate them.

4 FREE WETLAND RESOURCES

1. Wetland Restoration: A Handbook for New Zealand Freshwater Systems

This book is a large, richly-illustrated guide, published in 2010. Its second chapter has a great template for planning a wetland restoration. It contains a host of links to additional information, and you’ll find lots more on the Landcare Research/Manaaki Whenua website too.

This is an independent, charitable trust that supports landowners, farmers, and community groups to carry out sustainable land and catchment management projects (not to be confused with Landcare Research/Manaaki Whenua, which is a government-owned institute).

It supports the establishment of catchment groups. If you’re in an area covered by one of its eight regional coordinators, you’ll find them a wealth of practical advice and assistance.

The National Wetland Trust (NWT) is a non-profit organisation established in 1999 to increase the appreciation of wetlands and their value to our environment. The website has many practical resources.

DoC’s wetland information includes a guide to plants, wetlands region by region, and the best wetlands to visit around NZ.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.