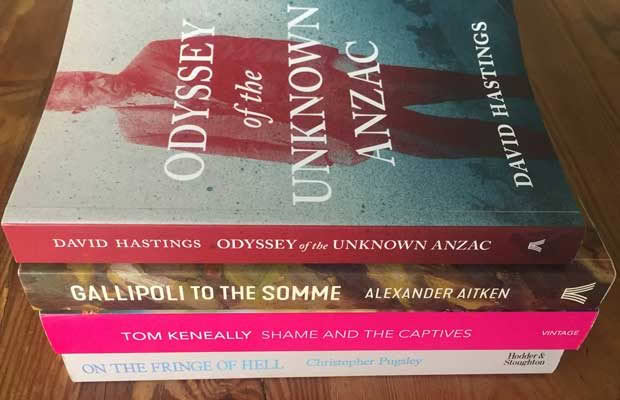

ANZAC book reviews: Odyssey of the Unknown Anzac, Gallipoli to the Somme, Shame and the Captives, Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story

Rosemarie White reviews four very different New Zealand accounts of wartime campaigns.

Reviews Rosemarie White

Odyssey of the Unknown Anzac

by David Hastings

(Auckland University Press)

Christmas Day 1918 must have been a very sombre affair. Since 1914, 10 per cent of all New Zealanders had left to serve overseas and about 18,500 had been killed. Just when the war was finally over the influenza epidemic struck, killing about 8000 civilians in two months, mostly fit, healthy people in the prime of life. It was a terrible end to a terrible war.

But the suffering didn’t stop when the guns fell silent; the men who came home were enduring the psychological effects of a mechanized killing that had never been seen before. “Sights I wish never to see again, the less said the better” wrote one wounded soldier on his way home.

The Somme Offensive became known for the epidemic of the condition known as shell shock. The term covered both the physical consequences of long periods of sudden, violent concussion from the guns (and sometimes being buried by exploding shells) but was also used to describe the strange symptoms shown by men exhibiting psychological effects of trench warfare. Soldiers wandered from the battles, dazed and confused, and risked being declared deserters. Deserters in the New Zealand Division were shot.

Many corpses were not able to be identified and many families did not know how their men had died, where they lay or, if indeed they were really dead. Cruel rumours that the Germans were holding hundreds of thousands of Allied prisoners in secret camps swept around, making families vulnerable to swindlers and scammers in Germany who played on their grief by promising information for money.

In 1928 the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia printed 100,000 leaflets asking for help identifying an unknown patient in a Sydney mental hospital, ‘a supposed Australian or New Zealand Soldier, found wandering the streets of London in 1916 or 1917’. Within days scores of people contacted the League and eventually he was named as George McQuay from Stratford, New Zealand. Reunited with his family, he returned to Stratford and disappeared from public view.

David Hastings has written a compelling story which follows George McQuay’s journey from rural New Zealand through Gallipoli and the Western Front.

Gallipoli to the Somme: Recollections of a New Zealand Infantryman

by Alexander Aitken

(Auckland University Press) was originally published in 1963 and has been reprinted for the WW1 centennial.

Aitken – possibly a true polymath – was a mathematical genius who could multiply nine digit numbers in his head. He took a violin with him to Gallipoli and practised Bach on the Western Front. He knew the epic poems The Aeneid and Paradise Lost by heart. His memory was dazzling.

Aitken was wounded in 1917 and started writing his memoir in Dunedin Hospital. The book was recognized as a literary memoir of the Great War to rival poets Sassoon and Graves and Aitken was elected fellow of the Royal Society of Literature on the strength of this work. After the war he studied in Scotland and became the Chair of Mathematics at Edinburgh University, a post he held for 19 years.

No matter how familiar you are with the tragic story, it’s impossible to read this account Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story by Christopher Pugsley without being moved and troubled. And if you are strong enough to read further, Chris Pugsley’s later book On the Fringe of Hell, New Zealanders and Military Discipline in the First World War (Hodder & Stoughton) is a sobering and detailed picture of how the New Zealand Division maintained its high standard in the appalling conditions of trench warfare on the Western Front.

Shame and the Captives

by Thomas Keneally (Vintage)

Just outside the Wairarapa town of Featherston, a memorial garden marks the site of a WW2 riot in which 48 Japanese prisoners of war and one guard were killed.

The camp held 800 Japanese prisoners of war, captured in the South Pacific. On 25 February 1943, a group of recently arrived prisoners staged a sit-down strike, refusing to work. Guards fired a warning shot which may have injured a prisoner. The prisoners then rose up and the guards opened fire. Wartime censors kept details of the tragedy quiet for fear of Japanese reprisals against Allied prisoners of war.

Keneally’s book is a fictionalised account of the Cowra Camp outbreak in New South Wales in 1944 and the details are remarkably close to the events that actually took place in the Featherston camp a year earlier. Keneally recreates the cultures and motives on both sides of this calamity. Another compelling story from the master Australian author of Schindler’s Ark.