8 ways to avoid storm damage to your trees

Strong winds bring down trees in forests, on farms, in parks and gardens every year and leave a big mess behind them, but there are tricks to minimise damage and save you money.

Words: Michelle Harnett

Living in New Zealand, you can count on one thing: the weather is going to change. Our skinny islands lie in the middle of an ocean and smack bang in the path of the Roaring Forties westerly winds.

Calm, sunny days can disintegrate to torrential rain and gales in hours.

John Moore leads research into tree growth and quality at Scion, the Crown research institute that focuses on forestry. He says storm force winds which bring down trees cost land owners significant sums.

“Some years the amount of wind damage in forests is minimal; some years it runs to thousands of hectares. Big blows tend to hit the country every five to 10 years, but the last couple of years have been particularly bad.”

A windstorm that tore across the Canterbury plains in September 2013 brought with it the strongest wind gusts recorded in 40 years. Forest plantations, farm woodlots, shelter belts, rural and urban gardens, and parks were flattened. Estimates of the amount of damage ran to about 1 million cubic metres of wood. A second storm followed in October.

The following April, Cyclone Ita hit the South Island’s west coast. Winds gusting up to 140 km/h felled around 20,000ha of beech and rimu forest and significantly damaged a further 200,000ha.

“The windthrow damage was the worst in generations,” says John. “The two storms are good examples of the two main types of wind events New Zealand experiences.”

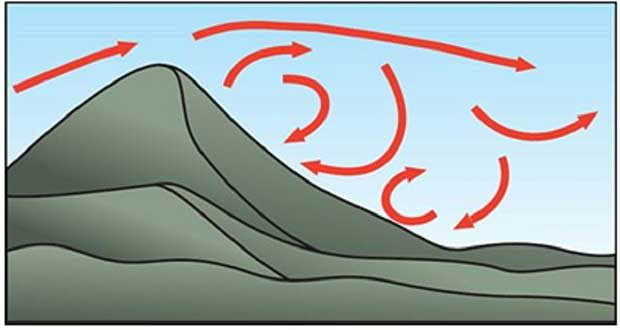

Storm-force westerlies are caused by the prevailing winds being forced over hills and mountain ranges, or funnelled through gorges, valleys and past buildings.

The Nor’west arch sometimes seen in the skies over Canterbury is a sign of wind pushing over the Southern Alps.

Then there was Ita, an ex-tropical cyclone that still packed a punch even after it had drifted south towards New Zealand.

To put it in context, the most damaging storms in the last 50 years have been the Wahine storm (Cyclone Giselle) in 1968, Cyclone Bernie in 1982, Cyclone Bola in 1988, and Ita in 2014.

“Historical records show that the whole of New Zealand is vulnerable to catastrophic winds,” says John. “The potential extent and scale of damage shows we need to think carefully about what we plant where. Luckily, there are some steps that can be taken to reduce the risk of windthrow.”

WHAT IS WINDTHROW?

John Moore.

Windthrow includes both trees that have snapped off and trees that are uprooted with their trunks intact.

“Some of the problems associated with windthrow are obvious, like the costs of clearing the fallen trees, repairing damaged infrastructure such as downed power lines, damaged personal and public property and loss of income,” says John.

Others are less obvious. Windthrow can continue to affect ecosystems long after the clean-up is finished. Dirt and debris in rivers and streams can affect water quality and wildlife. Loss of trees from hillsides can lead to soil instability and erosion and their flow-on effects. On the positive side, it is an important factor promoting succession and soil mixing.

8 WAYS TO AVOID STORM DAMAGE TO YOUR TREES

Windthrow is the result of a combination of different factors. Some we can control, others we can’t, but what we can do is take them into account when planning planting and tree maintenance.

“As foresters, farmers, lifestyle block owners and gardeners, there are three major things to take into account: where we are planting, the trees we are planting and keeping our trees healthy.”

1. PLANT IN THE BEST SPOT

The lie of the land is probably the major factor contributing to windthrow. You can’t change the land, but you can be aware of how topography affects risk and plan accordingly.

“Trees growing on lee slopes are generally more vulnerable than those on windward slopes. They often grow more quickly and become taller, and they are often not exposed to the consistent strong winds which would encourage them to adapt. When strong winds blow over a hill, gusts form on the lee side and these gusts can result in lots of damage.”

What you can do:

• protect lee slopes from damage by prevailing storm-force winds by planting on the windward slopes.

• encourage trees to grow stout rather than tall and thin by not planting too densely and controlling weeds that might compete for space and light.

2. CHOOSE THE RIGHT TREES FOR YOUR LAND

Tree choice can help and that means avoiding some of the more common trees you may see on farms.

Examples of the awesome force of the wind: a windthrown pine is snapped in two, while the example below has had its root plates torn out of the ground.

Pinus radiata (pine) is the most common plantation tree in New Zealand but it is not the most wind-resistant. Eucalypts from the ash group, or Douglas-fir, are more resistant to wind damage, although Douglas-fir should be avoided in areas where wildings are a problem.

The best trees for your block will depend on where you are in NZ and your topography.

Consulting with local tree nurseries will mean you get good advice on the best options.

3. PLANT FOR YOUR SOIL

The type of soil on your block will have a big impact on how well a tree can stay upright. Shallow soils and high water tables result in shallow rooting and increase the risk of windthrow.

“On some soils, trees can uproot and roll up the land like a carpet,” says John. “In some cases it is possible to rip the soils to break up hard pans which will help encourage deeper rooting.”

Smaller trees and shrubs are a better choice in areas with shallow soils. Native vegetation in an area is often a good guide to what survives and thrives locally.

The same planting advice applies to wet soils, which often offer reduced root anchorage.

“This is something to bear in mind when planting wet areas such as gully bottoms, stream and river edges and places where rain run-off might pool.”

4. TALL DOES NOT EQUAL GOOD

Tree height, form and the extent of the root system all affect a tree’s ability to cope with high winds, but of these factors, it’s the tree height that is probably the best predictor of vulnerability. Tall trees are simply more likely to be windthrown.

“We can work out what the critical height threshold is for different tree species by measuring the height of damaged trees,” says John.

“For radiata pine, the risk of damage is considerably higher when the trees are over 30m tall. You also wouldn’t want to thin a stand once the trees are more than 16-18m tall either.”

The height at which other tree species become more vulnerable to damage will depend on their stem form, crown shape and root anchorage strength.

Slower-growing tree species might take 100 or more years to reach the threshold height, whereas more rapidly growing species might take 20 years.

“Tree height and growth can be controlled to an extent by choosing to plant shorter or slower-growing trees. And, as with trees on lee slopes, trees should be given the space needed to grow stout rather than tall and thin in order to better resist strong winds.”

5. CHECK YOUR TREE HEALTH REGULARLY

Mushrooms sprouting from the base of a trunk, sawdust around holes made by boring insects, and misshapen, discoloured and falling leaves are signs of infections and infestations that can rob trees of robustness and resilience.

Detecting disease can be difficult at times and often the first indication is after a tree is damaged or falls in a storm.

An adult eucalypt with two leaders, making it a prime candidate for damage in high winds – pruning for one leader when young will prevent this.

“Regular tree check-ups are a must,” says John. “The likelihood of problems increases with age, so it becomes particularly important to monitor the health of large, specimen trees, such as the mature deciduous trees that shade houses, homesteads and public parks.

“In some cases it might be time to bite the bullet, remove a tree that is decayed and plant a replacement,” says John.

6. CUT DOWN THE PIONEERS

Other trees that might need removing include mature pioneer species.

These are trees that have evolved to occupy a site quickly rather than to be around for a long time and often have large spreading crowns that are more vulnerable to damage.

A rolling tree replacement program that ensures a good mix of ages and sizes avoids the possibility of many mature trees failing at the same time.

7. CHOOSE THE BEST TRUNK

Trees with a single central trunk are normally stronger than trees with two or more trunks.

The junction of two trunks is often a weak point and a strong wind could split the tree into two. This is easy to avoid by choosing trees with one leader and pruning to manage tree leaders.

“Another advantage of new trees is it is possible to shape their growth for better wind resistance and aesthetics,” says John.

8. LOOK FOR CHANGES IN THE ENVIRONMENT

Something else to be on the alert for is changes in trees’ physical environments.

Anything that changes wind patterns on a local scale can make trees more vulnerable to windthrow. For example, thinning or harvesting a forestry block can expose previously protected trees to prevailing winds

WHY NOW IS THE PERFECT TIME TO LOOK AT TREES, AND HOW IT COULD SAVE YOU MONEY

Late autumn and early winter is a good time of year to check tree health and prune them if required.

“It could be worth consulting an arborist, especially for trees growing close to houses, other property and power lines,” says John. “It’s likely to be cheaper than clearing up and repairing damage from a windthrow event.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.