The Kiwi connection at Wardington Manor: How two women are revolutionizing cut flowers in Britain

Designing duo Bridget Elworthy and Henrietta Courtauld create living, breathing gardens that strive to be healthy from the ground up.

Words: Lee-Anne Duncan Photos: Michael Paul

A tour through the gardens at Britain’s Wardington Manor is a gentle stroll through the seasons.

“We pick from the orchard all year round,” says owner Bridget Elworthy. “In the winter, we start with snowdrops and crocuses. Then we pick apple blossom, fritillarias, camassias, daffodils and narcissi in the spring, followed by cow parsley and oxeye daisies in early summer, rambling roses in late summer and boughs of fruit in the autumn.”

Blooms from Wardington Manor’s garden – coral charm peonies and David Austin heritage roses. “Peonies are used in Chinese medicine, so we’re researching the idea of growing peonies and other herbs for medicinal use,” says Bridget.

“In early spring we’re down at the Pond Walk, where the rhododendrons, magnolias and camellias are out,” says her business partner, Henrietta Courtauld.

“Then we pick tulips from the long tulip borders in spring, then up to the iris borders for scillas in March and irises in May. The herbaceous borders and cut flowers come into their own in summer. Finally, in autumn we go over to the dahlia borders, and back to gathering bulbs from the Church Walk in winter.”

“It’s like conducting an orchestra — as things pop up, we go to that part of the garden and give it attention. It’s a lot of fun,” says Bridget, who, while she now has an Oxfordshire postcode, grew up on a farm in South Canterbury.

Rosa ‘Cecile Brünner’ and deutzia are arranged in the flower room at Wardington Manor. As well as designing walled and productive gardens, The Land Gardeners supply flowers for special events and to selected clients. The flower room’s walls are lined with dozens of vases, jars and terrines for their arrangements.

Bridget and Henrietta together are The Land Gardeners, a garden design and cut-flower company set up in 2012. That’s some years after the two designers met when their now-18-year-old daughters became friends at nursery school. Both are former lawyers. When Henrietta — who grew up in Kent — found herself doodling gardens at the back of the courtroom, she gave up the law to work in a plant nursery, then studied garden design.

Bridget, who says she’s “done many things badly”, earlier ditched law to study design, but was drawn to “growing things” when living in France with husband Forbes. Then, as she and Forbes were due to move back to New Zealand to take over his family’s South Canterbury farm, Craigmore,

Wardington’s peonies are originally from Craigmore Station in South Canterbury. Forbes’ mother, Fiona Elworthy, first imported peonies to New Zealand in the 1980s and, with daughter Eve, began growing them at Craigmore and exporting them around the world. The walled garden is abundant with vegetables, fruit and flowers — restoring walled gardens is another of The Land Gardeners’ specialities.

Bridget began studying horticulture at the English Garden School. Like Henrietta, she went on to study garden design.

In 2008, after three years running the farm, the Elworthys moved back to England, and four years after that, Bridget and Henrietta started their business.

“With our name, we wanted to evoke the amazing women who turned the land during the war — The Land Girls — and we wanted to capture the feeling that, although we design, we are gardeners,” says Henrietta, who loves to anthropomorphize plants and can spell most every Latinate name from memory.

- A view from a bedroom through a Magnolia grandiflora onto the Top Lawn’s buttress borders.

- “We train the magnolia against the walls. It’s great for foliage in the winter as it’s evergreen,” says Bridget.

- A sweep of sweet irises.

“It doesn’t matter how much you study; you can only really know about plants by gardening with them. You must know how they feel, what their roots are like, and when they burst into growth. You need to know their characters and how they work with other plants — whether they are bullies or are delicate.”

The duo’s studio is in London’s Notting Hill. But Bridget and Forbes’ 15th-century home has given them the perfect base to grow their consultancy, their cut-flower business, and — most latterly — their “climate composting” project. It’s all achieved with a determination to revolutionize how people garden, boosting health and creating balance both below and above the soil.

Bridget Elworthy walks between the dahlia and tulip beds towards a yew topiary “room” planted in the Edwardian period. Each autumn the dahlias are dug out and replaced by about 12,000 tulip bulbs. When the tulips are finished, they’re dug up (to avoid the possibility of the fungal disease, tulip fire) and used as compost, and the dahlias planted back in. “It requires attention twice a year, but otherwise it is fairly low maintenance gardening, providing us with incredible joy and colour in spring and autumn,” says Henrietta. “It is unlike a herbaceous border, where you are constantly looking at the needs of the different plants.”

Wardington Manor, behind its centuries-old high stone walls and iron gates, lies at the heart of a beautiful, rambling garden. A series of Edwardian garden rooms weave around the ironstone walls and high yew hedges. It’s wild and romantic, with an abundance of blooms.

Sometimes parts of the lawn are allowed to grow long, much to the delight of insects who flit about in the knee-high self-seeded wildflowers and herbs. “

- Bridget’s hens are welcomed not only for their compost but for their skills at keeping down slugs, caterpillars, snails and ants.

- “In winter we move them to the walled garden, so they eat the slugs’ eggs,” says Henrietta.

- “People only start thinking about slugs in spring, but if the hens can get their eggs through winter, you’re ahead of the game.”

If we’d mown it, there’d be nothing there,” says Bridget. “It’s good to let things grow wild, and it’s fun to see what’s growing in there.”

Whether it’s grown in the herbaceous borders, the walled garden, the orchard, or the polytunnel in the cut-flower garden across the road from the manor, everything is productive not just pretty. Vegetables are often allowed to go to seed — leeks with their softball-sized boule heads, parsnips’ bright yellow blooms, and asparagus with their delicate filigree fronds. All of these flowers are offered to clients.

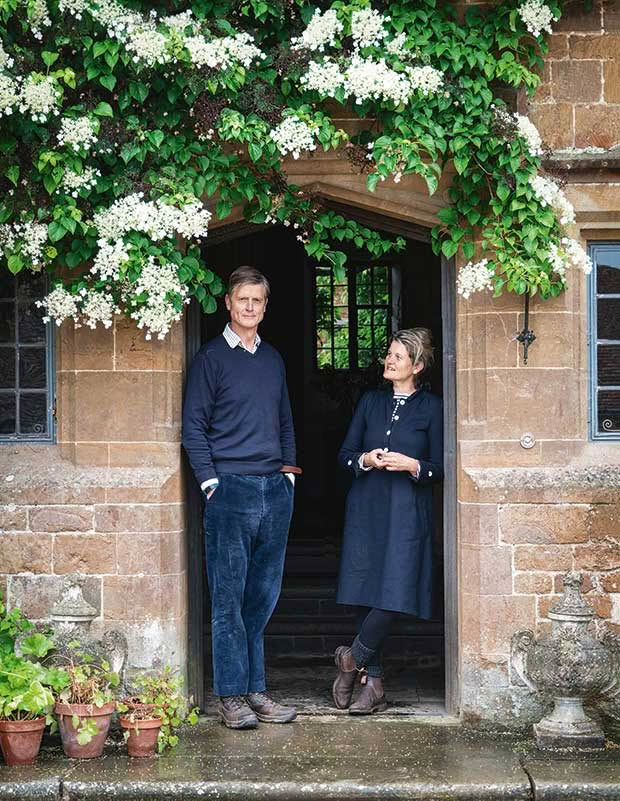

Forbes and Bridget stand in the front doorway of the manor, under the Hydrangea petiolaris. “We pick this climbing hydrangea a lot. It has such lovely white lace flowers,” says Bridget.

“We’re always picking. This morning we were picking scabious from the herbaceous border, and next week the white phlox will appear,” says Bridget.

“We’ve found the more we pick from the borders, the more the plants like it,” says Henrietta. “It’s like live pruning — the plants become more vigorous, and we get more and more flowers. So, we’re always climbing to the back of borders and bringing out armfuls of things.”

In the flower room, poppies, peonies and roses bear the scents and colours of early summer.

Those “things” become flowers The Land Gardeners supply for use at local and London-based events and to a few select florists. These include Prince Charles’ florist Shane Connolly, who designed the flowers for the weddings of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and the Prince of Wales to the Duchess of Cornwall.

Farmed flowers may offer uniformity of shape, and longevity due to the heavy use of agrichemical sprays, but cut flowers from a garden offer something else, says Henrietta.

The library’s 17th-century panelling needed serious repair after a fire in 2004. The large original fireplace is lit most of the year, even in summer, for atmosphere as well as warmth.

“They’re like people; they each have their own story. They have a lovely character and movement to them. You buy stiff flowers from a shop, but flowers from a garden are often lovely and arching and almost dance in the vase. And they have an incredible scent you don’t get from farmed flowers.

“However, ours don’t always last as long because we grow organically and don’t spray. We have had to educate our customers about that. But there’s beauty in a dying flower — in a rose’s drooping petals or a tulip’s last burst of colour.”

- Rosa ‘Alba Maxima’ in a vase sets off the astounding and extensive plasterwork added in the 1920s by the Arts and Crafts craftswoman, Molly Wells.

- The 1920s plasterwork extends up the stairs. It shows designer Molly Wells’ sense of humour and includes a menagerie of characters, real and imagined, among its more traditional chevrons.

- The staircase dates from the 17th century.

- A guest bedroom (opposite, top right), which Henrietta often uses when she stays. When Bridget found it, the four-poster bed was in parts and had to be “knocked together”.

- The kitchen was added when Bridget and Forbes bought the manor.

- Another angle of the kitchen.

The controlled chaos of the quintessential English country garden — or, perhaps, its expertly conducted chorus — suits Wardington Manor down to its foundation stones. It was built as a nunnery on 1450, then extended in 1665 and renovated (beautifully) in the 1920s. In 2008 Bridget and Forbes bought it with their three children, now aged between 13 and 20.

After the three years they had just spent at Craigmore “going to a country school, climbing trees and riding ponies”, Bridget and the children had no desire to live in London again, and wanted to live in the countryside. Wardington suited them fine.

The bronze bust is of Bridget and Forbes’ daughter, Violet (now 18), by Dutch/New Zealand artist Margriet Windhausen who asked Violet, then nine, to sit for her. Margriet used to live behind Craigmore.

The manor had been restored after a fire in 2004. Most of the house escaped the flames but there was plenty of water damage, so the 17th-century panelling was taken out, repaired, and restored.

“The restoration was a long job, and Audrey, Lady Wardington, did all the hard work. When we got here, the fabric of the building had been beautifully restored, so we’ve had to do very little,” says Bridget.

A Frances Palmer (an American potter) vase in the library.

Outside, however, Bridget and Henrietta have done a lot, re-invigorating the various flower beds and garden, all with close attention to what’s going on underground.

While at Craigmore, Bridget did a lot of research and work on organic and biodynamic farming, following the teachings of Kay Baxter, one of New Zealand’s best known organic gardening pioneers. Thus, the pair’s focus is very much on improving soil health to benefit the health of pretty much everything.

Roses and peonies are arranged in a soup terrines, along with Euphorbia oblongata (in bowl on the table behind). “Euphorbia oblongata is good for summer foliage as it flowers all summer long,” says Henrietta. On the wall are pressed 18th-century Jamaican ferns.

“Getting the soil health right makes the plants more nutrient-dense,” says Bridget. “Healthy plants means healthy animals, humans — and ultimately — a healthy planet.

In the pantry, the seaweed prints were a present from New Zealander Charlie McCormick. A bucket of peonies grown from Craigmore cuttings is on the dresser.

“Years of ploughing and mismanagement has degraded our soils and the life within them,” she says.

“If we are to improve the health of humans and our planet, we need to nurture the microbial life within the soil to produce healthy, nutrient-dense vegetables and to sequester carbon from the atmosphere.”

Forbes and Lenka Freharova outside the flower room, about to go for a ride on polo ponies. “Lenka is a great cook and helps with our garden workshops,” says Bridget.

“It’s about creating a living garden,” says Henrietta. “You can go into a beautifully aesthetic garden, but it doesn’t hold you because it’s been sprayed to the nth degree. It’s sterile, and there’s no noise.

“We create gardens that feel alive, that are about the birds and the insects, and all the tiny animals in the soil. Gardening isn’t just about creating something that looks fabulous but has no balance — gardening is about nurturing the life both above and beneath the ground.”

Bearded irises and foxgloves in the walled garden outside the potting shed.

PICKING FOR LIFE

While cut flowers from a garden may not last as long as farmed flowers from the supermarket, there are ways to prolong their beauty. Here are Bridget and Henrietta’s tips:

Rose weather better in the cool of the flower room.

* Pick in the cool of the morning or evening when there is less transpiration, and dunk in water immediately.

* Then sear the stems by placing them in boiling water — about 10 seconds for a delicate stem or up to 40 for hard stems, but basically until the bubbles stop. Place in cold water “up to their necks”.

* Ideally, arrange the next day — Henrietta says flowers “seem to like to sit in a dark spot and gather themselves” for a while.

* Keep the room as cool as possible.

Most loved flowers for cutting:

Daphne

Snowdrops

Tulips

Blossom, apple and cherry

Magnolia x soulangeana and Magnolia stellata

Foxgloves

Sweet rocket

Iris

Peonies

Delphiniums

Queen anne’s lace

Sweetpeas

Roses

Astrantia

Euphorbia oblongata

Iceland poppies

Cosmos

Dahlias

Paperwhites

COMPOSTING FOR THE CLIMATE

The Land Gardeners have been working with a local farmer, trialing ways to create “climate compost” on a large scale. They then plan tosell it to other farmers and gardeners. It’s called “climate compost” because it enhances the microbial life in the soil which, along with plants, improves the ground’s ability to sequester carbon, benefiting the environment.

Rhett Goodley-Hornblow, a friend from New Zealand, carries an armload of parsnip in flower.

“We use a system of windrows where we layer carbon (straw, dead leaves, stems, cardboard), nitrogen (grass clippings, weeds, green matter, manure) and clay,” says Henrietta.

“We measure the oxygen levels and temperature — so by ensuring there’s the correct oxygen, heat (between 58 and 65 degrees Celsius) and moisture we encourage rich microbial life.

“Many of the composts people buy are just organic matter, but they’re dead with no life in them. We are trialing ways to make high-quality, microbially rich compost in six to eight weeks that we can sell.

“And we aim to teach people then to make their own, even if they have quite small-scale gardens.”

Bridget cuts Ammi majus in the polytunnel. “We grow flowers in the polytunnel to extend the season. We bring them on so they flower earlier in the spring than outside in the cutting garden”.

Says Bridget: “We’ve also been trialing how to make compost teas, which are good for scaling up for large farms. You put compost into a muslin bag and then into a compost tea maker — it’s like a bubbling pot that has air forced into it, like an aquarium. It’s brewed for 24 hours, and then you spray it on in the evening — or when it’s dull, as sunlight kills microbes.

“And it is essential to cover your soil with plants or green manures. The soil microbes live symbiotically with plant roots, and their existence is thus dependent on them.

“We also practice a minimal till in the garden, only aerating the soil when necessary to avoid disturbing the microbial life.”

The Land Gardeners are headline speakers at Rapaura Springs Garden Marlborough on 7 to 10 November. On Friday evening, they will reveal how they developed the gardens at Wardington Manor. On Sunday morning, they’ll speak about the cut flowers they grow throughout the year. Tickets on sale at gardenmarlborough.co.nz

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.