Ōpōtiki artist Fiona Kerr Gedson transforms feathers into Nepal-inspired mandalas

A compass is used to sketch concentric lines around an empty canvas. “Every feather is measured to ensure the circles are correct.”

This Bay of Plenty artist fastidiously creates her feathered art, placing plumage perfectly — just as it is in nature.

Words: Cari Johnson Photos: Brennan Thomas

Ōpōtiki artist Fiona Kerr Gedson sweeps a line of opalescent grey around a circular canvas. Next, she blends a pop of electric blue seamlessly into the grey. She doesn’t work with paint but feathers, carefully glued one by one to create a 60-centimetre mandala.

From a distance, Fiona’s mandalas look solid, the plumed details only coming into focus closer up. Featherwork is a technique she’s been fine-tuning for 21 years and is inspired by kahu huruhuru, or traditional Māori cloaks.

Fiona works alone in her home studio, sometimes deep into the evenings. “Feathering is where I’m happiest. It’s like I meditate my way through creating a piece.” A trip to Dunedin inspired the mandala, called Port Chalmers — Homage to Hotere, behind her. She spent a day at Port Chalmers with her sister, Melanie Kerr, jeweller Debra Fallowfield, and artist Mary McFarlane (Ralph Hotere’s widow) before returning home to create it.

“Kahu huruhuru hold a lot of mana. I hope my featherwork holds some of that and honours its origin.”

But instead of using the native bird feathers used in traditional craft, Fiona uses ethically sourced feathers from introduced birds. Turkey and pheasant are her neutral bronzes and graphites, while peacock and speckled guinea fowl feathers provide dimension, texture and geometry.

- Fiona’s piece, The Geometry of Human Connection has a peacock-blue diameter and single quadrant filled with speckled guinea fowl feathers.

- A feathered piece from Fiona’s Kerr Tartan collection, a Scottish-inspired pattern that she explored after returning to her maiden name.

- The artist strayed from her usual mandala with her tekoteko-inspired piece Pou Whirinaki, which translates to a pillar of support or dependable post to lean on.

The artist can’t put her finger on the moment her award-winning creations caught on with local and international art-lovers. Her sister Melanie says it happened “slowly, slowly, slowly — overnight”.

But Fiona certainly got lucky when Pauline Bianchi (who featured in NZ Life & Leisure, May/June 2017) came across her work. The director of Queenstown’s Artbay Gallery commissioned the artist to make a rectangular piece more than a metre wide, nearly 10 times the size Fiona was used to.

Despite fine-tuning her craft over two decades, Fiona feels there’s still room to grow. “It feels like I’ve completed my apprenticeship with feathers. There’s so much more that I can explore to express myself”.

“It blew my mind. I’m sure my work would’ve progressed, but that commission helped me leap forward.” Fiona’s works are now sold at Artbay and in several other galleries nationwide.

The mandala is Fiona’s oeuvre, although she sometimes breaks her own rules. She once transformed a greenstone tiki into a feathered piece, and her collection of feathered tartan and Celtic knots would make her Scottish ancestors proud. But while the use of feathers is undeniably rooted in Māori culture, Fiona doesn’t have a drop of Māori blood.

“With its large Māori population, Ōpōtiki has strong Māori influences in everyday life. It’s our culture, really. You can’t extract Māori culture from life here,” she says.

She has lived in or around the small, dune-studded coastal town since she was a teen. She married at 18 and Ōpōtiki became home for her and her husband — she raised her four children (of Whakatōhea iwi on their dad’s side) on the family farm. She wouldn’t change a thing from her past.

Fairren peeks over the edge of the mezzanine (also her bedroom) that overlooks the kitchen. The glass lampshades were among many op-shop finds Fiona hoped would give her home a vintage touch. “I hung them over my table, but my son Braden would always bang his head on them, and he wasn’t the only one. I came home one weekend and discovered he had used cable ties to shorten them. Since he at least used white cable ties, I left them.”

“I was physically grounded because of the kids. Being at home with my babies allowed me to develop my work from that space,” she says.

The couple’s marriage ended after 17 years, which was painful, but leaving the home in which she had raised her family was particularly so. “I didn’t realise how much of my identity was tied to that place. I lived there for 20 years and thought I was going to be an old lady there. But circumstances change.”

- A 30th birthday gift hangs behind Fiona and Niamh in the kitchen. The loose black canvas, made by Felicity Barry, includes words from a poem Felicity’s daughter Sylvia Quant wrote for her. “I used to have it like a blind in the farmhouse and rolled it up and down by hand every day. After moving here, I squealed with delight when I realized I had a wall big enough to hang it on”

- The Tibetan prayer flags outside Fiona’s home are a nod to Nepal. The flags are a souvenir from her and Fairren’s pilgrimage to Nepal last year, exactly two decades after her first visit in 1998.

- The blanket beneath Fairren has the illusion of a korowai, but is a throw Fiona received from her aunt for her 40th birthday.

She decided there would be few compromises with her next home. Three years ago, during construction of the 130-square-metre house, she assembled a small collection of possessions. Each piece had qualities she hoped would add character and warmth to the property’s freshly milled timber and glossy black exterior.

“I didn’t want the house to feel new,” says Fiona. “I wanted it to have character and soul.” She adores just about everything down to the last doorknob. In Fiona’s world, the smallest details convey the most powerful messages.

Today, she balances family, art, a non-negotiable daily walk with her son’s dog Taz, yoga and meditation. The home itself is full. Daughters Fairren (15) and Niamh (19) live with Fiona and sons Rory (23) and Braden (26) visit when they can. Her ex-husband’s two-year-old twins, are also embraced into the whānau. There are no half-siblings in this family.

The hanging feathered cloak combines Fiona’s weaving and featherwork. This piece, made with ostrich feathers (to emulate kiwi feathers), was a gift for Niamh when she was born. Waikato artist Ron Hall constructed Still Waters (hanging below the cloak) from recycled beehives, and Cheryl Oliver made the figurine on the table.

She feels blessed in this slice of Ōpōtiki and, due to the proximity of a sacred site, possibly even destined to be here. An urupā (cemetery) next to her home is the resting place of two female Māori, discovered (and reburied) long before Fiona moved here. She feels close to them physically and spiritually.

Fiona’s bedroom looks nothing like the rest of the house. “It’s like a cave. When I pull my curtains, it becomes dark and delicious. I wanted a completely different feel from the rest of the house,” she says.

“Whenever I got anxious through the build process, I’d imagine those females were looking after me, that everything was going to be fine. I feel incredibly privileged and honoured to be able to care for this space. Living here is now a big part of who I am.”

Fiona, with whānau and feathers, is exactly where she’s supposed to be.

FROM PESTS TO PERFECTION

Fiona learned her technique from kuia (female elders) at a Gisborne A&P Show.

While harakeke (flax) weaving was more prominent in her earlier works, her intricate featherwork is also rooted in Māori technique.

The tiny turkey, pheasant and peacock feathers would be impossible to pick up without tweezers.

Like many modern artisans, Fiona uses feathers from introduced birds such as turkeys, pheasants and peacocks. Peacocks, prolific around Ōpōtiki, are considered pests and Fiona is often gifted carcasses from farmers.

“I skin the birds myself, which is not a glamorous side of my job. Depending on the state of the birds, I’ll give the meat away or to the dog.” She also buys feathers from Whakātane couple Dave Barrett and Mawera Karetai, whose pelt and feather business Feathergirl helps with pest control without resort to poisons.

MAD FOR MANDALA

A trip to Nepal in 1998 was significant for Fiona.

“Nepal is where my mandala comes from, and it’s where I started to explore my spirituality. It was the start of my life as I know it now.”

She first trialed the mandala in New Zealand after seeing Tibetan monks make a sand mandala at the Whakatane Summer Arts Festival (where she was a guest exhibitor).

“My first feather mandala felt right, and the materials just came together. The circular design has so much scope for diversity within it,” she says.

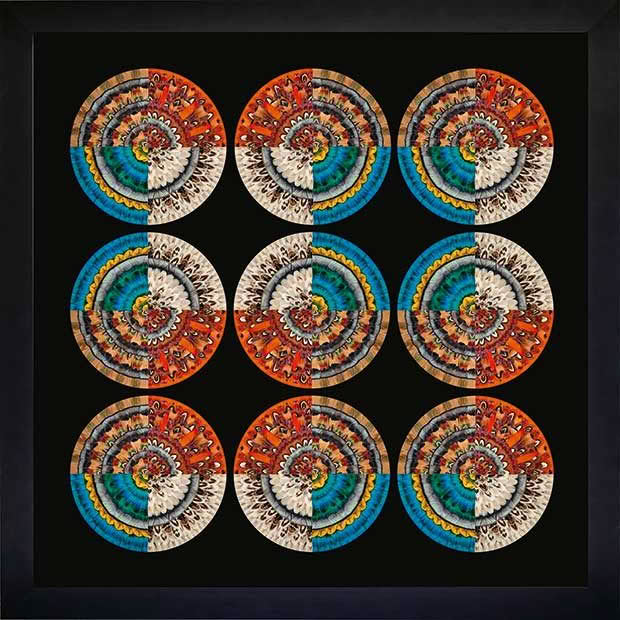

The Geometry of Human Connection.

Mandala translates as “circle” in Sanskrit and carries many spiritual definitions, including the Tibetan Buddhist notion of emitting positive energy to the people who view them.

Fiona has made the mandala her own with elements of geometry, like highlighting quadrants with contrasting feathers and even splicing it into pieces or spirals for a kaleidoscope effect.

“I hope anyone who engages with my work can find some relaxation, a little moment of relief. Since mandalas are used for meditation, I hope people feel a release like you get from meditating.” fionakerrgedson.com

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.