Take a tour of furniture designer Ed Cruikshank’s alpine home and studio in the Queenstown Basin

This couple, one a furniture designer and the other a general practitioner, work in vastly different disciplines, but are aiming for precisely the same goal.

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Rachael McKenna

Deep in a person’s DNA is the beginning of their story as an individual. What drives them, shapes the way they live, the possessions and habits they choose to bring into their lives and what, ultimately, makes them unique humans.

It’s curious, then, that a furniture designer and a GP, a couple operating in spheres so far apart, should come at their work with the same questions about what makes people tick.

“I like to know a person before I can design for them,” says Ed Cruikshank.

- Ed Cruikshank’s studio is across a pond from the main house. The pond connects the two buildings and anchors them visually to the site.

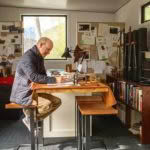

- Ed sits on his cantilevered bar stool surrounded by original sketches and maquettes of his design.

- The original prototype for his rocking chair (on the right), the Club Rocker, is part of the Iconic Collection.

Ed has created pieces for some of the world’s most particular collectors in his career as head of design, then sales, for the famous British brand Linley, owned by the second Earl of Snowdon, David Linley. In more recent years he has been busy with his Queenstown-based design practice, Cruikshank Furniture.

“This is where Ed and I come together,” says his wife, Tonya. “When we connect with our patients and customers, understand where they are coming from and what they feel, then we do our best work.”

Ed enjoys the human interaction aspect of design. “If people say they want me to design them a dining table, I might ask: ‘Want do you want a dining table for?’ Some of them raise their eyebrows and say: ‘Why do you think? To eat at, of course.’”

Coronet Peak is to the west, two valleys frame a peek of The Remarkables range to the east, and even Walter Peak is visible to the south.

To Ed, this is only half the story. A table can be eaten at, for sure, but it can also be where the homework is done, or the focus of long formal dinner parties and rowdy banter and debate. It can be where food is prepared and flowers trimmed to vase length, or it may stand as a celebrated work of art, bare and beautiful.

Whatever the reason, the most important thing is the human connection. He likes to understand his customer so he can create a piece that reflects their unique story.

Tonya wants to go beyond symptom-focused patient diagnosis. What people think is ailing them is only half the story for her. “I want to know how someone is living their life; how they are meeting their emotional challenges because life does involve joy and sadness.”

The house, only one room deep, offers alpine views from almost every window. The main living area features a Shane Woolridge sculpture (on the left, behind the sofa) called Missing Link and a bronze by Fiona Garlick. The heirloom oak tallboy dates to the 16th century and has been handed down through Tonya’s family. The cheeky pet lamb probably isn’t allowed to sit on the “Rufus chair” (in dark brown leather), named after a great-uncle who is Rufus’ namesake.

She sees the human psyche as a bit like sedimentary rock, showing its history in visible layers. In humans, experiences lay down future responses and reactions. And she wants to know what those strata reveal so she can adequately guide her patients into living their best life.

When Tonya sits in her grandfather’s chair by the fire at home in the magnificent mountains of the Queenstown Basin with Ed, son Felix (13) and twins Rufus and Neve (11), she finds moments of joy in just “being”.

(Incidentally, this classic “green-zone moment” is what she ultimately wishes for all her patients, so they get maximum amounts of healing oxytocin released into the bloodstream. But more on that later.)

The couple on an Ed Cruikshank sofa.

She was lucky to inherit the already-old club armchair with its colourful floral antimacassar from her grandfather, who inspired her career in medicine. It sat at home in her tiny flat in London’s Primrose Hill during her early years working as a junior doctor. Then she bought it with her to New Zealand when she and Ed settled here nearly 20 years ago. Ed’s “best-ever” gift is the chair’s restoration in hand-tooled leather.

Ed, watching Tonya, calm and smiling, in her much-admired grandfather’s chair, has an equally affirming moment (and loads of oxytocin, no doubt). His stellar career has spanned the heady days of 1990s London when the great and the glamorous whirled through the doors of Linley’s Kings Road shop. (On any given day, John Cleese, Elton John, David Bowie and Princess Margaret to name-drop but a few.)

The recognition made him confident of his design ability. This is fortunate, for when he initially sent the design drawings to a New Zealand manufacturer for a modern iteration of the club chair, the response was unexpected.

“Your measurements are wrong. The chair is too small.” He persisted, and the chair is now central to Ed’s renowned Iconic Collection. There is also a rocking version and one that swivels.

“Everybody likes a chair that moves. There’s something mesmerizing about being able to turn smoothly from one person or one view to another that has universal appeal.”

Tonya’s grandfather’s chair, once covered in floral fabric and a treasured possession since her days as a young doctor in London, is now restored in leather and is even more loved as the years pass.

And the small frame? Was it wrong? Not at all. “It sort of envelopes you, freeing the mindset. It is liberating.” Another oxytocin moment, maybe?

It was a fortuitous moment when a young Ed, just returned to his hometown of Stretton near Manchester after several gap years in France and Switzerland, spotted an ad for a cabinet-making course.

Most of his family are engineers and, from them, he had learned the value of making and fixing household items. But he hadn’t considered a career in cabinetry until he walked through the doors of Rycotewood College in Thame near Oxford.

Twins Rufus and Neve are not only musical and keen skiers but also passionate ice-skaters.

“I knew from day one that this is what I wanted to do. I couldn’t wait to get up in the morning to get to school. It was a ‘wow, this is me’ moment.” He followed that two-year course with a design degree from Ravensbourne University in London, a Bauhaus-inspired system of learning encompassing all the mechanical arts.

He wasn’t quite so purposeful in following up a friendship with a young medical student whom he met when they were both teaching skiing in Saas-Fee in Switzerland. Tonya and Ed had had 10 years of occasional dinners and a ski rendezvous engineered by a match-making friend of both, but there had been no wow/pow moments. (Being fair to Ed, he did have another romantic attachment at the time.)

Older brother Felix, leading the charge up the hill, is into ice hockey and the creative arts and is a bit of a drama star, says Tonya.

But a few months after the couple waved goodbye on the snowy slopes thinking they would be unlikely to see each other again. Ed ended his relationship. He contacted Tonya and events overtook them. Months of a long-distance email courtship ensued since Tonya was now in Australia. But after a few romantic interludes in destinations mid-way between Oz and Britain, Ed resigned from Linley and set out for Australia.

When Tonya’s contract at a Sydney hospital ended, they decided to head home for Britain and a life together. But first came a holiday in Queenstown. Ed, who had visited Aotearoa briefly while working with Linley on a super-yacht interior at Auckland’s Alloy Yachts, was keen for a few weeks of skiing.

The Cruikshank children entertain their friends around their father’s Crucible firepit, which can be adapted to changing wind conditions. (From left) Rufus, Orlando de Torres, Sabine Edmonds, Matisse Molgat and Neve.

Tonya, who trained thinking she’d practice obstetrics, was instead attracted by the drama, excitement and camaraderie of emergency medicine. After a little persuasion, she had a three-month contract as a ski-field medic.

It wasn’t long before they asked each other: “Why not stay here?” It was answered with quite a long list of “why nots?”, mostly revolving around their families being 13,000 kilometres away. Distance continues to be the conundrum; all this glorious lifestyle balanced against increasingly aged parents in faraway places.

But then they recall what they love, including their friends, a close community, New Zealand’s education system and, for Tonya, an open society without class structure. And then there’s Queenstown itself.

The lightweight bath by Burmark can be moved outside and is filled using an extended shower fitting. Family members often put it to use on starry evenings. Rufus, however, is happy to pose in the tub any time of day or night.

“I love the openness of the landscape, and I have a sense of being blessed for the opportunity to call this place home,” she says.

Thanks to her recent studies in mindfulness and integrative medicine, Tonya has come to value such emotional currents in her own life and as a way to move her patients into the “green zone”. “Your green zone stimulates oxytocin, and this is deeply healing. All your T-cells rush around cleaning up anything nasty, blood flow goes to the brain and you feel calm and relaxed.”

Willow, the english spaniel, doesn’t understand why humans admire Max Patté’s sculpture of a dog transfixed by the water. She would admire the silent pooch more if it could just stop staring at the pond and join her for a run.

So, for now at least, the family is happily staying put. Ed’s business suits the influx of people to the district. The newcomers are building beautiful homes and need pieces of bespoke furniture that enhance their passion for the region and their lives in it.

Tonya, who always sensed her long-term professional life would be about continuity of care, not just seeing people at their most terrible time, fixing them up and then never meeting them again, is developing her practice into the realm of whole health. And the green currents are flowing.

AT HOME IN THE VALLEY

From the windows of a mountain hut above the Fox Glacier, a helicopter appeared through a small break in a stormy sky. The machine hovered briefly as several skiers tumbled from it into the deep snow, then whirled away steeply, ascending into the fast-vanishing hole in the clouds.

The hut’s occupants cursed quietly as they’d been looking forward to a peaceful night alone during the coming storm.

Every cloud and it’s silver lining … Ed and Tonya Cruikshank found the architect of their dreams that stormy night in the mountains. It was Queenstown-based (and fellow mad-keen skier) Marc Scaife who stumbled through the door. Marc immediately understood the vision for their land in a quiet valley in the Queenstown Basin with views to three mountain ranges.

The goal was to maximize light, space and views. Some 13 years on, the result still delights them. The addition of Ed’s studio across the pond, built four years ago, anchors both buildings to each other and to the site.

ED ON DESIGN

“I couldn’t be less interested in fashion,” says Ed who designs with not just one lifetime in mind but generations.

“If a design is right and well-executed, then it is never out of fashion, and it will remain unchanged forever.”

In recent years, Ed has removed himself from a busy retail shop in Arrowtown to his home studio for the opportunity to design in peace. While he loved the interaction of a bustling small town, he found he was thinking about design in terms of what would sell rather than what he wanted to create.

Most of his work is bespoke, with pieces for private homes as well as corporate commissions. He is currently in his second year creating a significant board table for a large Sydney corporation. The company chose Ed after seeing him embed stories into his work.

Since 2010, Ed has often incorporated braille in the steel frames of his pieces as a kind of secret code between craftsman and commissioner. This started with a commission from art patron David Teplitzky, who invited him to contribute to an exhibition called Roundabout (initially shown in the Wellington City Gallery, then in Tel Aviv).

Ed’s piece, 1821 table, made from 108 pieces of walnut and gun blue metal (paying homage to the 108 invited artists) also incorporated Martin Luther King’s words in braille: “I have decided to stick with love, hate is too great a burden to bear.” In its use of walnut and gun blue metal, traditionally used to make firearms, Ed’s table spoke of peace, tolerance and communication.

“When I feel I am on the right path, I am struck not by a feeling of my skill but of a universal energy and intelligence. When we detect timelessness, we are connecting with this universal matrix. Call it god, or spirit or nature or truth, but it is a fleeting connection with something eternal and beyond description and beyond possession.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.