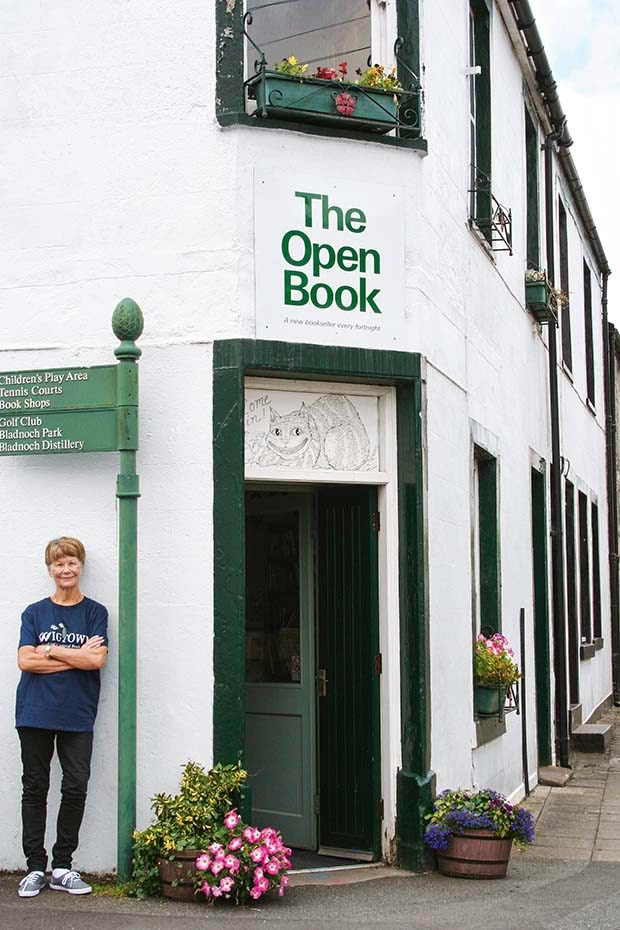

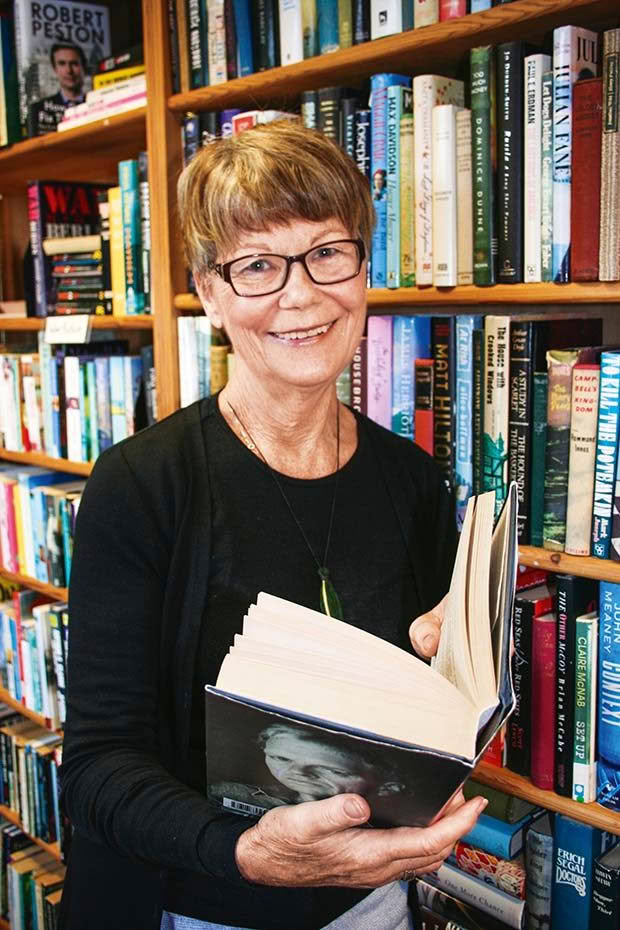

Kiwi journalist Venetia Sherson works in The Open Book in Wigtown, Scotland

A New Zealand bibliophile discovers the pleasures and pitfalls of running a bookshop in a small Scottish town.

Words and Photos: Venetia Sherson

This article was first published in the November/December 2017 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

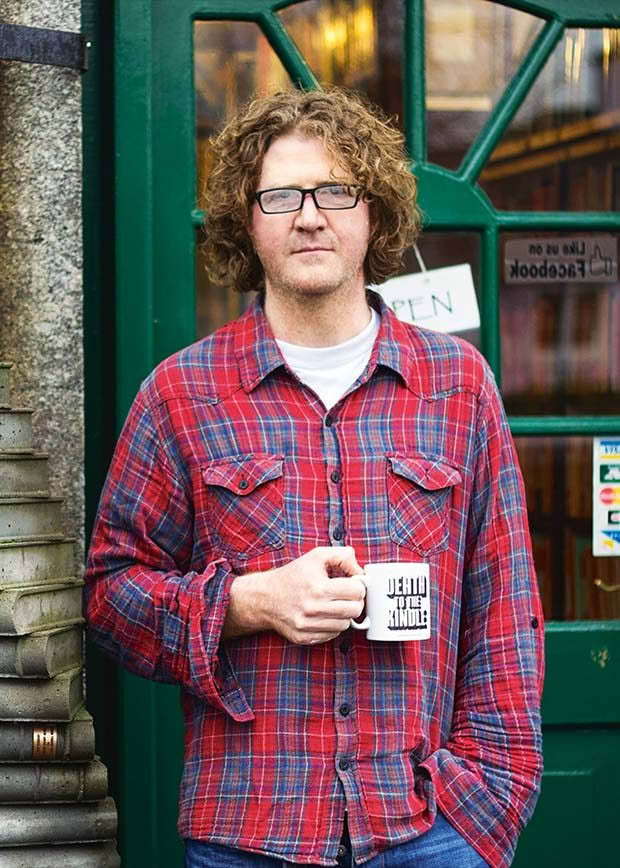

“What would you say if I told you I was carrying a Kindle in my case?” I ask Shaun Bythell, a man who looks uncannily like British celebrity chef Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall on a bad-hair day. It’s a dangerous question to ask in the small Scottish town of Wigtown, which owes its life to books. And one where – in earlier times – stroppy women were tied to the stake and drowned on an incoming tide at the mouth of the River Bladnoch.

We are drinking wine in the kitchen above Shaun’s bookshop, where 100,000 titles – some first editions – are carefully arranged over a mile of shelves in his grade II listed Georgian building. In a town of bibliophiles, Shaun Bythell is the book king. He is also known not to suffer fools.

Shaun Bythell doesn’t suffer rude customers – or Kindles – gladly.

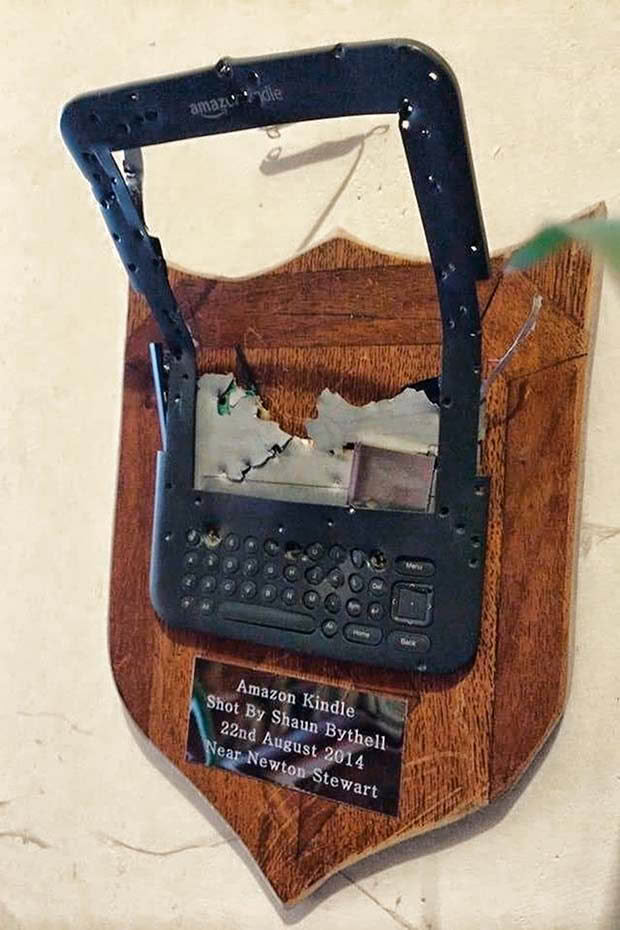

“Well,” he says, “I wouldn’t kill you.” Then he asks, “Have you seen the trophy in the entrance way?” I have. It is a Kindle, hung like a game hunter’s kill, riddled with bullets from a 12-bore rifle. The brass plaque below reads, “Amazon Kindle. Shot by Shaun Bythell, 22 August, 2014, near Newton Stewart.”

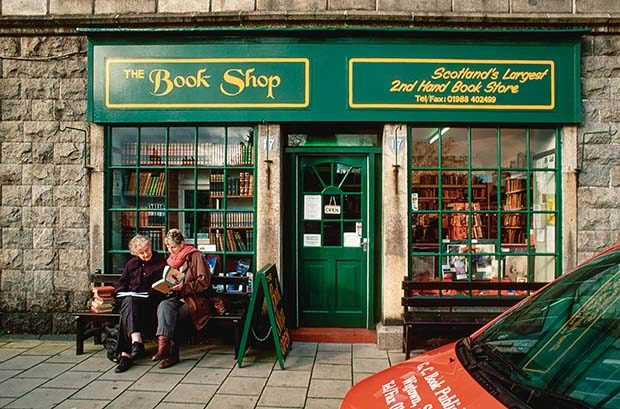

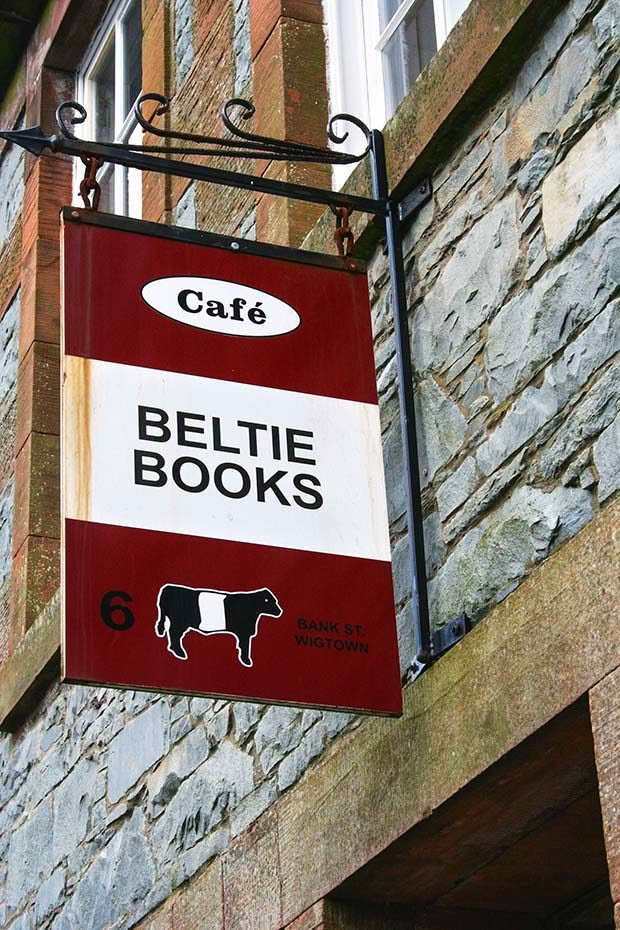

Wigtown is Scotland’s National Book Town. It has approximately 900 residents and a dozen, mostly second-hand, bookshops: one for every 75 citizens. “A town isn’t a town without a bookstore,” wrote Neil Gaiman in American Gods. In Wigtown, every second shop sells books. They have names like Reading Lasses, Curly Tales, and Beltie Books (named after the black cattle with white cummerbunds that graze in the region). Shaun’s place is named The Book Shop. It is the largest second-hand book store in Scotland, and the one to which book-lovers gravitate from all parts of the globe.

I have come to Wigtown to run a bookshop for a week, a privilege for which I have paid 150 pounds. This entitles me to an upstairs flat and the keys to The Open Book downstairs – a shop the size of an average living room. The rules are simple: open and close whenever you like, display whichever books take your fancy, price them according to similar books in stock, and get to know the locals.

One local greets me on arrival. Tall, tweedy and charming, George Moore is used to meeting greenhorns who love books but know nothing about selling them. “It’s quite simple,” he says. “There’s a ledger to write down the type of books sold; we only take cash and the cash box is labeled to make it easy to give change.” The last time I sold anything was in an Italian food market, where change was randomly hurled into a tub slicked with salami fat, so this should be a breeze. As he leaves, he adds: “The minister’s wife will probably drop by to give you a hug. And you may get a delivery of shortbread from Nannette. She usually makes it for new guests.”

The first customer arrives before he disappears. She’s looking for A Tale of Two Cities. I’m tempted to say, “Where the Dickens could it be?” But she has a serious look. We don’t have it, although she reports we do have Our Mutual Friend and Hard Times. I manage a rapid circuit of the shelves reading labels. There’s a large crime section, stacks of books on ornithology and four shelves on railways.

Shaun Bythell says you can spot the rail enthusiasts. “Always men, always bearded, knowledgeable and never rude,” he says. “They have an absolute passion for what has been lost.” Customer Terry is typical. He’s after books about commemorative railway stamps that feature in Australian history. He once bought a stamp for 10 pence and sold it for a price that bought him a car. He mourns the slow death of trains for passenger transport. “Do you know you can’t catch a train in north Tasmania now,” he says. I did not.

The greatest pleasure of bookselling – apart from being surrounded by books – is the knowledge acquired during transactions. On day one, I learn from fly fisherman Graeme that high rainfall keeps sharks away. “Sharks like salty water. That’s why they head for Australia and New Zealand.” Another fisherman, Ed, gives me a lesson on hermaphroditic fish. Sally, an English teacher from Edinburgh, says Polish parents are the only ones who read to their kids. “Parents are so caught up in their own worlds.” Steve, a local ambulance driver, who is a volunteer at the Wigtown Parish Church, tells me tests on a hidden stone in the church wall revealed it was 1000 years old.

Wigtown was facing a slow death in 1998 when it was anointed Scotland’s National Book Town.

The place had always appealed to nature-lovers, attracted by the salt marshes of Wigtown Bay and the surrounding Galloway hills dotted with Neolithic burial cairns and tumbled castles. But in 1997, the population was 800 – 200 less than two centuries before. The major employers – a whisky distillery and a creamery – had closed; the magnificent Victorian municipal building was derelict. Young people left to find work or study. Strangely, the decay worked in the town’s favour. The criteria to win a National Book Town title included aims of regeneration, economic benefit, plus enough empty buildings to house new businesses. With its new title, Wigtown’s fortunes changed. In one year, a million pounds of property changed hands. Bookshops opened. New residents moved in.

Jessica Fox fell in love with Wigtown – and with a bookseller.

One of those attracted to the town was then 25-year-old Jessica Fox, a NASA employee living in Los Angeles. Over-worked, rarely dated and with little time to socialize, she had a dream about a bookshop by the sea in Scotland. She typed “used bookshop Scotland” into Google and Wigtown came up. She contacted Shaun, who offered her board and lodging in return for work. Neither guessed it would also lead to an eight-year love affair, about which she has written a book (Three Things You Need to Know About Rockets).

It was Jessica’s idea to set up The Open Book. She figured more people would enjoy an experience of running a bookshop. Plus, she wanted people from around the world to visit and celebrate books at a time when hundreds of independent bookshops were closing. In the three years The Open Book has been running, 140 tenants have taken up the challenge. The waiting list is now three years.

Back in the shop, I am having fun with a Blind Book Date, which is like a lucky dip. The idea is to wrap a title in brown paper and write a teaser on the front. The books cost one pound. A young lad sweeps through the door, wearing fur and leather, lured by a quote I have written on the blackboard: “The world is a book, and those who don’t travel, read only one page.” (St Augustine). He unwraps his pound purchase, which is Nelson Mandela’s Walk to Freedom. “Cool,” he says. “One of my heroes.” Craig, from Yorkshire, wearing a paint-encrusted T-shirt chooses A Guide to Good Grannies. “Excellent choice,” he says, and seems genuine. “I’ll give it to my wife.”

At the end of the week, I have sold 42 books. The profits wouldn’t feed a family, given that most are priced below five pounds. But it has given me a taste of book selling and the people who read books. “It’s not a quiet life,” Shaun Bythell had warned me. “You won’t sit around smoking a pipe.” He doesn’t especially enjoy customers, who can sometimes be rude, and about which, he has written a book, Diary of a Bookseller. He prefers to forage for treasured titles in the libraries of castles and estates. At a castle in Ayrshire, among 3000 books, he found a copy of The Temple of Flora, by 18th-century artist Robert John Thornton. “If I could have kept it, I would have done. It took my breath away.” It sold for nearly $10,000. He also found 10 Ian Fleming “firsts”, still in their dust jackets.

A Brass plaque in The Bookshop features a deceased kindle.

The most expensive book I discover in my shop is Reminiscences of an Octogenarian Highlander, by D Campbell, priced at 50 pounds. But the experience has been worth far more. Wigtown has shown that small towns with big ideas and big hearts can thrive. As I close shop, I discover a small package on the stairs: Nannette’s shortbread.

IT’S AMAZING WHO YOU MEET IN A SMALL SCOTTISH VILLAGE

“You must meet my partner,” says Andrew Wilson, who owns Beltie Books, a bookshop and eatery that looks out over a splendid garden. “He’s a Kiwi.” A man arrives, disturbed from a shower. “Hello, I’m Nick, Karen Walker’s brother.”

There is a striking resemblance to his famous fashion designer sibling. But most people in this town wouldn’t know that. In Wigtown, which she has visited several times, Karen Walker is simply known as Nick’s sister.

Nick is a psychiatrist. He and Andrew have been together 26 years. They met when Nick was traveling in Scotland, and Andrew was catering at a pub in Dumfries. Wigtown is Andrew’s turf, the place near where he grew up and where his mother lived nearby until recently. In 2010, when the position of a psychiatrist came up in Wigtownshire, the couple had been working in Glasgow and Aberdeen. They thought, why not?

They bought the place next to the bookshop they now own, and used it as a holiday let until they were ready to move. Then they bought the current building, where Andrew makes excellent coffee, feather-light shortbread and stocks books about Scottish history. Nick helps when he’s not seeing patients.

Nick says he still feels half-Kiwi and the duo may consider living in New Zealand at some stage. “But Andrew’s pretty hefted [an old English word meaning attached] to Scotland.” They say Wigtown is small, but it attracts artists and creative people. “Karen loves it here. But she feels the cold. Last time she visited, it was quite a warm spring day, but she sat outside drinking soup, still wrapped in cashmere.”

VENETIA’S SEVEN TRAVEL TIPS

1. Read the travel pages and stories about places of interest. I have already diaried the Italian town of Bormida, which is luring new residents with rock-bottom real estate prices. I also want to visit places with strange museums; for example, the Museum of Broken Relationships in Zagreb and the Museum of Failures in Sweden.

2. Follow your interests and your instincts. I’m a story-teller, so I am motivated by places that will deliver stories. A lifelong love of horses took me to a remote farm on the Central Plateau, where I rode Kaimanawa stallions; as a vegan, I want to visit Turin, where the mayor wants residents to give up meat. There are 30 meat-free eateries.

3. Define yourself differently. Be adventurous. You don’t need to jump off cliffs or sleep with snakes. But think beyond a deck chair. Be childlike. What did you enjoy doing before routine and responsibilities took over? Act on your passions.

4. Consider staying in smaller towns – for longer. This is good for you and good for the planet. Many small towns struggle to attract tourists, yet the experience of staying in a village can be richly rewarding and cheaper.

5. Travel with positivity. I always travel with optimism. If things go wrong, I deal with them. Trepidation is an unhappy travel companion.

6. Consider volunteer work abroad. It’s a cheap way to travel, and age is generally no barrier. The oldest wwoof-er on the Italian books is in her 80s. It’s a great way to meet people with shared values – and to get fit.

7. Don’t act your age. It’s easy to say, “I couldn’t do that.” You won’t know until you try.

WHY I TRAVEL DIFFERENTLY

In another life, I would have been a bookseller. Or a goatherd. Or an olive-grower. Since I am not – and am never likely to be – I have had to find other ways to fuel my fantasies: through travel.

People travel in different ways. Some enjoy cruises; others like to be led through cities by guides waving bright flags. I have an abhorrence of travel that ticks boxes. “Have you done the Cinque Terre?” asks a man who plans to squeeze it in between Venice and Florence. “We’ll only have a day, but we also want to spend two days in Rome.” Two days in Rome? I curb my tongue.

I travel differently. My happy place is settling in for several weeks in a remote hamlet far from the madding crowds, where I drink local wine at the local bar and use local transport.

Ten years ago, on the eve of my 60th birthday, I signed up for the first of many stints as a wwoof-er in Italy, which involved scaling olive trees (it’s like riding a bike; you never forget), grape picking, grubbing weeds and debating politics around the family table.

Two years ago, I joined a bunch of mad Sicilians and a herd of sheep and goats to complete the transumanza – an ancient practice in which stock are moved during the warmer months from the valley pastures to the high alps. I once worked in an Italian food market, selling salami, which gave me new respect for shopkeepers.

The idea for running a second-hand bookshop came from a radio programme two years ago. I heard an interview with Jessica Fox, the young woman who set up The Open Book. I contacted her the same day and signed up. The waiting list was two years. It’s now three. The bookshop experience is booked through Airbnb, but the shop is run by the Wigtown Festival Committee, which stages a hugely popular annual book festival in September each year.

“The residency’s aim is to celebrate bookshops, encourage education in running independent bookshops and welcome people around the world to Scotland’s national book town,” says the Airbnb listing.

Previous tenants have included librarians, retired couples, a single woman from Korea, who spoke little English, and a couple of musicians who call themselves The Bookshop Band. They liked the place so much, they returned to live in Wigtown this year.

I can see why. I’ve already made inquiries about next year’s festival.