A little house on the apiary: Beekeeper Nathan Orr’s tiny house passion stemmed from a teenage illness

Nathan Orr’s enthusiasm for tiny homes and leaving a smaller footprint on the planet is rooted in a teenage illness

Words: Venetia Sherson Photos: Tracey Robinson

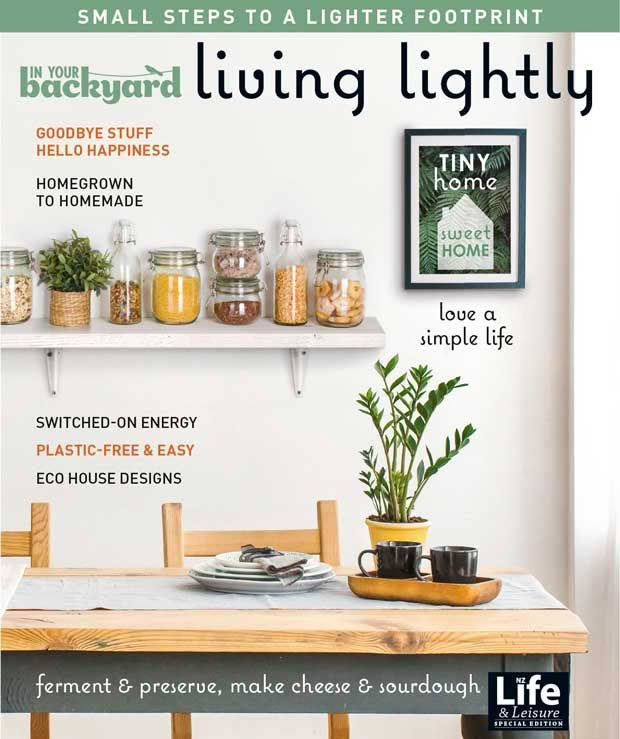

This story is an extract from the special edition In Your Backyard: Living Lightly order before

When Nathan Orr moved from the Waikato to the Bay of Plenty to take up a new job as a beekeeper, he took his house with him.

The 32sqm house was loaded onto a trailer in October last year and, as dawn broke, towed 127km across the Kaimai Ranges from Hamilton to its new site on the outskirts of Te Puke.

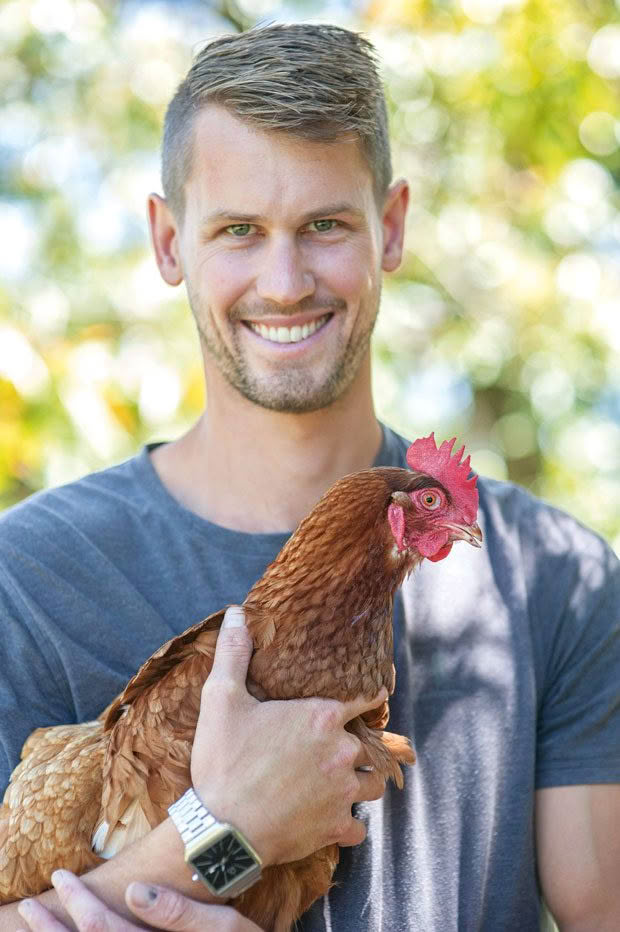

Nathan’s chickens are named after philosophers to remind him to consider new and seemingly outlandish ideas every day. The bird pictured is Aristotle. The breed is Hyline, known as good layers.

The tiny house is a practical solution to accommodation for the 29-year-old who admits he doesn’t know where his work will take him in the future. More importantly, it’s a metaphor for the way he wants to live his life.

“The house represents all the things I have been thinking about: how we currently live; how we should live; what we need as opposed to what we want and the way we look after the planet.” It’s a philosophy sharpened over years of research, work and travel. But it had its beginnings in a dark year a decade ago.

Nathan left St John’s College in Hamilton in 2008. He says he was a shy kid, dyslexic and “not suited to the school system”. He enjoyed sport and was good at it, but he had no idea what he wanted to do. He took a gap year to make up his mind.

Nathan Orr’s tiny home is nearing completion nearly 18 months after he began the project. He says “life” got in the way of completing it earlier, plus he has several other projects on the go, or in the planning stages, including his full-time job as a beekeeper.

The following year, fate intervened. He was diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare cancer that starts in the bones or soft tissue around the bones. To prevent the cancer spreading, he underwent 14 rounds of chemotherapy, and surgery to remove his right femur and three of four muscles in his thigh.

Recovering in hospital, he talked to older patients and was struck by how many wished they had spent more time focusing on family and friends rather than material possessions. It got him thinking. “It was a tough year, but it helped shape a better person than I was on track to be.”

His studies at the University of Waikato solidified his thoughts. He gained a bachelor’s degree in communication, majoring in marketing and public relations, and a master’s in management studies with a focus on sustainability. He was awarded two prime minister’s scholarships to study at the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade in New Delhi, the world’s most polluted city, and the South Western University of Finance and Economics in Chengdu, China.

Nathan at work at the apiary.

His thesis considered the sustainable practices of New Zealand businesses, in particular the way those businesses capitalized on the image of sustainability to enhance their reputation.

“There was a lot of greenwashing,” he says, a term used to describe businesses that painta green picture of their enterprise for commercial advantage. He was saddened by that but saw it as an opportunity to demonstrate that good practice leads to good business through enhancement of reputation. Adhering to Gandhi’s fundamental philosophy that an individual must be the change he or she wants to see in the world, he also began to effect a transmutation. He swapped his suit for work boots and built a tiny house.

Tiny houses are the manifestation of a worldwide movement that has developed in response to environmental and financial concerns, as well as a desire for simplicity and freedom. As house prices rise beyond the budgets of many families, tiny homes — any residential structure smaller than 40sqm — offer a cost-effective and ecologically sound alternative to five-bedroom mansions.

Most are built on trailers, so they can be defined as vehicles under the Transport Act rather than buildings under the Building Act, thus avoiding many of the expenses of building compliance. However, they are generally built for permanent living.

In New Zealand, the tiny-house movement is growing as more people become sold on the benefits of living smaller and consuming less. Nathan is one of them and he wants to make it easier for others. He is a tad under 2m tall. (“I’m an ambassador for tall people living small.”) That’s a large frame to fit into a home 8m long, 2.9m wide and 4.28m high. But he says his house is perfect for his needs.

“I had to consider my height, so functionality was a primary design principle.”

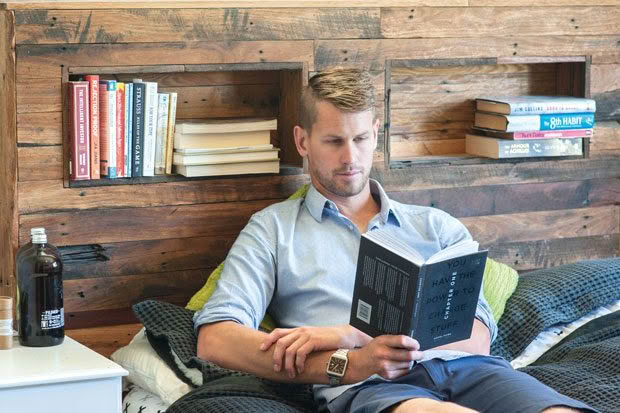

Nathan says his tiny home will have everything he needs, including space for books that stretch his imagination in new ways.

He also needed ease of accessibility. “Many of the tiny homes I’ve been in require crawling around a loft to get into bed or folding half the house away to make a coffee in the morning. It was important to have a house that looked and functioned as a conventional house, just much smaller.”

He says when people enter his tiny house, they don’t see cramped space. “I wanted people to know anyone can do this. When they walk in, they see a full-sized shower and kitchen; the house is wired for fibre; there are spots for television sets and tonnes of storage.

“I started with the question, ‘How much stuff do I need?’ and built the space accordingly.” He says he has felt more cramped in poorly designed apartments. While floor space is limited, Nathan has not compromised on quality. But at some point ideals and pragmatism eventually butt heads. The maximum allowable weight for a transportable tiny home is 3.5 tonnes, including the trailer.

Beekeeper Nathan Orr’s tiny home moves to where his work takes him.

“Every item is considered by need and weight. If I wanted to put in a granite staircase, it would simply weigh too much. Decisions are made on cost, weight, sustainability, longevity and ease of construction.”

Like many of his generation, he says buying a full-sized house and section was out of his financial reach. But he also has no wish to do so. “Between 1990 and 2010, house sizes increased from an average 132sqm to 205sqm, while there has been a 20 per cent reduction in occupants.

“We buy too much stuff then work far too hard to pay for it. With two working parents, often the kids miss out. There are losses of generational friendships between grandparents and children. We build 2m fences between our houses and never know whether our neighbours are unwell, lonely or need a cup of sugar.”

Nathan tries to grow his own food.

He says tiny houses are a move in a new direction, but they also take what was good from the past, including community connections.

In building his own tiny home, he was confronted by another issue: where to put his house. “If you don’t own land — and that is also a huge cost — you have nowhere to set down roots.” To solve the problem, he set up LandShare (landshare.nz) to help Tiny Homes on Wheels (THOW) owners find land to park their homes on.

The idea is based on other models such as Uber and Airbnb, in which existing assets (privately owned cars or homes) are shared. LandShare puts landowners who would like to rent part of their property in touch with tiny-home owners who want a place to put down their trailers. It’s rather like a dating site, with listings posted under “tiny house looking for land” or “land looking for tiny house”.

At the time of writing, the listings included: a backyard for rent in Sandringham, Auckland; a couple wanting a place to park their tiny home for a year near Whakatane; and a family of four wanting a long-term lease on a rural property near Hamilton. There are more people after land than offering it, but Nathan is hopeful that will change as word spreads. He says the scheme holds benefits for both parties.

“For farmers, for example, it provides additional income that could provide a buffer against downturns. It’s like having bees on your property or developing a tourism venture as a sideline. It’s a different and practical way of making the most of the land you have.”

Most tiny homes are pretty much self-contained. They have composting toilets and operate off the grid, so they only need access to water. The average weekly rental is about $80 to $100.

Nathan says there’s a misconception that tiny-home owners are alternative folk who make dandelion tea; they are a varied community, including single mothers, millennials, young families and older adults downsizing or wanting to be closer to families. “Some are alternative, others not. They are just people who want to do something that suits them best.”

His own home is parked at his workplace, where he manages a commercial beekeeping business for a kiwifruit grower. His previous job was business development manager for the Waikato Chamber of Commerce. The bee job appealed because he is interested in bees as a potential business. But also because of the relationship bees and humans share for survival.

“I’m interested in my responsibility as a person on the planet — to understand how that relationship works and how we need each other. It’s not enough to just exist.”

HOUSE RULES

What was the biggest extravagance in the build? “By far my time. People never talk about the time it takes to build. Time is money. I thought it would take me three months; it’s taken me about a year. I also took some time off work. The trailer cost $13,500 because I went for the high end. This way you get quality and longevity. I wanted to tow it anywhere safely. I didn’t want any rust or warrant issues.”

What would never be seen in a house owned by you? “Wasted space. You need to think about the layout of everything. If you want a particular space for a chair or a cupboard or stairs, you design it to make it fit. Every area is used. In a conventional house, we live in 20 per cent of the space 80 per cent of the time. A tiny house is about 20 per cent of a traditional home, so you need to use all that space.”

Biggest inconvenience? “Difficulty with the council and the need to build on a trailer to avoid regulatory restraints. Given that New Zealand has a shortage of affordable housing, you’d hope regulations would be a bit friendlier.”

Favourite thing in the house? “I can stand up in my loft. Most lofts only have crawl space. I wanted to be able to walk around.”

Advice for newbies “Go and see a tiny house before you design, build or buy. Look on Airbnb. There are houses you can try before you buy, which provide ideas that might work for you. Once you’ve done that, you can look at some cool house designs.”

HOW IT WORKS — LandShare.nz

How many people are involved; what percentage want land as opposed to people offering land?

“The website has had 80,000 views; there have been 754 advertisements in the past year and 2064 registrations. About 60 per cent have wanted land to rent while 40 per cent have offered land, although it does swing back and forth.”

Demographics and motivations of people contacting you?

“It’s a mixed bag — millennials and single mums are a big part of the group. There are people from overseas who can’t afford to get into the housing market, and elderly people downsizing. They are motivated by sustainability, price and transient styles of living. People often want advice on regulations and referrals for builders.”

What are the benefits to land sharing for landlords and tenants?

“For landlords, it is monetizing unused or under-used land assets; for tenants, it’s a place to live that doesn’t necessarily involve buying land. There are broader philosophical reasons that may have to do with a greater sense of community, collaboration on projects such as gardens, plus shared resources.”

Any downsides?

“Evictions and disputes are possible as with any tenancy arrangements. From the outset, there needs to be a legally binding tenancy contract, which is a written version of what both parties hope to get out of the arrangement and their roles and responsibilities, e.g. period of notice to end the agreement, guests, pets and parking. Sound decision-making at the start can avoid problems.”

What’s your vision for LandShare.nz?

“I would like it to broaden its scope and look at how we utilize assets. We could think about things we don’t use a lot and how we could share them. If it’s part of the solution to housing affordability and a massive waste of resources, that would be a win for me.”

For more tiny house, green living and eco ideas see our special edition, In Your Backyard: Living Lightly

READ MORE ON TINY HOUSES

Japanese Furoshiki: An eco-friendly alternative to paper gift wrapping