At home with Tāme Iti: Explore the vegetable gardens, sunflowers and art studio of a Tūhoe activist

Tāme Iti has always used creativity to frame his social and political rhetoric. Now in his 60s, paint propels his inimitable style of agitation.

Words: Ann Warnock Photos: Birgit Krippner

The Tūhoe man with the moko; media figure, activist, pragmatist, global indigenous-rights warrior, performer, artist, grandfather, father and lover.

On a sunlit morning at Rūātoki, a small settlement inland from Whakatāne on the edge of thickly forested Tūhoe traditional land, New Zealand’s most-famed Māori campaigner, Tāme Iti, is at home mowing his lawns.

He is shirtless and clad in work boots, track pants and a bowler hat. A sheen of lawn-mowing sweat amplifies the impact of his tā moko before he apologizes for his bare chest, ducks inside and puts on a shirt.

Sunflowers and kai are grown in an experimental vegetable garden where ancient varieties and organic management dominate.

Tāme’s full facial tattoo, applied when he was in his early 40s at Rūātoki, was no theatrical stunt. “Like the language of te reo, moko is an intricate part of our past. I wanted to bring it into reality, to normalize it, to demonstrate it’s not a dying art. My moko is far bigger than me, and I’m just a cog in a wheel,” he says.

A cog maybe, but a high-profile one bearing perhaps the nation’s best-known moko, the resonance of which has been global. “A few years back a mate and I were jogging along the Thames in London when someone called out ‘Hey Tāme’. We were a bit stunned.”

At his 2015 TED talk in Auckland, Tāme appeared in a calf-length woollen tunic – tailored in Ōpōtiki from an old military blanket – teamed with a white dress shirt and cherry red bowtie. He often wears a top hat.

Tāme trains a hue (gourd) vine on a teepee. Māori traditionally used hue to store meat and carry water. “We eat them and also dry them and use them creatively.”

“The top hat is a teaser. It’s a symbol of colonization, and I’ve reclaimed it. Designing my clothes has been something I’ve always done, and I’ve used a tailor since the 1960s. Partly because I have very short legs, so nothing fits,” he says.

“My grandfather Pēku Purewa, who brought me up, dressed immaculately. And the woven korowai worn by my ancestors showed their mana. As a boy, my grandfather took me shopping in Whakatāne each summer as payment for helping on the farm. I was given the opportunity to choose my shoes or shirts or hat. It was magic.”

Tāme’s presence – with a top knot, top hat, mohawk, cap or beret – has punctuated the pressure points in Aotearoa’s political terrain from the 1970s. His propensity to question authority rather than acquiesce revealed itself at the age of eight when the headmaster at his local Rūātoki school announced that the speaking of Māori was forbidden on the school grounds.

White corn is used to make tortillas, which are baked in clay ovens, and there are five types of heritage kūmara, kamo kamo, taro and potatoes. “We don’t want to buy seedlings in town. Instead, we’re sourcing and sharing ancient seeds — one of our apple trees was planted by Ngāti Maniapoto in about 1860.”

Tāme, who had grown up speaking te reo only but had heard English on the radio and in town, opted to carry on. “I ended up writing thousands of lines on the blackboard after school: ‘I must not speak Māori.’”

He moved from Rūātoki to Christchurch at 17 to embark on an interior-decorating apprenticeship as part of a Māori trade-training scheme designed to urbanize young rural Māori. By then, his growing sense of the world as an inequitable space led him to connect with a nucleus of people engaged in resistance and protest.

The Vietnam War, the 1975 land march to parliament led by Ngāpuhi leader Dame Whina Cooper, the Bastion Point occupation, the Springbok Tour, anti-nuclear protests and Ngāi Tūhoe’s crusade with the Crown in the lead-up to its momentous settlement in 2013 are all part of his story.

Now 67, Tāme is no longer positioning himself in the frontline but is instead using his artistic practice as a platform for his political deliberations. “Art is an opportunity for kōrero. It’s a waka for social change. I feel a responsibility to provoke and sustain an ongoing conversation about Tūhoe’s history, our history and the narrative of tangata whenua and patriotism. Art has a different energy as a formula – it’s a good platform for demonstrating your thinking.

Tāme and his son, Toi Kairākau, who lives close by, with the maunga of Taiarahia behind. Tāme’s great-grandfather once farmed the land where Tāme and his whānau live. Tāme says he’ll continue to advocate for Tūhoe but “a younger generation must build the future. I’m now the kaumātua generation.”

“People want art that touches their heart and soul. I use art to talk about global issues – climate change, the commercialization of natural resources through capitalism and the displacement of indigenous people,” he says.

Poetry, art, oration and music have always occupied Tāme’s headspace. As a child, he carefully replicated comic strips. He started painting in his late teens, and, at 21, was enamoured by the poetry (and Marxist stance) of Hōne Tuwhare at the inaugural hui of the New Zealand Māori Artists and Writers Society at Te Kaha in 1973.

In the mid-1980s, during a lengthy stint working in addiction services for young Māori at the Tūhoe Kōkiri Centre in Rūātoki, he was deeply inspired by a workshop in the United States that examined the power of art to “heal the spirit”. During the 1990s he worked briefly as a radio DJ in Auckland – he loves the rhythm of house music (electronic dance music), classical music, reggae and the Kiwi sound of Fat Freddy’s Drop. Theatre has also been part of the mix.

In 2007, he played the lead part in theatre-maker Lemi Ponifasio’s production of The Tempest, which toured in Europe. Staged after the now-infamous anti-terror Urewera raids, the High Court relaxed his bail conditions for him to pursue the role.

In recent months, Tāme has become vegan, which is allowing him better management of his diabetes. He loves cooking — he worked in a restaurant in Hamilton in the 1970s — and says the switch to plant-based eating has been straightforward. “I feel amazing.”

“I now paint full-time. I don’t have a special studio. I just paint somewhere in the house. I’m not represented by a gallery. I don’t want that. We hire a space when we need it,” he says.

While the pursuit of art is part of Tāme’s weekly timetable there are other calls on his time. A Tūhoe-owned nationwide honey enterprise involving negotiations with landowners across the country is part of his portfolio.

He and Sir Wira Gardiner are currently in talks with the Australian honey industry over the issue of copyright surrounding the use of the word mānuka. Discussions about the production of hemp and medicinal cannabis are in the frame, and he’s part of a Tūhoe sustainable housing project. “Honey is a sustainable way to utilize land – an alternative to traditional farming. No chemicals and fences required.”

Sustainability is centre stage at Tāme’s home base on a tract of ancestral land above the Ōhinemataroa River. He grew up on the site; it’s his whakapapa, his place and his identity.

He shares his home with his long-term partner Maria Steen, a former social services practitioner, and Maria’s two daughters, Amie and Tia, their partners and three mokopuna. Living simply, communally and self-sufficiently is the theme. “With six adults and three children living here, we pull together. We each take responsibility for cooking a meal, and we share the jobs, the kai, the resources, the internet costs, the maintenance and the tools.

“I see our role as maintaining and building this place in a sustainable way so that it draws people together now and for the next 100 years. But this isn’t just an approach for Tūhoe; it’s a global approach to the way we live,” he says.

Three large clay ovens under a largescale arbour near the house enable the whānau to feed a crowd. Free-range chooks, pigs, vegetables and herbs are grown onsite. “We don’t want to be slaves to the supermarkets, and we’re moving away from processed food,” he says.

Coughs and colds are treated with “boiled kawa kawa leaves, mānuka honey and good kai – no sugary pills and no hamburgers and chips”.

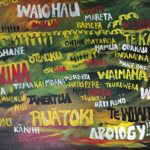

- Untitled, 2015 features the names of hapū and locations in the kingdom of Tūhoe

- Tāme cleaned graffiti from a wall behind a post box in Tāneatua and painted a mural. “Whatever is happening on a particular day, I’ll always allocate time to paint. It’s a discipline and focus, and I get in the zone”.

- The Crown’s return of Te Urewera to the people of Tūhoe (the former national park is now administered by the Te Urewera Board comprising joint Tūhoe and Crown membership) is the central theme in the painting Te Manawa o Tūhoe (2014).

Seven years ago, Tāme was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes – a condition he says has been straightforward to manage but has heightened his awareness “of food as a medicine”.

He has two sons with his former wife, Australian Ann Fletcher. The couple was married for six years in their early 20s. Wairere, 47, works in the music industry in Auckland and Whakatāne-based Toi, 44, is a journalist, former Māori Television presenter and was recently elected to the Bay of Plenty Regional Council.

There is conjecture that Tāme engineered both Toi and Wairere’s romantic partnerships. “Just like our ancestors did.” His third whāngai (adopted) son is Te Ika roa o Te Rangi (26).

In the kitchen at Tāme and Maria’s home, there are mugs of coffee, three people have visited, 18-month-old mokopuna Te Hirina is eating a sandwich, and Tāme’s mobile is buzzing. “It can get a little bit crowded around here,” he says.

Outside on the lawn, sitting on kitchen chairs alongside artichokes, silverbeet, parsley and borage, the dialogue is philosophical. Tāme believes in a world of spirituality beyond this life but harbours “little respect for how Christianity was used as a colonial vehicle to manipulate the hearts and minds of tangata whenua”.

Tāme and Maria’s much-loved bichon frise, Nehe, is blind. “We lost him about five years ago, and that’s when we realized he’d lost his sight. He’s our baby and sleeps on the bed.”

He is quick to acknowledge those who’ve inspired him; land rights activist Eva Rickard, James K Baxter “for his actions in supporting the homeless”, Ngāpuhi academic Taura Eruera, and Tūhoe leader Tāmati Kruger “for his visionary thinking for Te Urewera”.

While the social complexities of Aotearoa have shifted since Tāme pitched a “Māori embassy” tent at parliament grounds in 1972, his voice as an agitator and his art remain in demand. A week after the Christchurch mosque shootings, he was activist-in-residence at Massey University. He used his platform to promote kōrero on racism, bringing people together and solutions – his visit drew record crowds for an invited speaker on campus.

Despite his mahi across four decades, Tāme says it’s been important to have a private life. Away from the fray, the modest village of Rūātoki has been his place of peace. It’s his kāinga in the kingdom of Tūhoe, where his latest artwork is propped up against a sofa in the living room. “I always come back to Rūātoki – I have never left.”

ART IN MOTION

Tāme at work in his studio.

Tāme’s recent artistic collaborations include Billy Apple, Owen Dippie, filmmaker and visual artist Tracey Tāwhiao, and photographer Birgit Krippner. His works are predominantly oils on stretched canvas, acrylics on paper, with a reduced palette. His art often features the movement of large groups of people and silhouettes within a built or figurative landscape. “Painting has always been in my blood.”

Tāme has exhibited at select galleries in Auckland, Christchurch and Ōtaki in the past three years. Pop-up spaces are used for his collaborative shows. In 1998, Tāme and Auckland arts philanthropist Dame Jenny Gibbs negotiated the return of Colin McCahon’s Urewera Mural (1975), stolen from the DOC HQ at Lake Waikaremoana the year before. The painting now hangs in the tribal chamber at Tūhoe’s energy-generating headquarters in Tāneatua.

A SNAPSHOT OF TŪHOE

● Some 600 people live in and around Rūātoki. The population is closely affiliated with Ngāi Tūhoe.

● Tūhoe didn’t sign the Treaty of Waitangi, but the Crown assumed control over its land. The iwi suffered invasions, indiscriminate raupatu (confiscation), wrongful killings and scorched-earth warfare.

● In 2013, following a tragic history of interaction, Tūhoe and the government reached a settlement that included financial redress of $170 million and an apology from the Crown.

● Ngāi Tūhoe has a population of about 40,000; 83 per cent live outside Te Urewera, many displaced by the past. Of the 4000 remaining within Te Urewera, a large proportion has suffered severe socio-economic deprivation.

● In 2007, the police staged what’s become known as “the Urewera raids”, believing militia groups were mobilizing in the bush. Seventeen people were arrested under the auspices of the Terrorism Suppression Act. None were charged.

● In 2012, in the aftermath of the raids, four people — including Tāme Iti — were found guilty of illegal possession of firearms. He served nine months in prison. “It was crazy, but I’ve just had to let it go.”

● The Independent Police Conduct Authority later found aspects of the raid were unlawful. In 2014 commissioner Mike Bush stood on the front porch at Tāme’s home and apologized for the manner in which the raids were conducted.

OTHER STORIES YOU MIGHT LIKE

Why Ōtāhuhu artist Lissy Cole is hooked on colourful crochet (and owns the word fat)

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.