Pandoro founders Kaye McGarva and Richard Tollenaar’s new artistic life

The founder of a groundbreaking artisan bakery has returned to her childhood stomping ground and a creative calling that was always waiting in the wings.

Words: Ann Warnock Photographs: Florence Charvin

A deliciously fluffy chocolate mousse, whipped up in her early 20s, mapped out a large chunk of Kaye McGarva’s life. The young traveler, who was born in Hastings, had arrived across the ditch in Sydney equipped with an arts degree, an engagement with the political landscape of the 1980s (she was arrested with anti-apartheid protestors at Lancaster Park during the Springbok tour) and an op-shop wardrobe including a fluorescent-pink jersey knitted at her request by an aunt.

While doing the dishes at a Paddington café she was asked by her boss to suggest puddings for the menu. “I made her a chocolate mousse and it was fantastic because afterwards I wasn’t a dishwasher anymore – instead I was assigned to desserts and salads.”

Kaye describes her work as “playing with the shadows and hovering between abstract and representational to create a sense of the uncanny”.

Baking, chopping, frying and roasting had always been on Kaye’s radar. “There were five children in our family and my amazing mother also worked part-time at the Mayfair Hotel. Dad was a freezing worker who put in long hours. I started off making biscuits but moved onto helping with meals; it was the time of chicken chow mein. Later when I was flatting, we were very competitive about cooking nights.”

Food was also an artistic outlet. “My brothers and sister were very sporty and I was the arty one. I dreamed of being an artist and was crushed when my application for the University of Canterbury School Of Fine Arts was rejected. I lost my confidence with art for many years and instead applied my creativity to cooking.”

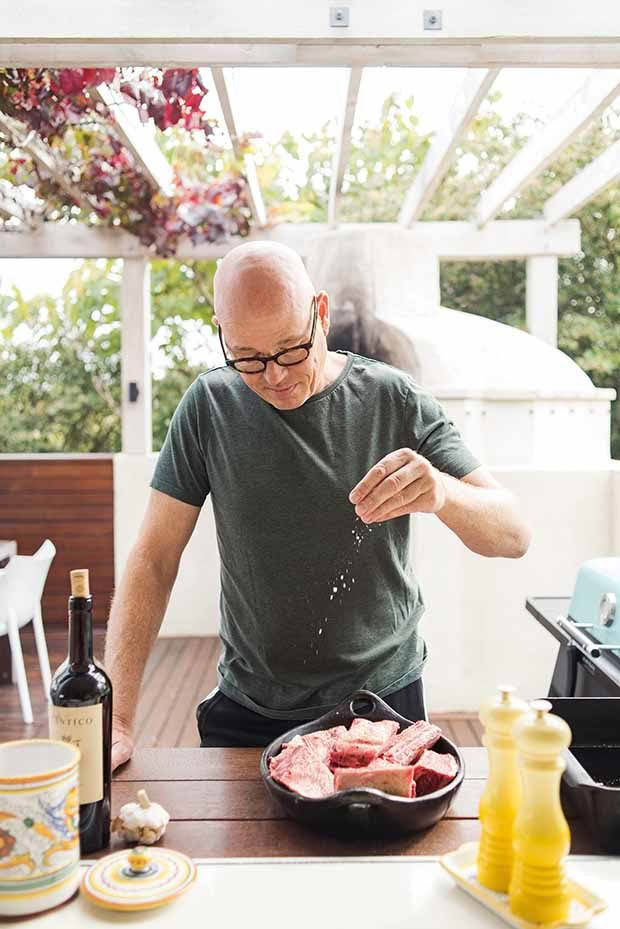

Richard seasons the evening meal. “We both love to cook and often barter over who’s going to be in the kitchen.”

Kaye’s inherent flair with food thrust her along an exhilarating culinary pathway – from dishwasher to pastry diva, and from Sydney to London where, in Belgravia, she worked alongside the yet-to-be famous Nigel Slater at the well-heeled speciality grocer Justin de Blank Provisions. Afterwards, there was a solid stint as head of pastry at Soho’s celebrated French restaurant L’Escargot, co-owned at the time by Master of Wine, Jancis Robinson. “We worked in a basement kitchen and the orders were all in French. A dumb waiter took the meals up to a brasserie on the first floor or fine dining on the second. Our ingredients were fabulous; foie gras and part-frozen baguettes were brought in from France.”

The couple relish “a homely life with family and friends, low-key dining, good wine and no television.”

London was a blast but eventually the lowly pay, frozen water pipes at her flat in a Hackney council estate and the birth of a nephew in New Zealand tipped her towards home. Back in Auckland, she headed the pastry team at Cin Cin on Quay. It was while searching the bar for a liqueur to enhance a berry gâteau she’d devised that she crossed paths with her future husband Richard Tollenaar. “I was bar manager and I said to Kaye, ‘That gâteau sounds really nice; I wouldn’t mind a slice’. I was told rather frostily that I could buy it off the menu. It wasn’t the most auspicious start,” says Richard.

The view from the pool takes in the village of Havelock North and the Kaweka Range. The couple bought the house from a cousin of architect John Scott. Scott was instrumental in its ingenious placement on the steep site and the house was designed by an architectural draughtsman in his practice.

A chilly start it may have been but the partnership between the pair warmed. Simultaneously, due to a rigorous overhaul of fringe benefit-tax rules, the nation’s restaurant scene was cooling off.

Kaye was working at Metropole where Ray McVinnie was head chef when artisan bread pioneer Tony Papas visited from Sydney to introduce the crew to focaccia and olive bread; she found it “amazing, exciting and delicious”. “Good coffee was establishing itself in New Zealand and people wanted cheaper food so bread-based meals and sandwiches were ideal.”

When Metropole was forced to close its fine-dining room because of the downturn, she hired it as a venue for a catering company. “It was a disaster – the demand wasn’t there.” Bouncing back, she turned her sights to those intriguing European breads and a groundbreaking treat – authentic fudge brownies – with a recipe sourced from an American waiter at the restaurant.

Handmade speciality breads and cakes became the backbone of Pandoro – a bakery Kaye and Richard established in a gutted dairy on Parnell Rise. It was British cookery legend Prue Leith who brought some unexpected magic to the enterprise. In New Zealand for a symposium of food writers, she announced she’d visited Pandoro and found its Italian breads to be the best outside Italy.

Using a sourdough starter from Pandoro days, Richard regularly bakes loaves in the outdoor oven which is also used for slow-cooked family favourites – corned beef, lamb shanks and beef cheeks.

“We just exploded. We’d worked in restaurants not bakeries so we only used old recipes, pure ingredients and were driven by flavour. On one occasion a flour company sales rep asked what improvers we used in our bread. I had no idea what he meant.”

Success was instant. “They were long days and it was hard work with 3am starts but we were young and naïve which helped. My brother Neil joined us and food writer Lauraine Jacobs encouraged Richard to study sourdough bread making in California. I loved what we were doing – the pace, the intensity. We constantly sold out.”

The 70s cane furniture in the couple’s cosy sitting room was inherited from Richard’s grandparents who lived in Singapore.

Pandoro rode the wave but, out of the blue, Kaye faced a personal knockback. On the day her daughter Olivia turned two, she discovered a lump in her breast. A mastectomy, six months of chemotherapy and recovery followed. “Such an experience can be helpful to your view of the world. I think you must confront your vulnerability and it’s easy to feel scared about a recurrence but it’s important to get on with the business of life,” she says.

- The couple enhanced the house and courtyard with “a serious, sympathetic revamp” focused on maximizing spaciousness and the view.

- Furniture, including a mid-century dining table made in New Zealand, salutes the home’s 60s heritage.

- The jacaranda tree adjacent to the front door has glorious early summer blossoms.

- Kaye’s childhood home was “the wrong way round for the sun”. When she first walked into their Havelock North house in 2005 it was a revelation of light, space and strong design.

- “I was so struck by the feeling – you can see right through the house from one side to the other and the fantastic view beyond.”

Richard says Kaye’s health scare reinforced the importance of walking towards challenges. “On tough days when Kaye was wiped out I thought, ‘Okay I’m a solo dad but we need to keep putting one foot in front of the other because the sun will still come up, Olivia and Zoe need to get dressed and we mustn’t get bogged down.’”

Several years after Kaye’s cancer, a buyer for the business – by now a chain of artisan bakeries in Auckland and Wellington with 150 staff – appeared on the scene. The opportunity to exit Pandoro coincided with the couple’s desire for a change of gear.

The couple love the 60s summit stone wall in the sitting room.

The day the deal went unconditional there was devastating news: Kaye’s younger brother Steven, 39, died in a car crash, killed by a drunk driver while driving home from Palmerston North to Hastings.

Regular visits to Hawke’s Bay ensued and, without the dominating force of Pandoro in their daily lives, new possibilities surfaced. Kaye embarked on painting classes propelled by a renewed energy to return to art. The pull to her childhood stomping ground strengthened – the couple wanted to be closer to Kaye’s family, were weary of Auckland traffic and Richard had a long-harboured dream to grow grapes and make wine.

The blue artwork above Richard’s collection of vintage cameras is Blue Sphere #186FD8 2017 by Auckland abstract photographer Fraser Chatham while the sculptural work is by Sue Mabin; both artists are represented by Muse.

Those desires manifested themselves in 2005 when the couple bought a 1960s dwelling on the side of Te Mata Peak above Havelock North. A gentler rhythm of life took hold. Much to the amusement of their then high school-aged daughters (now 22 and 21), Kaye and Richard got out their own school bags. Richard ticked off a Diploma in Grapegrowing and Winemaking at the Eastern Institute of Technology in 2013 and planted a micro vineyard of chenin-blanc grapes on the slopes beyond the house while Kaye captured that illusive dream with a Bachelor of Visual Arts and Design a year later.

Kaye lost two diamond studs among the grapevines adjacent to the house – so Richard named his vineyard Lost Diamond Wines.

Amidst the realisation of ambitions there has also been heart-breaking pain. Three years ago Kaye’s beloved older sister Pam was also killed in a car accident. “It was my second sibling to die in a car accident through no fault of their own other than being in the wrong place at the wrong time. I don’t properly understand grief but it’s so important to keep talking about those we’ve lost. I have a strong faith in humanity. I had my fortune told on a street in Los Angeles by a woman who said to me, ‘Go in search of life; don’t merely go with the flow’ and that prompted me to study art.”

In early 2017, art moved centre-stage in Kaye’s life with the opening of her contemporary gallery, Muse (museart.nz), in Havelock North. At Muse she has a clear agenda: breaking down elitism and coaxing the community through the door. Her own artistic practice – which focuses on illusion and perception and is informed by the works of American ‘light and space’ artist James Turrell and British optical-illusion art exponent Bridget Riley – is an ongoing joy.

The piano in the sitting room is a Brodmann. The couple’s daughter Olivia, now majoring in music at Victoria University, learned to play on it; their other daughter Zoe is a graphic designer and designed the brand identity for their art gallery, Muse.

She now divides her time between her studio at Waiohiki Arts Village near Taradale and the gallery. Richard does the gallery bookkeeping – “it’s like herding cats” – and suspects his Muse involvement will be similar to Pandoro: “I’ll end up being drawn in. It’ll become full noise and a big part of my life.”

He says there are learnings to share between the businesses of bakery and gallery. For Kaye it is the wisdom from her late mother Vivian that continues to resonate. “Mum encouraged me not to put my art aside. She grew up in wartime London, was evacuated several times and her own education and opportunities were cut short but she always buoyed us along.”

Art is the highest form of hope’– the sentiment expressed by German visual artist Gerhard Richter is Kaye’s most-loved quote. Her studio at Waiohiki Arts Village is a place of “optimism and happiness”. The two works behind her are Copper Creases 2015 and Serenity Now 2017.

Kaye says the opening of the art gallery has brought with it a sense of having come full circle. From wafer-thin pastry and profiteroles to ciabatta and focaccia, food and its execution fed her soul for 30 years. Now that kitchen creativity is transposed to the canvas and art gallery.

“I remember Richard once gave me an easel but at the time I felt I had nothing to say.” Now there is so much to be said.

DO’S AND DON’TS OF BUYING ART

Art is much easier to buy than sell so take your time, do your research, and look for authenticity. Know the difference between art and decor. Don’t choose art because it matches the curtains.

Be mindful of provenance: buying a painting made in a sweatshop in Asia doesn’t equate to buying art. Expect your taste to change over time. You may find the most difficult-to-like works are ones you end up loving.The decision to buy art should be based more on emotion than investment potential.

BEST TIPS FOR BUYING ART ON A BUDGET

Emerging artists are often very good value. Go to end-of-year tertiary graduate shows where the prices are affordable, the money goes directly to the student and you have the satisfaction of helping someone start their career.

Art auctions can be great places to get a bargain but do your research first.

At art fairs there tends to be plenty of well-priced art, but they can be overwhelming. Don’t give in to a fear of missing out: if you don’t secure the work on show, chances are the artist can do another one. Get their card.

READ MORE: RICHARD’S TIPS FOR MAKING THE PERFECT SOURDOUGH