The Lake Dunn Sculpture Trail: Follow Milynda Rogers’ creative metalwork along an outback Queensland road

An inquisitive kookaburra.

A rural artist is using industrial waste to transform a 200-kilometre loop of dirt road in outback Queensland.

Words & photos: Don Fuchs

Rounding a bend on the unsealed Jericho-Aramac Road in the Queensland outback, I come across a man on horseback. He stands, hat pulled low, gun resting against his shoulder, staring into the heat-shimmering expanse.

The rider is called the Returned Soldier and is not human but sculpture. “I wanted him to have the correct uniform; the gun more like an army gun, not a rifle,” explains its creator, artist Milynda Rogers.

The life-sized sculpture Returned Soldier on top of a bluff is perhaps the most iconic installation along the Lake Dunn Sculpture Trail and is testimony to the artist Milynda Rogers’ understanding of drama.

It’s her obsession with detail that gives this sculpture, made from barbed wire and scrap metal, its sense of reality. Returned Soldier is one of 38 sculptures spread over 200 kilometres of mostly unsealed roads in central Queensland.

Dubbed the Lake Dunn Sculpture Trail (LDST), the route begins in the small town of Aramac, 68 kilometres north of Barcaldine. From there, it forms a generous triangle through cattle country, making it one of the largest outdoor art displays in the world.

Milynda adds the finishing touches to a butterfly.

Milynda, aka Scrap Metal Sheila, is responsible for the sculpture trail, and lives along it with her husband Daryl. The couple also manage Boongoondoo Station, owned by pastoral company Clark & Tait. In good years, they run about 4000 head of santa gertrudis cattle on almost 50,000 hectares.

Butterflies.

The turnoff to Boongoondoo is marked by a sign featuring two metal yellow-crested cockatoos. Next to the homestead is a large open shed.

The shed is Milynda’s studio and contains no easel or brush-filled jars, but metal junk, a large steel table, and welding equipment. More heavy-duty workplace than artspace, it’s nevertheless where all her sculptures originate. Unfinished works are strewn around.

A wild boar.

Milynda (short spiky hair, dark-framed glasses and quiet confidence) came to metalwork relatively late.

“I did sculpture at school, but it was clay and clay-fired,” she says. “When I left school, I focused on painting. It’s only in the past 10 years that I’ve returned to sculpture after seeing some over in Blackall.”

What she saw in Blackall, a “neighbouring” town roughly 220 kilometres south of Boongoondoo Station, was a huge ball made from wire, and a metal eagle made from scrap. “I just loved the idea of using the wire and the old junk to make a sculpture.”

A mythical rainbow serpent.

The beginnings of the LDST were modest and unintentional. “It didn’t start out as a sculpture trail,” she explains. “It began with me putting one sculpture out on the road because I didn’t know where else to put it.”

That was in 2013 and the work, still one of the LDST’s most memorable, is a three-metre-plus bottle tree made of drums, wrapped in barbed wire. Its leaves are tags more commonly found on the ears of cattle.

The dynamic Bronc.

The Returned Soldier is a more recent work and by the time travelers reach it, they’ve already passed three others. The first, just out of Aramac, is a giant red roo on top of a tin shed. On the LDST proper, just after the Jericho-Aramac Road turns from bitumen to dirt, are two easily missed brolgas, crossing beaks like fencing opponents.

Drover, stockman and cattle thief Harry Redford aka Captain Starlight rides into the sunset. The sculpture originally had two dogs but one was stolen.

But the next sculpture, Eagle and Chick, is an eye-catcher: placed on a large rock along the roadside, an eagle looks towards another boulder that holds its nest and chick.

An Emu with chicks.

There are several sculptures on this section of the LDST: Dog on the Rock; the almost invisible Possum in the Tree; two large dragonflies clinging to the windmill tower of a disused well; a deer; and the quirky sculpture Thirsty Cockatoos, a beer bottle made of drums with three black cockatoos on a steel frame and letters forming the words “dry Alice”, referring to the nearby Alice River, which is almost always dry.

It pays to look for the little details in Milynda’s sculptures. They reveal her sometimes-wicked sense of humour. Dog on the Rock, for example. “I just do things to create a little more interest,” she says. “The dog has crystal balls. I just thought, ‘That will give someone a laugh.’”

The dog sculpture (with crystal balls) is just one of the quirky sculptures along the trail.

Besides satisfying her need for a creative outlet, the sculptures also give her joy when they’re sought out. “To be able to make someone smile — that’s why I’ve been so focused on the sculpture trail.”

But the LDST isn’t only about Milynda’s sculptures. Not far from Eagle and Chick, and accessible via a short side track, is the Gray Rock Reserve. There, a sandstone surface protected by an overhanging layer of volcanic rock, is etched with hundreds of names and dates.

This petroglyphic “visitors’ book” was most likely started by coach passengers before the turn of the last century. Traveling from Clermont to Aramac in Cobb & Co coaches, they stayed the night at the Wayside Pub nearby. Only stone foundations and piles of glass shards mark the site today.

- Turkeys.

- Echidna.

- The easily missed dragonfly.

- A three-metre-plus boab tree.

- The White Station Circle, an esoteric installation, was created by an obscure religious society.

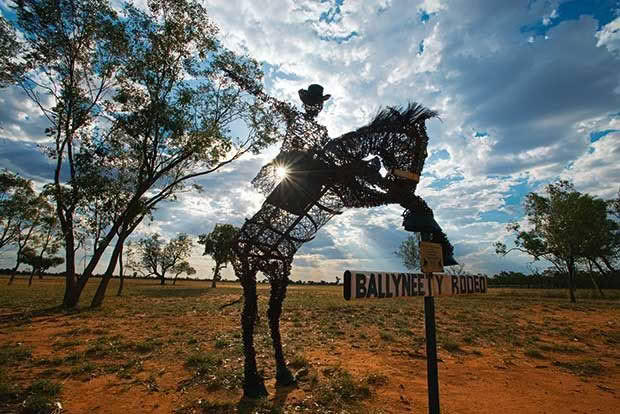

Seventy-seven kilometres after it leaves Aramac, just past The Motorbike Musterer, the Ballyneety Road branches at a right angle. The road forms the next section of the LDST and offers the highest density of sculptures, from an eagle with a wriggling snake in its beak and a gigantic spider lurking in its web, to a plane in a bare paddock with hundreds of termite mounds, and a chopper with a friendly pilot waving at Clare Station.

There are also the dynamic forms of Cutting Horse Cowgirl and Bronc, a tribute to the Ballyneety Rodeo, and one of Milynda’s newest creations, two large-scale butterflies that cling to the smooth trunk of a large gum tree.

Brolgas.

After 65 kilometres of varied open-air artwork, it is, surprisingly, a natural attraction that marks the end of this second section.

Lake Dunn, a large, freshwater lake named after stockman James Dunn, is more than three kilometres long and 1.6 kilometres wide.

The giant spider lurking next to the road is a product of artist Milynda Rogers’ skills and imagination.

A paradise for birdwatchers and anglers alike — golden perch and black bream get the attention here — the lake is also good for watersports, a surprise in this generally dry (even semi-arid) region. A caravan park and simple “beach” shacks cater for visitors.

The third and last leg of the LDST is the 67-kilometre sealed Eastmere Road, which connects Lake Dunn with Aramac. Along this stretch are the trail’s newest additions, erected in December 2018 — a frill-necked lizard, an impressive ram and a representation of league legend Johnathan Thurston.

A goanna.

Beside the Rainbow Serpent is the turnoff to a more curious attraction. Called the White Station Circle, it consists of knee-high stones laid out in a large circle seven metres in diameter. Inside is a smaller circle with a cross in its middle that its creators — the religious organization Foundation of Heaven — claims represents the eye of God.

Two Thirsty Cockatoos.

The last 30 kilometres of the LDST still has plenty for sculpture-lovers. There are birds, including the giant jabirus and a few stocky turkeys, as well as local legend Harry Redford, a drover, stockman and cattle thief famous for stealing a white bull.

“I want to have a white bull somewhere,” Milynda says. “There’s an old white car down at the dump, and I’m going to make it out of that.” She also plans to create a life-size sculpture of pastoralist and explorer Nat Buchanan.

A wedge-tailed eagle with nest.

“He used to ride a horse, and he had two camels and a green umbrella,” she says. “That’ll be a perfect sculpture.”

NOTEBOOK

Getting there: From Rockhampton, it is a 670-kilometre drive on sealed roads to Aramac, the starting point of the LDST. A 4WD vehicle is essential.

Road conditions: The trail is unsealed, except for the section between Lake Dunn and Aramac.

Fuel: Only available in Aramac.

Where to stay: Although the LDST can be done in one day, it pays to take a slower pace. Accommodation is available in Aramac (basic motel) and — if camping is an option — on the shores of Lake Dunn.

When to go: The cooler months of June to September.

More information: A map of the LDST can be obtained at the council offices in Barcaldine.

MORE HERE:

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.