Slower walking, ageing fast: Why gait speed may be an ageing indicator

Scientists believe that how fast people walk in their 40s is a sign of how their brains, as well as their bodies, are ageing.

Words: Rosemarie White

Dunedin, one of the southern-most cities in the world, has the distinction of having one of the most closely examined populations on the planet. Yellow-eyed penguins, royal albatross, sea lions perhaps?

No, it’s the 1037 humans born in Queen Mary Maternity Centre at Dunedin Hospital from April 1972 to March 1973, part of one of the most comprehensive investigations into human development. The Dunedin Multi-Disciplinary Health and Development Study is as important to the world’s knowledge of how humans age as the Framingham Heart Study is for cardiovascular disease and the Nurses’ Health Study is for women’s health.

THE VALUE OF LONGITUDINAL STUDIES

Dunedin is not the biggest or the most extended investigation but its high retention rate — about 95 per cent of the original cohort has stayed with the study since it launched — ensures its importance.

Every few years, team members conduct intensive cognitive, psychological and health assessments. They interview every member of the research cohort as well as their teachers, families and friends, and review financial and legal records, promising them complete confidentiality in return for the details of their lives.

This long and patient tracking also identified a troubled subset of the Dunedin cohort. At three years old, some participants were identified as having poor brain health; by 15, about a third of the study’s boys took part in some degree of delinquency while a subset offended more frequently.

The habitual offenders had been making trouble from age three and had arrest records starting before their teen years. Papers showed these boys did poorly in neuropsychological tests, verbal skills and verbal memory. They measured highly for impulsivity, and were likely to engage in substance abuse as they grew older.

In 2002, at age 26, this same group was involved in criminal activity, a pattern that persisted well into their 30s.

NURTURE AND NATURE

If the Dunedin study is considered a representation of the wider population, it shows that 20 per cent of people account for the bulk of social costs: crime, welfare payments, hospitalizations, cigarette purchases, fatherless child-rearing, and other indicators of social dysfunction.

This problem group could be identified from the beginning: they scored low on early language skills, fine and gross motor skills, neurological health, and self-control. Often, they grew up in poverty and suffered maltreatment, disadvantages that have haunted them.

They even seemed to age faster than those who had a better start, with signs of ageing starting in their 30s, leading researchers to conclude the effects of stress can hit early. Childhood abuse and stress seems to erode telomeres — the caps at the end of chromosomes, associated with cell preservation — which may accelerate ageing.

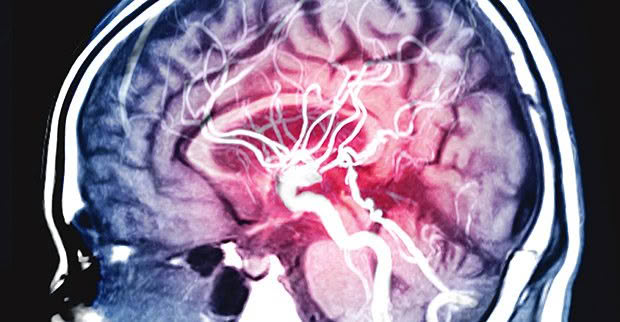

The most recent round of testing finished in April 2019, and the participants were again examined on several measures of everyday physical function. They were also assessed for signs of accelerated ageing — 19 different biomarkers ranging from blood pressure to dental health — and had neuroimaging tests to look at age-related features of the brain.

Their gait speed was also examined. Doctors often measure gait speed to gauge overall health, particularly in the over-65s, because it is a good indicator of muscle strength, lung function, balance, spine strength and eyesight. Slower walking speeds in old age have also been linked to a higher risk of dementia and decline.

GAIT-SPEED INDICATORS

Gait speed in the 45-year-old participants was recorded, focusing on the slowest 20 per cent and fastest 20 per cent, in three walking conditions: at their usual gait, at their normal pace while reciting alternate letters of the alphabet out loud, and at their maximum gait speed.

(If walking at speed while reciting every alternate letter of the alphabet doesn’t sound challenging, please try it.)

The slowest walkers averaged 1.21 metres per second, or roughly 4.34 kilometres per hour, throughout all three of the conditions, while the fastest walkers averaged 1.75m/s, or 6.276km/h.

The results were clear, a slower walking speed in your mid-40s is associated with poor physical function, poor cognitive health, accelerated biological ageing and compromised brain integrity. It is an indicator of looming problems decades before old age.

There was even a 16-point IQ difference between the fastest and the slowest walkers.

In a separate visual analysis of participants’ facial ages conducted by a panel, the slower walkers were also judged to appear significantly older than faster walkers and scored worse on tests that measured balance and grip strength.

The most remarkable aspect of the research is that testing cognitive functions in toddlers could predict how slowly those children will be walking at midlife.

“We should not assume that poor results of cognitive testing in three-year-old children in any way doom them to lifelong problems,” says geriatric medicine researcher Stephanie Studenski from the University of Pittsburgh. (Studenski wasn’t involved in the study but is the author of a commentary on the research.)

“But, rather, look broadly at what might be contributing to poorer performance and explore strategies to ameliorate these contributors. The human brain is dynamic; it is constantly reorganizing itself according to exposures and experience. Perhaps in this sense, brain health, reflected in brain structure, cognition, and gait speed, is not necessarily a first cause, but rather may be a consequence or mediator of life-long opportunities and insults.”

IMPACTS OF THE STUDY

If humans learn to understand the nature of the links this study seems to show, they might positively influence social factors that could boost biological longevity and neurocognitive function, and potentially help arrest cognitive decline.

It’s thanks to Dr Phil Silva OBE, founder and emeritus director, and the foresight shown by many people in Dunedin in 1972, that we know this much about our species.

The Dunedin Multi-Disciplinary Health and Development Study has produced more than 1200 papers on questions from the risk factors for antisocial behaviour and the biological outcomes of stress to the long-term effects of cannabis use.

One early finding, on the transient nature of most juvenile criminal offending, was quoted in the United States Supreme Court’s 2005 decision to prohibit the execution of underage murderers, citing research on the genetic make-up of certain individuals that can make them vulnerable to specific stresses.

And in 2017, the Dunedin team published a study that drew on decades of data to show that, contrary to conventional belief, the vast majority of people experience mental health problems throughout their lifetime.

MORE HERE:

What is epigenetics? What you need to know before getting a gene test

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.