Waikato vet Danielle Hawkins draws on country life for popular romance novels

The family (from left) Jarrod Hawkins, Blair Hawkins, 7, Danielle Hawkins, Katherine Hawkins, 9, and Evan and Liz Cowan, has nurtured this land for four generations, protecting and regenerating areas of native bush.

An Otorohanga vet has won an international following writing romance novels with a country twist.

Words: Venetia Sherson Photographs: Tessa Chrisp

In one of Danielle Hawkins’ romantic novels, the main character, Jo, bolts from the city to a small rural town after her boyfriend cheats on her with her best friend. In another, a young country vet juggles courtship with the calving season.

So, it’s no surprise to find the author sitting cross-legged in an armchair, with views of some of the King Country’s best dry stock, talking up the pleasures of bucolic life.

Her stories, she says, show that people are the same no matter where they live.

The view to Mt Pirongia from the homestead, Kamahi.

“Many chick-lit books are set in cities. The characters work for glossy magazines. But you are not a hick when you live in the country. You don’t sit on a porch with a shotgun between your knees.”

That’s not to say she couldn’t kill a rabbit if she had to. Or put down a dying cow. As a farmer and vet as well as a writer, she’s called on to do both. It is this blend of roles, plus a four-generation connection to place, that provides such rich pickings for her books.

“I remember as a child feeling smug and pitying city kids,” she says. “One who stayed with us asked if he could take his shoes off to run around outside.”

Danielle says she became a vet because, as a child, she loved the books of Yorkshire vet-turned-writer, James Herriot.

The road to the house named ‘Kamahi’ is steep and winding. It’s 15km east of the bright lights of Otorohanga (population 2740) most renowned for its Kiwi House and proximity to the Waitomo Caves.

Before the road was tar-sealed, the school bus had to turn back before it got to the top, which gives a sense of the gradient. But the view is worth it. To the west are the mauve slopes of distant Mt Pirongia; everywhere in between is rich with dark green patches of native bush.

‘You are not a hick when you live in the country. You don’t sit on a porch with a shotgun between your knees’

Danielle grew up at Kamahi and went to Otewa School, a short hop down the hill where her great aunt was a teacher and passed on her “old-school” love of nouns and verbs. It was here that Danielle wrote her first “book” about a pet lamb, entitled The Life of Pin.

Danielle writes at the kitchen table when the children are at school, and when she’s not working as a vet.

She says she was always a bookworm, encouraged by her mother Liz Cowan, who studied English and German literature at Waikato University, and her father, Evan, who read her stories and poetry at bedtime.

But she didn’t enjoy the concept of ‘literature’ as defined at secondary school.

“It was so pretentious. I don’t like being told things are ‘fabulous’.”

Katherine would love a pony of her own, but that’s still on the “to-be-considered” list.

He became a vet, possibly encouraged by her father’s interest in science (he’s a chemistry and physics graduate), but more probably because she was a fan of Yorkshire vet-turned-writer James Herriot. Danielle’s first practice was at Mangawhai, where she met her husband Jarrod.

Unlike in her books, where eyes often meet across a crowded room and cymbals crash, it was not love at first sight. “He was working on a dairy farm, had long red hair and a bogan Megadeath T-shirt.”

Jarrod, Blair and Katherine cherish the magnificence of the bush they have inherited and understand the need to protect and nurture native birds.

But, like a well-developed plot, love blossomed over time. The couple came to the Waikato, where they expected to start saving for a dairy farm of their own.

“Then mum and dad asked if we’d like to lease their farm.” She says they didn’t hesitate although, “Jarrod had to quickly buy a manual on dry-stock farming.”

Returning to one’s roots is often fraught. People and places change. Sweet childhood memories may not equate to adult pleasures.

But what Danielle discovered was that the farm where she was raised was indeed her special place.

Grandson, Blair, has learned to appreciate the pleasure of growing veggies, as well as planting trees.

“I felt I’d won the lottery getting to live there again,” she says. Her love for the land was initially passed on by her grandfather, Arthur Cowan, one of New Zealand’s most prominent conservationists, who grew up on the dairy farm next door.

When he returned from World War II, where he served time in two POW camps, he set out to create a legacy of native forest restoration.

The work continued when Evan, Arthur’s eldest son, and daughter-in-law Liz, took over the property in the late 1970s.

Three generations now live on the land Arthur developed: Evan and Liz in the home they built in 1981; Danielle and Jarrod just up the road with their children, Katherine, 9, and Blair, 7.

- Kamahi Cottage, New Zealand’s only five-star farmstay, is run by Liz.

- The family often gather for meals on the front lawn.

- Liz, who was born in Switzerland, loves preparing food for guests.

- Liz loves showing guests the beauty of the King Country.

- Evan Cowan taught himself to play the bagpipes. They can often be heard at sunset echoing across the valley.

When their great-grandparents were alive, there were four generations within a tui call. Jarrod has taken up the mantle of conservationist and continues to add to and maintain the property which includes more than 100 hectares of protected native bush, fenced off in 1970s.

He monitors around 450 bait stations and possum trap-lines. Last year tomtits were spotted on the farm for the first time since 1947.

Danielle says she always loved popping over to see her grandparents when they were alive, and being part of huge gatherings of cousins, aunts and uncles at Kamahi. There is comfort in that closeness.

Danielle draws inspiration for her books from her experiences living in the country and working as a rural vet.

When she was diagnosed with breast cancer in January last year, her world tipped on its axis. During treatment, she was too sick to write. Ironically, a character in one of her books had breast cancer. “If I knew what I know now, I could have written it much better,” she says wryly.

She is now well and working again; she writes three days a week and then goes off to tend sick animals.

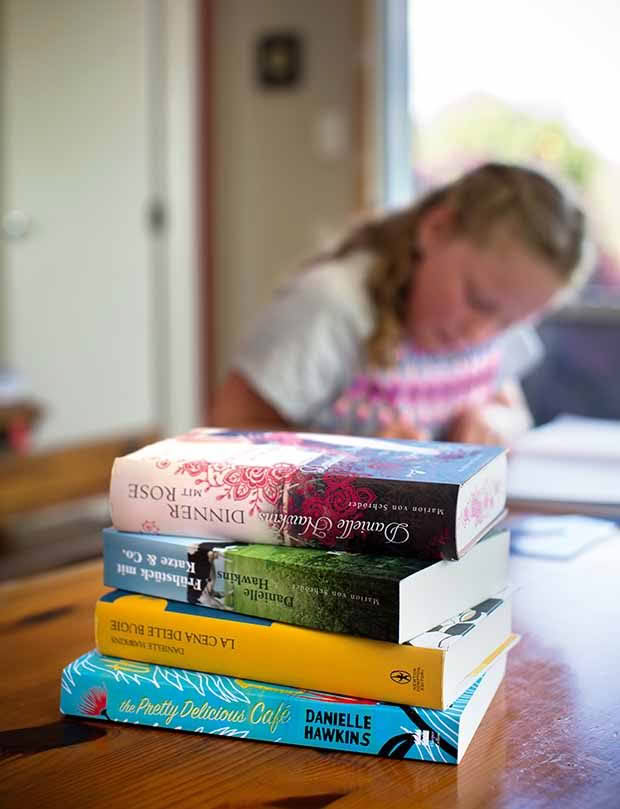

She began to write in the romantic fiction genre after her first book – about a dystopian New Zealand – was rejected. The publishers didn’t like the plot, but they praised her writing. They also added, “There’s a market for rural romance.”

So that is what she wrote. Dinner at Rose’s was completed when she was pregnant with Blair.

Since then there have been two other books – Chocolate Cake for Breakfast, about a vet who falls for a well-known rugby player, and The Pretty Delicious Café, where two women work in a restored café.

Danielle writes at the kitchen table when the children are at school, and when she’s not working as a vet.

And she’s hitting the mark both here and abroad. Reviewers have described her books as a cross between the television series Doc Martin, about a socially-inept but lovable British GP, and the works of James Herriot, whom she aspired to be as a teenager.

Readers like that she deals with everyday issues and makes them laugh. Her parents are enthusiastic fans (Liz can identify with the characters) and Evan has her books downloaded on his e-reader. “She has a wonderful grasp of Kiwi dialogue,” he says.

Danielle has just completed her fourth book about a woman whose life is a lot like hers.

The family is passionate about conservation and trapping predators and today Jarrod carries on the work of Arthur Cowan and his wife, Pat.

There’s a family sheep farm, small children to care for, and a part-time job. “The difference is that she, poor sausage, married an idiot.”

In conservation terms, Arthur Cowan was the equivalent of a tall totara. During his long life – he died aged 98 – he planted hundreds of thousands of trees and flaxes, which now garnish the King Country.

He often spotted ideal planting spots while driving and would return with spades and a band of helpers to dig holes and bed-in the young plants.

But his influence went far beyond his own province. In the 1970s, he helped save the kiwi on land being developed in Northland. Every Friday night he would head up the motorway in a convoy with others to trap the birds and release them in safe areas.

His son, Evan, says his father had a huge love for his home patch, and often wrote home about it when he was a prison of war.

“The land on which you have grown up – and walked every square foot of – is different from a piece of land you buy,” he says.

Arthur’s passion was shared by his wife Pat. They passed this on to their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren over more than six decades.

In 1988, Arthur was awarded the Loder Cup for his services to conservation, and in 1993, an MBE.

But the lasting monuments to his work are dozens of protected forest reserves, including the 466ha Ed Hillary Hope Reserve on the Hamilton-to-Raglan road, completed just weeks before his death.

A LEGACY OF TREES

In conservation terms, Arthur Cowan was the equivalent of a tall totara. During his long life – he died aged 98 – he planted hundreds of thousands of trees and flaxes, which now garnish the King Country. He often spotted ideal planting spots while driving and would return with spades and a band of helpers to dig holes and bed-in the young plants. But his influence went far beyond his own province.

In the 1970s, he helped save the kiwi on land being developed in Northland. Every Friday night he would head up the motorway in a convoy with others to trap the birds and release them in safe areas. His son, Evan, says his father had a huge love for his home patch, and often wrote home about it when he was a prisoner of war.

“The land on which you have grown up – and walked every square foot of – is different from a piece of land you buy,” he says. Arthur’s passion was shared by his wife Pat. They passed this on to their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren over more than six decades.

In 1988, Arthur was awarded the Loder Cup for his services to conservation, and in 1993, an MBE. But the lasting monuments to his work are dozens of protected forest reserves, including the 466ha Ed Hillary Hope Reserve on the Hamilton-to-Raglan road, completed just weeks before his death.

DANIELLE’S SURVIVAL TIPS

While she does not claim to be superwoman, Danielle knows how to wrench order from the jaws of chaos…

Do not – I repeat DO NOT – spend just five minutes checking Facebook before you start your ‘to do’ list. Nobody spends five minutes on Facebook. You’ll waste an hour, and then you’ll feel bad about it.

Tell yourself you only have to work for 10 minutes. That you only have to vacuum the living room, or weed that little patch of garden, or write a hundred words. Usually it’s quite fun once you start, so you do more than you were going to, and even if not, at least you’ve accomplished something.

It is possible to work full-time, cook lovely meals, have a tidy house, grow all your own vegetables, take the children to five after-school activities each, run 20km a week, start every day with a kale smoothie and have beautiful fingernails. For about a week. And then you’ll have a nervous breakdown. Don’t be so hard on yourself. To hear more from Danielle, visit her Facebook.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.