Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden: A couple’s one-hectare paddock is now bursting with art and native plants

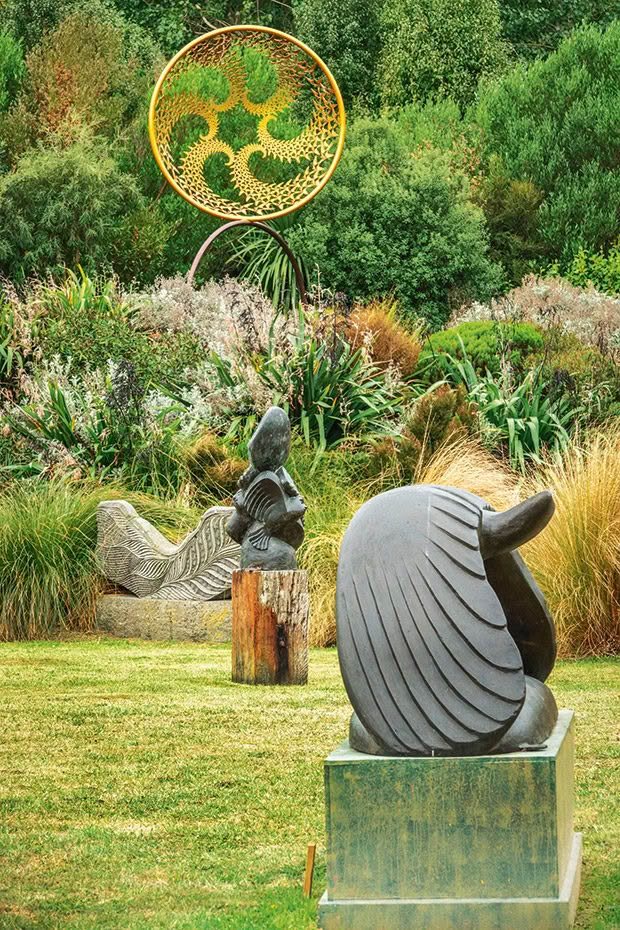

Neil Dawson’s Vortex is perched on the highest point in the garden, overlooking (back to front) Canoe by Christchurch artist Doug Neil and two works (Giotto’s Angels and Flight) by Llew Summers.

One couple, one hectare, and a thousand more years in which to write a vision upon the land.

Words: Cari Johnson Photos: Brian High

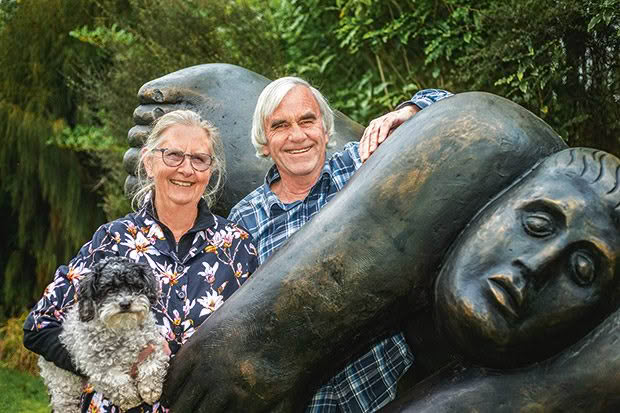

Peter Joyce looks very much the gardener as he weaves in and out of the natural rooms and hidden corridors that make up his one-hectare front yard. There’s a twinkle in his eye and his garden sculptures are like children, beaming back at him and peeking from behind tōtara and rimu walls.

Few would have expected Peter, a respected dean and professor of psychiatry, of having two green thumbs. His wife Annabel Menzies-Joyce, a landscape architect-turned-sculptor, was always the one knee-deep in native bush.

“I dragged Peter to the West Coast so I could run around in the bush, while he’d sit back in the car reading psychiatry books. These days, he’s read just about every book about native plants,” says Annabel.

Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden, 18-kilometres southwest of Christchurch, is as much a commitment to biodiversity as it is multi-dimensional art. More than 8000 native plants and trees flourish on the once-bare block of land below Annabel and Peter’s house. For Peter, the tōtara, mataī, and kahikatea trees are about regenerating the landscape for generations to come.

“I’m planting for a thousand years. Native plants make a statement about New Zealand’s identity. We’re not English — our identity isn’t oak and willow trees. Our flora and fauna are unique to the rest of the world,” he says.

In the early days, this flat patch of land was little more than a dusty paddock grazed by the couple’s daughter’s horses. Both born and bred in Canterbury, in 1989 they moved from Christchurch to the 2.1-hectare section with their three daughters. Annabel, who grew up on the Banks Peninsula, craved a landscape reminiscent of her rural upbringing and remained a country girl at heart. When their children left home, so did the ponies.

Off Balance by Arrowtown artist Fiona Garlick.

So what are a psychiatrist and artist to do with an empty paddock? Peter, the then-dean of the University of Otago in Christchurch, was hardly a gardener when he raised his hand to build tracks and wrestle weeds at a nearby community reserve.

“I initially thought of gardening as a cheap way to get exercise instead of paying for a gym membership,” he says. It was only a matter of time before he planted a few native trees along the couple’s fence line.

Chuffed as any gardener would be with their handiwork, he started eying up the rest of the property. “I went to Annabel and said, ‘Well that was easy, I think I’ll plant the whole paddock.’”

Llew Summers’ The Spirit of the Journey series leads through a corridor of lowland ribbonwood to Follow Me, one of the largest sculptures in the garden. The 10-tonne bronze sculpture sat in a public park in Christchurch for nearly a decade until Peter and Annabel bought it.

Annabel, a trained landscape architect, has long had an eye for landscapes and detail. Before turning to cast-glass sculpture, her colourful oil paintings described the tumbling hills of bush that she so loved to visit on weekends. She imagined their paddock, its towering podocarps tickled by dense underbrush. Except in this landscape, Peter would use plants instead of paint.

“Annabel knew more about native plants than me. She knew that a thousand years ago, before humans, this land would have been a forest dominated by tōtara, mataī, kahikatea. So that became the essence of our core planting.”

Not long after, Peter announced another grand idea. “Rather than planting trees for the sake of planting trees, I thought the garden should have a purpose. Since Annabel was an artist, I suggested we create a sculpture garden. Of course, I didn’t have any idea how to make one,” he says.

Peter and Annabel like to give artists free rein when commissioning a new piece. Doug Neil created The Rocks, a five-piece series carved from Timaru bluestone, after Peter asked him to create a piece for the grassy patch near their pond.

Despite working full time, he rolled up his sleeves and, bit by bit, the land began to lose its dusty, horse-and-saddle look. “Annabel instructed me to plant in clusters to create rooms, spaces, corners — and absolutely no straight lines,” he says. As his knowledge of native vegetation grew, so too did the garden.

Peter took creative licence by planting rare and threatened species alongside the growing podocarp bush, with pockets of beech (black, red and silver), rimu and even a few kauris.

That’s not to say the transformation was a walk in the park. There were plenty of tough decisions along the way; decisions often debated over an afternoon wine with the couple’s circle of creative mates. The late Llew Summers, a friend and renowned Christchurch sculptor, initially suggested a sculpture garden would need to be “at least” 1000 hectares to be successful.

- Peter and Annabel rest in front of Ecce Homo, Behold the Man by Llew Summers.

- Passing Through by Alison Erickson.

- Sea of Life (front) and Strange Fruit (back) by Christchurch artist Tony O’Grady.

- Mother’s Best by Phil Newbury.

- Calyx by Hurunui artist Sam Mahon.

- None So Blind by Graham Bennett.

- In Flight 2 by Titirangi artist Rebecca Rose.

“Llew was always supportive but would give his opinion freely,” says Peter. “We spent a long time debating what to name the garden until one day he turned up with a sign with ‘Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden’ on it.”

It was over another glass of wine, this time celebrating Annabel and local sculptor Doug Neil’s joint exhibition at the Form Gallery in Christchurch, that the couple commissioned their first work. Peter asked Doug, who created small carvings at the time, to describe the sculpture of his wildest dreams.

“Great, we’ll take it,” Peter told him, pointing to a grassy bank between the two ponds. “There was a space for him to create a big rock sculpture — I don’t think he quite believed me. And that was our first commission.”

Finnie, a mini schnauzer, enjoys trotting around the garden with his owners, occasionally pausing to sniff out sculptures like (pictured here) Interdimensional by Christchurch artist Matt Williams.

These days, 20 permanent contemporary sculptures are tucked into the nooks, crannies and groves of the garden. There’s no goal or fixed rule for adding new pieces; just like the plants, the couple has developed the grounds gradually over the years — and the garden can accommodate even more sculptures. In March 2021, between 60 and 100 pieces will inhabit the woodland during Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden’s annual three-weekend exhibition.

While art curator Melissa Reimer leads the process, Peter helps her refine the landscape so each piece can shine. He’s more than happy to chop a branch here or move a tree there but draws the line at filling the man-made ponds with anything but rainwater. One year he told Melissa to do the rain dance when she suggested he use a hose — luckily, it rained.

This is a man who is unafraid of shooing his wife away from the garden. Once or twice he has “fired” her after an accidental chop of a native plant with the weed-eater.

Many pieces reflect the couple’s regenerative vision or comment on native species that have been lost through colonialism — such as Alison Erickson’s Bureaucracy and the Huia. “You can interpret that in any way you like, but many of us wonder about what bureaucrats are doing to prevent more species from going extinct,” says Peter. Adds Annabel: “Huia became extinct because everyone wanted their feathers.”

“I’ve planted 99 per cent of everything in the garden so no one really is allowed to do anything to it. Perhaps one day I’ll have to accept the need for another gardener, and I’ll oversee them,” says Peter. “Hopefully, it will all be established by then.”

The native woodland, still in its infancy after a decade of hard graft, nourishes the land and its locals. Even the smallest residents have taken notice. Native birds such as pīwakawaka (fantails), korimako (bellbirds), kererū and riroriro (grey warblers) have replaced the once-ubiquitous skylarks and plovers that flocked to the open paddock.

“We don’t have tūīs yet, but they’ve been released on the Banks Peninsula,” says Annabel. “We’re hoping they breed and come our way.”

Visitors often comment that the man-made creations enhance the natural habitat. That’s no accident, says Annabel. Many of her cast-glass sculptures are shaped around roadkill skeletons or skulls found on adventures into the bush. She exhibits them in the garden, Form Gallery, and Quadrant Gallery in Dunedin.

Asteroid-Ullysina and Asteroid-Juno by Doug Neil.

“We prefer sculpture that ties into the environment, either by resembling it or making a statement about it. Those types of pieces pair well with plantings. Native plants are a much better backdrop for sculpture than pretty flowers.”

Early mornings and hard yakka come as second nature for Peter, who spent nearly 40 years running clinical trials and writing papers on depression, bipolar disorder and eating disorders. Since retiring in 2016, his green thumbs now extend well beyond the garden.

(Front to back) Flight by Llew Summers, Ngaio by Christchurch artist Andrew Drummond and Locate by Graham Bennett.

When he’s not helping further develop the community’s native bush, he co-chairs the Te Ara Kākāriki charity trust, a long-term project to plant a native greenway from the sea to the alps across the Canterbury Plains. Once a week, he volunteers at Hinewai Reserve, an ongoing 1100-hectare ecological restoration project on the Banks Peninsula that’s transforming gorse-riddled land into native bush.

“Peter used to stay up until 2am writing papers, and now, he’s still up late, only reading books on sculpture, art and gardening,” says Annabel. “It’s an absolute obsession.”

Annabel holds Momo, a bichon-poodle cross, in front of Llew Summers’ Follow Me.

The couple is more than happy to enjoy their garden of purpose when the sun dips behind the hills, and visitors are long gone. And on particularly fine evenings, Peter can be found sipping a glass of wine in the rimu grove, drinking in the ambience and imagining the forest that once was.

NO STRAIGHT LINES

Natural curves throughout the sculpture garden keep visitors ambling around ponds and paths, which almost always lead to a piece of art. When planning the garden, the couple avoided straight rows of plants, instead choosing to create rooms for the artworks.

“I taught Peter to plant spaces with associations of plants. In our garden, you’ll find areas that are predominantly beech, rimu, or kahikatea, which are planted to the prevailing conditions.”

Red and yellow tussocks wave gently around the zig-zag bridge built from (rather heavy) macrocarpa planks. “Annabel was standing up on a trailer telling me to move the panels here and there — because it has to look good on Google Earth,” says Peter. “And you can actually see it on Google Earth.”

Foliage, composition and movement were also taken into consideration. Cabbage trees add texture, long strands of tussocks draw the eye upwards and red tussocks wave beautifully in the wind. Trees are contrasted with woody shrubs, flaxes or, whatever Peter thinks will look nice.

It’s a style of gardening for which Peter, who’s far from a perfectionist, is well-suited. “Rough enough is good enough for me,” he says. “It’s still random, but that’s nature.”

AN ANNUAL AFFAIR

Right from its conception, Peter and Annabel hoped their paddock would serve emerging and established artists. The couple first transformed the garden into a public exhibition in 2014, a tradition that has continued every autumn for seven years.

These days, between 60 and 100 contemporary sculptures are exhibited at Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden over the first three weekends in March. The event features more than 25 artists from throughout New Zealand, including a mix of emerging artists and notable Canterbury sculptors such as Graham Bennett, Bing Dawe, Neil Dawson and Alison Erickson.

The bronze river birds seem to be in their natural habitat as they dance among the cabbage trees that frame Bing Dawe’s gateway sculpture.

It’s an event the couple couldn’t do alone. Curator Melissa Reimer has organized the outdoor event since its inception, a year-round job that often requires Peter to dig, prune and rearrange as the pieces are installed.

“Visitors will either come for the plants or sculpture,” says Annabel. “We want to educate people, so those who come for the plants are subtly educated about sculpture — and vice-versa.”

ANNABEL’S SCULPTURES

The bones, skulls and roadkill remnants scattered about Annabel’s studio are just the beginning of her artistic process. She uses glass casting, a multi-step process that ends in a kiln, to create delicate replicas of animal remains.

“Bones are amazing things. They are like little sculptures in their own right.”

For her All That Remains series, Annabel made impressions of fish skeletons to comment on New Zealand’s declining fish stocks. Using natural materials allows her to voice her concerns about climate change and biodiversity loss.

Annabel’s work can be seen at Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden, Form Gallery in Christchurch and Quadrant Gallery in Dunedin.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.