Take a tour of Chris Ballantyne’s organic mini-farm in Te Atatu

A landscaper with a mini backyard farm believes small-scale food production is key to well-being and urban ecological balance.

Words: Emma Rawson Photos: Sally Tagg

When Chris Ballantyne is planting seedlings in his veggie patch or inspecting his backyard beehives, he’s focusing on the small things of garden life.

But the landscaper, founder and co-owner of Auckland landscape design company Second Nature is also thinking about the big picture while tending his garden in the west Auckland suburb of Te Atatu. As our cities become more intensely populated, Chris says green spaces will become increasingly important.

The garden borders the estuary where Chris has restored native trees at the shoreline.

“Attractive green space is essential to human well-being. There is no good reason why cities should be barren spaces dominated by concrete, glass and asphalt. A truly functioning city should be a biodiverse, sustainable ecosystem that supports humans, plants and animals – food production should be part of this,” he says.

According to the United Nations, the Earth’s population is estimated to reach 9.8 billion by 2050. To cope with human consumption, Chris believes food will eventually be produced in controlled-environment glasshouses and factories. While what we produce in our urban spaces will not feed everyone, it does add to our well-being and provides a connection to natural processes.

Brown Shaver hens peck on pests in the veggie garden.

Chris, who has been in the landscaping industry for 35 years, believes humans crave a connection to nature and this can be easily overlooked as urbanisation and technology crowd our lives.

“Gardening provides a critical connection to nature, whether it’s revegetation work, ornamental gardening or growing your own food,” he says.

Chris has created an organic mini-farm on his less-than-quarter-acre section. It produces an abundance of fruit, veggies, ornamentals, eggs from five chickens and honey from three hives, more than the family of three can consume, with excess given to friends and family. Chris likes to know where his food comes from, what goes into growing it, and he’s excited to demonstrate the potential of a suburban section.

“I want this garden to be an exemplar of what you can do with a standard urban site, in terms of how much can be produced, how beautiful it can be and how much biodiversity you can encourage.”

The backyard produces leeks, courgettes, asparagus, cherry tomatoes, butternut squash, red onions, garlic, potatoes, strawberries, cucumbers, pumpkin, carrots, silverbeet, lettuce, onions and climbing beans, the majority of which grow in raised beds. Chris cultivates potatoes and kumara in plastic buckets dug into the soil, which saves digging up the garden in search of wayward tubers.

He built the raised beds to his own modular design, with interchangeable chicken-wire nets and UV plastic to create a mini-hothouse environment.

Chris tends to the hives, which he initially established for pollination.

Chris says rigorous planning and infrastructure, such as raised beds and quality soil, will establish a garden that will endure for years.

“My lesson from landscape gardening is to get the design right from the get-go. Make the upfront investment to quickly achieve a much better result,” he says.

While the front yard is dedicated to ornamentals, the rest of the garden is dedicated to food production, with some components combining the two. Two dwarf nectarines and a peach tree (all from Waimea Nurseries) are underplanted with masses of marigolds, which creates an attractive feature that produces oodles of fruit.

Heritage potatoes grow in buckets dug into the earth next to a crop of leeks

“Dwarf varieties are fabulous for an urban setting – they produce and produce and produce. The marigolds are purely decorative, and once they’re in full flower they reflect a delightful orange glow back into the house.”

Chris irrigates the garden with rainwater from a 20,000-litre harvesting system, which tends to run dry as early as January.

“That shows how much water is needed, but rainwater is so much better for the plants,” says Chris, who follows up with town supply until the tanks are refreshed.

The garden is enriched with a compost tea blend brewed in an aerated plastic drum. The main ingredient is comfrey harvested for its nutrient-rich benefits; its tap root system draws potassium, nitrogen and phosphorus from deep in the soil. He lets the comfrey decompose before mixing it with water, apple cider vinegar, seaweed and molasses (to speed microbial action) and oxygenates it with an aquarium pump.

“Although its benefits are not scientifically proven, the health of my garden seems to be evidence that it has some effectiveness,” he says.

Working in gardens all day in a professional capacity doesn’t deter Chris from toiling over his own soil during the weekend.

“My son calls me a garden tragic, but I delight in nurturing seed, growing it to harvest and finally eating it. I know all the inputs – the food is coming directly from the garden to the plate, no transport, refrigeration, packaging or profit margins. It’s about being connected to the rich matrix of life through the soil, bees, chooks, butterflies and produce.”

CHRIS’ TIPS

1. Rotate crops to the best of your ability and if that’s not possible, refresh old soil with new. “My problematic crops, such as tomatoes and potatoes, are grown in new soil every year. If I use existing soil, I get rust or potato blight.”

2. Comfrey is an excellent multi-purpose plant: it makes good mulch, fertiliser and bee food and also deters invasive kikuyu.

3. When faced with poor soil quality, work hard to address imbalances by introducing organic matter to establish the best-quality growing environment.

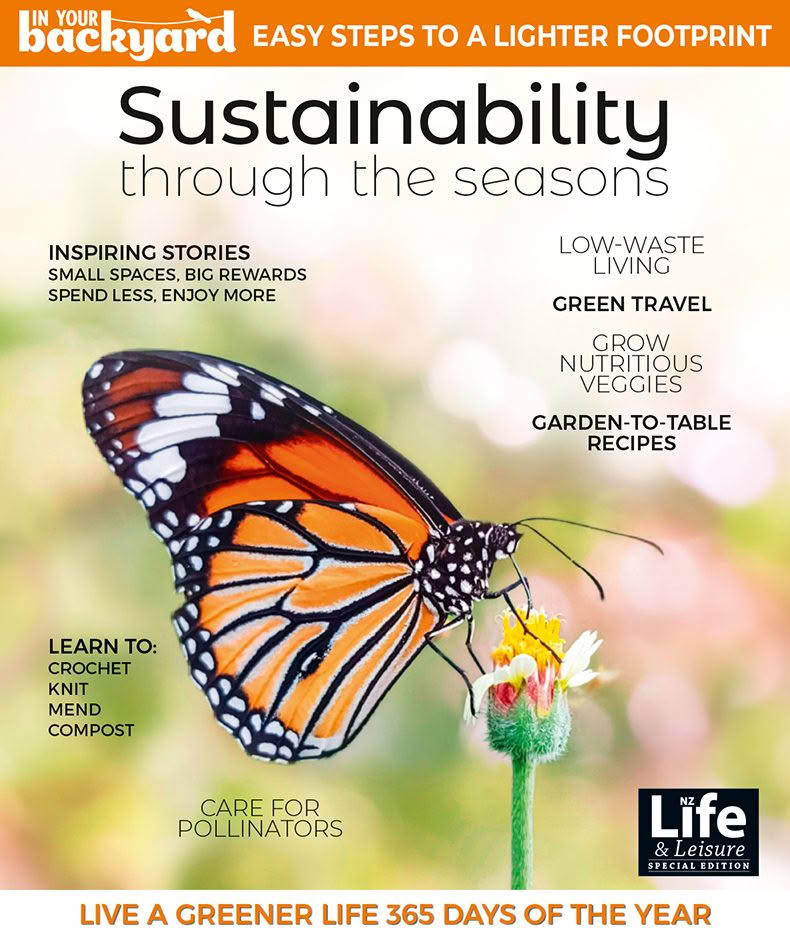

For more stories like this, read our special edition, Sustainability Through the Seasons. This special edition practical guide to living a greener and more environmentally friendly life 365 days of the year. It is packed with self-sufficiency tips on seasonal gardening, low-waste living, garden-to-table cooking, sewing and mending, bread-making and crochet and knitting.

Video: Take a tour of Rory Harding’s George Street Orchard in Dunedin

Video: How Kate Coughlan’s inner city courtyard garden became a 100% edible oasis