Why growing a food forest can be trickier than you think

Imitating nature to grow food seems like a good idea but creating a thriving food forest can be tricky.

Words & images: Sheryn Dean Additional images: Tessa Chrisp

Who: Robyn & Robert Guyton

Where: Riverton, 40km west of Invercargill

What: 0.8ha (2 acres) food forest supplying 60-70% of their (vegetarian) diet

Web: www.facebook.com/TheForestGardeners, www.sces.org.nz

Food forests have become extremely popular in western gardens since the 1980s. A food forest is a mix of edible plants grown in a forest-like environment. The idea is they’re self-sustaining with low inputs and minimal maintenance.

I studied the seven layers. I selected trees, plants, and seeds best suited to an organic system, and dedicated a north-facing slope to this wondrous idea. Several years later, I started asking others how their food forests were working out. I wasn’t the only one disillusioned and disappointed.

The problem is that when I imagined a forest, it looked like New Zealand native bush, a dense entwinement of canopy trees, vines, and shrubs. But most of the foods I like to eat don’t grow in that environment. Peaches, oranges, lettuce, tomatoes, potatoes, and courgettes all need lots of sunshine, fresh air, plenty of nutrients, and their own root space to perform well.

I’ve seen successful sub-tropical food forests north of Auckland. They incorporate the plants that prefer a jungle-like environment, such as bananas. They love the moist, humid conditions that would rot a peach crop. It’s very different for anyone in a colder climate. In this two-part series, I’ll share what I learned creating a food forest in the south Waikato.

3 TIPS FROM NZ’S TOP FOOD FORESTERS

Robert and Robyn Guyton are the custodians and creators of this green Riverton revelry. Their property is home to the South Island’s most established food forest, with over 480 productive trees, shrubs, and other plants mingling in symbiotic bliss with natives, birds, and insects.

It includes 90+ heritage apple varieties, more than 30 other fruit and nut trees, berries, eight sorts of rhubarb, and 50 different herbs.

Tip 1: Follow nature’s lead

The first step is to stop using chemicals. “Let the edges grow wild and put vegetables in your flower garden,” says Robyn. “Learn to love the plants that grow voluntarily and find out what they’re good for. “Add some layers of every height and depth and replace ornamental exotics with edible or native plants. Lawns, straight lines, and unproductive gardens are so last century.”

Tip 2: Let your soil keep its clothes on

If you dig weeds out of your lawn or poison them, they’ll keep growing back because the soil might need something. “Dock, for example, brings iron,” says Robyn.

The Guytons’ food forest borders NZ’s southernmost coastline. Their forest canopy includes a lot of natives that thrive in the cold, sometimes very windy conditions.

“If you let it rot down on site, it’ll give the soil all the iron it needs. Nature doesn’t want bare soil because the sun beats down on it and takes away some of its nutrients, and rain washes them away. Nature just wants (the soil) to be covered.”

Tip 3: Go at it wholeheartedly

Robert says even after 25 years, he’s still adding plants, and somehow, there’s always a place for them. “Rather than having to clear a big area and have it as fruit trees and grass, we discovered you could do everything in there,” says Robert. “You could grow all your herbs, berries, and vines, plus have your native canopy still in place.

“We thought that was perfect, and it is.”

THE FOUNDATIONS OF A FOOD FOOD FOREST

The most important factor when selecting trees for your food forest is to choose the right varieties for your environment. Trees that like their growing conditions will be low maintenance compared to those that don’t.

All plants have specific soils and climates they prefer. Different varieties of the same plant may like disparate conditions; there are apricot varieties that flourish in Auckland, and avocadoes that fruit in the South Island.

Sheryn’s tip: talk to local gardeners and nursery people to find the varieties best suited to your block.

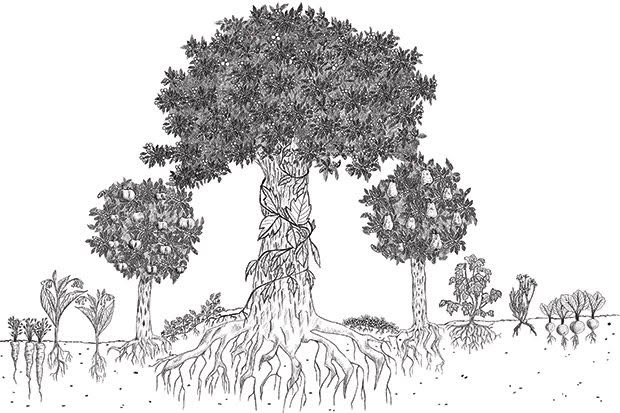

The seven layers of a food forest

1. The canopy trees (eg, large fruit & nut trees)

2. The low tree layer (eg, dwarf/low-growing fruit trees, bamboo)

3. The shrub layer (eg, currants, berries, flax)

4. Herbaceous perennials (eg, comfrey, mint, sage, tansy)

5. The roots (eg, carrots, beets, potatoes)

6. The soil surface (eg, ginger, strawberries)

7. The vertical layer (eg, kiwifruit, grapes)

The canopy

The bones of any landscape are the largest trees. In a food forest, canopy trees – if you have them – should produce food or provide shelter. Chestnuts and English walnuts are good options. The crop drops to the ground (no need to worry about climbing them), and you get a wide canopy. The drawback is you end up fossicking amongst other plants to gather the nuts.

These canopy plane trees were pruned up as high as the cherry picker could go to let in maximum sunlight. The real problem turned out to be their established and extensive root system. Most sub-tropical plants planted under canopy trees tend to be extremely nutrient-hungry, requiring lots of food and mulch. Those under my plane trees barely grew until I started feeding them – literally, by the truckload – and still aren’t producing.

Another problem is how much the established root systems of big trees will dominate and consume available nutrients. I put delicate tropical plants under some existing plane trees for protection from winter frosts. Unfortunately, I underestimated how much the plane tree’s roots would suck the nutrients from the soil. To remove the plane trees, without destroying the precious avocados and bananas growing under them, will cost a fortune.

Sheryn’s tip: choose canopy trees very carefully. Wide canopies produce a large amount of shade, and those with shallow, wide root systems will take away nutrients from plants below.

Shelter trees

Shelter trees are essential if you’re planting on a windy site, but too much shelter can be detrimental. Trees planted solely for windbreaks often became a nuisance in time when they:

• create too much shade;

• steal nutrients from production trees/plants;

• create still, humid conditions that allow pests and diseases to thrive.

My block isn’t a high-wind zone, so I planted feijoas on the north-west corner and large Japanese plums on the windward western side. They produce a lot of fruit, even in bad years, and the ones I can’t reach are good bird feed. Macadamias and hazels make good shelter trees too. Bamboo is a quick-to-establish wind shelter. The edible Moso bamboo is a spreading type, but not overly invasive and can be kept under control if you cut off the big shoots that appear each year. You can eat them too.

This unpruned plum tree (Dan’s Early Jewel) shelters the orchard from westerly winds, and provides ample tasty plums in the New Year.

Another good option is a mixed hedgerow containing the more fringe food trees, such as elder, hawthorn, maqui berry, rosehips, tagasaste, tangshi, and fuschias. They’re interesting, don’t grow too tall or wide, and are productive, even if it’s just as food for the birds. Tall, quick-growing alders are often dually utilised as a windbreak and to fix nitrogen in the soil.

Tagasaste growing as shelter and to fix nitrogen around avocadoes.

Sheryn’s tip: The trees around the edges of your food forest get the advantage of space and sunlight. I should have put my stone-fruit around the outer perimeter where breezes would inhibit leaf curl and brown rot.

Nitrogen fixers

Some food foresters contend that at least 25% of trees should be nitrogen-fixers. These host nitrifying bacteria and produce excess which helps to feed the surrounding plants. All plants host some nitrifying bacteria, but some create a lot more than others.

The nitrifying bacteria hosted in the nodules on these clover roots capture nitrogen from the air and turn it into nitrates that plants can assimilate.

Sheryn’s tip: Common nitrogen-fixing plants include: Canopy – alders, locusts, wattle; Sub-canopy – tagasaste (tree lucerne), carob, liquorice; Herbal/climbers – anything in the legume family, eg peas, beans; Ground cover – clover

2 IMPORTANT PLANTS IN THE GUYTON FOOD FOREST

1. Cabbage trees

Robert Guyton is a big lover of native trees, especially cabbage trees. He used them as the framework for their forest canopy, for several reasons: they’re very hardy, the leaves are good fire starters, and they feed and provide habitat for birds, particularly starlings (which love to eat pests such as caterpillars).

2. Cow parsley

Weed control might seem difficult in a food forest, but the Guyton’s don’t have any weeds to control. They use a range of plants, including cardoons, fennel, and comfrey to help prevent weeds from taking hold. But their best performer is cow parsley (also known as wild chervil, Anthriscus sylvestris). It hosts ‘good’ hoverflies, which feed on pest insects, and it covers the soil, preventing weed seeds from germinating.

To many people, the Guyton’s food forest looks chaotic. However, Robert says it’s a far more complex, sophisticated order than a ‘conventional’ garden.

It’s also easy to control, says Robert. He simply walks over it, bending the stems at ground level. It doesn’t kill it, but it takes a while to rejuvenate, letting in more light for small trees, vines, and berries growing in it. The BHU (Biological Husbandry Unit) at Lincoln University found that large swathes of cow parsley grown under apple trees greatly reduced the incidence of black spot, as its spores couldn’t spread.

HOW TO PICK THE BEST FRUIT TREES

The rootstock of grafted fruit trees determines how tall they grow. In general, the bigger/taller the tree grows, the more robust it is. Dwarf trees have small root zones that can’t access moisture and nutrients to the same extent as a large tree.

Fruit trees grown from seeds are generally the largest and most robust of all trees. However, apples are commonly grafted onto different rootstocks with known properties, eg dwarf.

If you want an easy-care tree to survive a low-maintenance food forest environment, choose a hardy, large-growing rootstock that suits your soil. Let it grow and invest in a ladder.

MORE HERE

10 unusual edible perennials grown at a permaculture farm near Hastings

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.