Creating Disneyland in Whitianga: How one man’s ‘mad’ search for the lost spring of Taputapuatea paid off

Most people avoid getting into hot water, but the creator of a Coromandel resort spent two decades, and many millions of dollars, drilling for it.

Words: Nicola Martin Photos: Tessa Chrisp

“From passion to madness,” suggests Alan Hopping imagining the title for a book, should one ever be written about his life.

In 1983, the then-Karaka dairy farmer sold his land to purchase a holiday camp one street back from Whitianga’s Buffalo Beach on the Coromandel Peninsula. Alan was an unlikely candidate to run a holiday camp despite his determination to do so. He is the eldest of five siblings from a family of dairy farmers originally from the Hauraki Plains, then Karaka. But dairy farming was not for him.

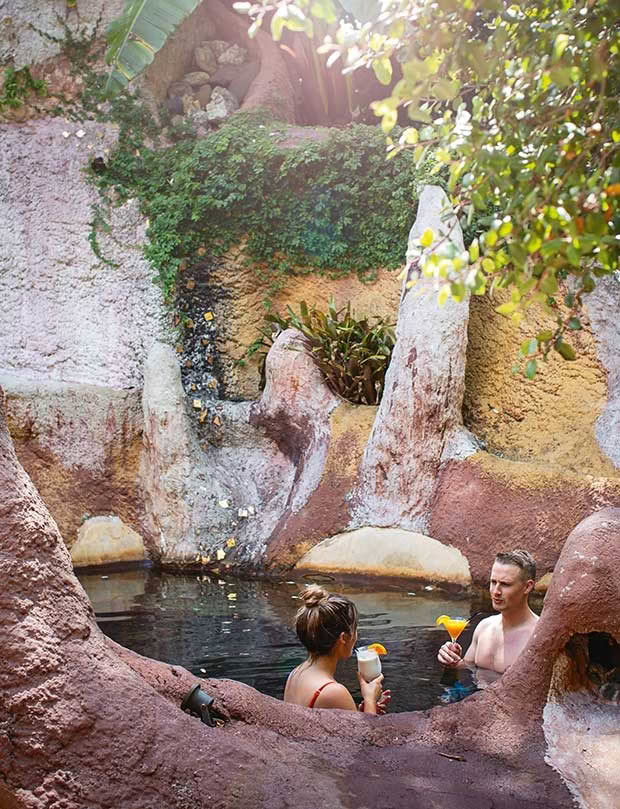

Hot water flows through The Lost Spring’s system of pools, all of which are connected. From the hottest — Crater Lake, which sits underneath the Volcano — down to a cavern called the Grotto, and finally spilling out into an area known as the Bath Tub. Owner Alan Hopping says he created nooks and corners throughout the complex to allow guests a feeling of seclusion.

“Farmers were receiving government subsidies in those days. Our lives were subsidized by families living up the road in Pukekohe. I couldn’t wait to get out on my own, to be in private enterprise, to be fully responsible for my business succeeding or failing.”

The first time Buffalo Beach Resort and Campground came up for sale, Alan missed out, but when it was relisted he pounced and bought it within a day. He, his wife and two children moved to the Coromandel and took up the reins. “I had lived such a sheltered life. I was shy, but I had to talk to people every day, to look after them. I discovered I loved people.”

Alan and his daughter Alanna: modern-day magicians busily transporting Lost Spring visitors away from the world’s realities.

So far, so good. Passion yes, but madness? It was the legend of the lost spring of Taputapuatea and a family trip to Disneyland in 1985 that began the Undoing of Alan Hopping or the Making of Alan Hopping depending on which version of a good life one aspires to. The legend of the Taputapuatea stream, also known as Mother Brown Creek, captivated Alan.

The idea of hot water bubbling away beneath the dry, willow-fringed grounds of his holiday camp fed his imagination. He heard stories from locals about a Creek, which disappears underground north of Whitianga, and the legend of Mother Brown, who lived in the area 100 years ago and is supposed to have bathed her five children in the warm waters of the stream.

Then came that family visit to Disneyland. “I saw people lined up with such anticipation on their faces. They were at the door of a place that could transport them away, take them to somewhere else, just for a day.”

Alan returned to New Zealand believing he could create that same magic for people from a dry paddock of willows on his Coromandel property. He could build a hot thermal resort and call it The Lost Spring. “I was so naïve. I looked at it through the eyes of a child. I told myself that all I had to do was make it to opening day.”

Thus began the quest that cost him his marriage, nearly sent him bankrupt and drove him to physical and mental exhaustion. There were three expensive failed attempts to locate the “lost” hot spring, each costing several hundred thousand dollars. He drilled to 320 metres in 1989 and found thermal water. It was a brief moment of hope, soon dashed when an electrical failure saw the pump cables burn out, welding themselves to the drilling casing, eroding a hole in it and leaving Alan drawing nothing but rusty water and iron sand. As engineers tried to fix the casing, Alan called timeout. “It was hard, but I’d been so involved with the job by that stage I knew we were wasting our time.”

He wasn’t beaten but he was short of money. He sold his aircraft (he’d qualified for his private pilot’s license in the 1980s) and a beloved Holden V8 ute that he had bought new. “I’d put a six-inch exhaust in it to wake you up when you went around the corners. I always said I could get it back. It’s a funny thing though because, even though now I could, I’m still driving a rusted out old Holden sedan that failed its warrant. I think when you’ve sacrificed for so long it becomes hard to let yourself have those things again.” He tried again. And again. Finally, the fourth drill was successful in finding hot water 667 metres underground, 60 metres from the original well.

The water that emerges from a small crack in the bedrock is sterile, fossilized after more than 16,000 years under ground. It is rich in more than 400 minerals and surfaces at a temperature of about 48.5 degrees Celsius, with pool temperatures ranging from 30 degrees to 41 degrees. However, finding water was only the beginning of Alan’s dream. He set out to create something evoking the response he witnessed on the faces of those Disneyland guests. The magic of an escape from reality to a land of wonder and beauty. Four years, and many more millions, and his Lost Spring Thermal Spa opened in 2008. It cost him nearly $7 million.

Today The Lost Spring takes up about 1.4 hectares beneath a canopy of towering nikau trees home to tūī and kererū. Lush native and tropical planting blends around the pool edges blurring natural and man-made. In an area called The Grotto is a little piece of Alan; a pair of plastic wraparound sunglasses he dropped while concreting remain embedded in the ground. “The fellow that built this place was fearless because he believed in himself, polite but very opinionated,” says Alan.

“There is a quote by American architect Daniel Burnham: ‘Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood.’ That’s what this is all about; being inspired by others to pick up a shovel and go to work, literally. More New Zealanders need to allow themselves to be inspired by others and other cultures.

Alan rescued his 160-year-old cottage from Whitianga’s former Coghill Street sawmill and restored it from the ground up. When he moved it to the Lost Spring property in 2000, he was told the building had a fierce female presence. Alan says she has mellowed over time.”

“As a country, we play safe. I won’t call myself a Kiwi. I can’t understand why our national icon is a small flightless bird on the verge of extinction that hides away on a fabulous day and only comes out at night. I’m a proud New Zealander. New Zealanders represent all cultures and show great courage.”

“I prepared myself for success, or for success. If I found the spring and established the spa I won. If I failed to find the spring I was set free — I was a winner either outcome.”

Alanna remembers returning from a family trip to Disneyland, her dad intent on building his own mountain. “He was up on scaffolding, surrounded by chicken wire, creating moulds for what became a volcano.” The volcano (left) was the beginning of the entire Lost Spring complex. It now provides the backdrop for the pools and spa treatment rooms. “It can throw steam to nearly 20 metres but I’m yet to get it working fully,” says Alan.

“I’m not clever but I can be excited by other people. What I have done here is not amazing. I want people to take from this and do even greater things.” Alan’s daughter Alanna says her dad has been relentless in pursuing his dream. “He had this vision and he’s pretty much stuck to it all this time. The Lost Spring is his creation, his love, his passion.”

Alanna and her family, husband Jonathan and their two children Noah (9) and Annabelle (7), returned from Florida two years ago to live in Whitianga. Jonathan divides his time between captaining super-yachts and living in Whitianga, and Alanna and Alan have formed a partnership to run The Lost Spring.

Alanna says the shooting at Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High in February 2018, in which 17 students died, reinforces the wisdom of the family’s decision to relocate to New Zealand. They had lived just 30 minutes from the Florida high school.

- The fireproof race overalls were given to Alan’s grandkids Noah and Annabelle by a friend of Alan’s.

- Most of our lives is about imagery,” he says. “That’s why we have pictures of people like Bruce McLaren on the walls of the garage.

- The kids get dressed up in their gears. They get dirt up the sides of the go-karts, smashing through puddles and it makes them feel great.”

“We see the effect of the shooting on friends’ children. The kids do real drills a couple of times a year,” says Alanna. “That’s a stress you really don’t want to put on your kids.” She is also back because, deep down, it’s what she always wanted to do. Alan, who lives in an old sawmill cottage on-site, has managed the business every day for the past decade. “When your life has a narrow focus, you become an expert. You become very good at what you do because you do it every day. However, the time is near when I will seek some balance and normality,” says Alan.

“I live alone and that’s not necessarily where I wanted to be in my life, but there is something about seeing happiness in others. That’s what this place has given me, I’ve met great people.” With Alanna alongside, there are plans to redevelop the spa and treetop treatment rooms. Alan has a new project too — a go-karting track being built beside his historic cottage. “I still want something that excites me. The track does it for me.”

A fleet of five go-karts and one stock car, all rebuilt by Alan, are used by his grandchildren and their friends, and the goal is to make it to the track at Waharoa Speedway, near Matamata, before the end of summer. Alan’ wants to be the fastest. He also wants them to watch the professionals on the tracks at Hampton Downs, Waikaraka Park, Pukekohe and Baypark in Tauranga. “Many studies show how important adrenalin is to the human condition. That’s what these things are — adrenalin injectors. I’ll never forget the pure delight on my granddaughter’s face after she raced one around the track,” says Alan.

FAST TRACK

Granddaughter Annabel was five when she moved home from the States. He had her go-kart custom made. “It’s how they personalize them. It had to be pink, of course”, says Alan. “We didn’t want her feet spilling out the side so we custom-made wings to keep them in and polished aluminium pedals that she could reach. It’s that escape. Taking others to another place, inspiring them to achieve. That’s what it’s all about.”

THIS SUMMER I’LL BE…

Reading: I’ll be reading the local newspapers and NZ Life & Leisure at my mum’s house over breakfast. She has a great collection of magazines. With Alanna taking over this summer, I might have time for some reading.

Eating: Steamed Christmas pudding with cream and ice cream, sitting in the garage with my go-karts playing American rock and roll — probably, the Beach Boys. I love them.

Drinking: I’m a red wine fan, and there’s the bonus that I can believe it’s good for me. I like a good syrah. If I’m tapping into my New Zealand side, it’ll be a dark beer — Monteith’s Black. A dark beer can be very refreshing on a hot day.

Visiting: I’ll be flying to Wellington to watch the stock cars with my grandchildren and a few others. We’ll also try to get to meets in Huntly and Auckland.

INTERNAL WORKINGS

As pools are used they cool, so Alan or one of his staff visit the The Lost Spring’s central management system up to 20 times a day to make sure water is being filtered and distributed evenly to control the pools’ temperatures. There’s a precision to managing it, says Alan. “Too hot or too cold and you could end up with 100 people crowding in one pool.”

READ MORE INSPIRING STORIES

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.