4 common design errors you’re making on your small farm and how to avoid them

When a block has a design fault it can seriously affect the practical aspects of growing plants and livestock.

Whether you are new to living on your block or not, you may become aware that things don’t seem quite right. Maybe you are exposed to unacceptable wind levels, vegetation is not in the right place, the place lacks cohesion and legibility, or is a mish mash of styles that create more work than pleasure. These are some common landscape errors to avoid or correct if possible.

1. OVER-DESIGNING

Understanding and working with nature is the preferred method, proven to be the most successful environmentally and financially. You may have heard the term “less is more”. In landscape architecture circles it has become an overused, little understood piece of jargon bandied about by intellectual snobs, but it is well worth taking on board when designing a block.

While an uncomplicated overall structure requires a degree of design, an understanding of ideal dimensions for shelterbelts, horticultural requirements of certain species, optimum path widths, roads and linkages, make sure to allow some leeway for your design to evolve as it would in nature.

Everdien’s tips:

– Unless you want to become a slave to your property, work with nature and don’t try to outwit her.

– Make sure that you address structural planting before addressing the detail.

– Have a broad plan in mind before succumbing to impulse buying of plants.

– Leave a bit of leeway for nature to take over.

2. SHELTER

Make sure that all your shelter requirements are within the confines of your property and comply with your District Plan rules on setbacks. A personal experience highlights some avoidable design errors. I have always been aware of the damaging effect the wind has on plants, bee activity and the ambience of a place.

When we bought our block of land there was mature planting on surrounding properties protecting us from all angles. Only a 90 metre long immature west shelter belt belonged to us. Prior to building our house, we spent time planting fruit and nut trees and expansive gardens, adding to the property’s lovely enclosed sheltered feel.

However that was not to last: within weeks of moving into our house, neighbours to the south-east of us felled their 30 year old pine tree stand. This changed the sense of enclosure and altered the airflow, creating new wind eddies.

The following year the neighbours to the west of us removed mature poplars and pines which increased wind velocities onto our west boundary, creating new wind flow patterns along the east of our property. Fortunately, a lovely stand of mature pines and gums were still standing on the property to the north- north-west of us… until the following winter when all of these trees were also felled.

This had the effect of rendering our now established western shelter only barely sufficient because the loss of trees there shortened the optimal shelter length. Then, as if that wasn’t enough, a neighbour to the south-west of us asked us to remove nine of our western shelter belt trees so that he could get more winter sun. How could we refuse?

This produced a wind funnel sweeping around the hill from the west. I am now busy infilling the gap further down the slope so that any new plantings will lengthen the shelter belt without affecting the neighbour.

Everdien’s tips:

– Make sure that you are not depending on neighbour’s planting for shelter.

– Make sure that you don’t create a venturi effect (like a funnel) by having gaps between solid areas of planting.

– Make sure you are familiar with your council’s District Plan rules and consent requirements regarding shelter belt offset distances.

– Make sure the shelter belt will not block out your or your neighbour’s sun once mature.

3. WRONG PLANT, WRONG PLACE

Make sure you plant species that are suited to the latitude and altitude you are in. One sure way of creating work and frustration is to set yourself up for failure by planting species that don’t belong within your latitude and altitude zones, soil type and environment.

Some common mistakes include:

– Trying to grow semi-tropical species in temperate regions. Unless you have a frost-free microclimate, don’t do it.

– Growing cool temperate species like cherries in a warm temperate zone.

– Growing species for autumn colouring and/or cool climate conifers in coastal, semi-tropical warm temperate zones. This never really looks good.

– Trying to grow species that love acid conditions in soils with a high pH.

– Planting species that are so vigorous that at some stage down the track you will be faced with culling them at considerable cost and frustration.

4. INCONGRUENT DESIGN ELEMENTS WITHIN THE LANDSCAPE

Make sure you work with the landform and have elements appropriately positioned. This is where fences, shelter and structural plants don’t fit into the landscape. A common mistake is to plant on ridgelines and to have hedges and shelterbelts that run in a straight line over contoured land.

Remember to keep straight lines and formal treatment close to building structures, transitioning to free-form further away. Failure to create a multi-dimensional space is a common one. Remember to position well-spaced limbed-up large trees in the foreground. This creates ever-changing points of reference and separate vistas as you walk through a space.

Everdien’s tips:

– Make sure to avoid a mishmash of design styles and plants from a wide range of origins leading to a busy confused space.

– Ensure that you keep warm and cool toned colours separated. Be careful with the use of golden and variegated plants.

– Make sure you have places that provide ‘rest’ for the eye like lawns.

– Aesthetics follow scientific and mathematical principles of scale, rhythm, cadence and perspective. If designing an avenue, the height of the trees versus the width of the road or path must be correct in order for it to work.

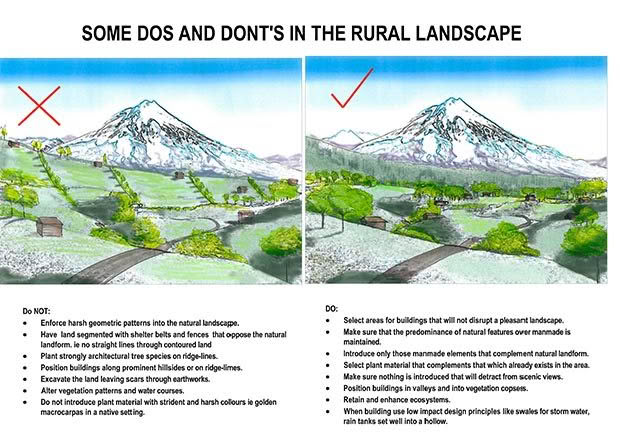

DOS AND DONTS IN THE RURAL LANDSCAPE

Do not:

– Enforce harsh geometric patterns into the natural landscape.

– Have land segmented with shelter belts and fences that oppose the natural landform, ie no straight lines through contoured land.

– Plant strongly architectual tree species on ridge lines.

– Position buildings along prominent hillsides or on ridge lines.

– Excavate the land leaving earthwork scars.

– Alter vegetation patterns and water courses.

– Introduce plant material with strident and harsh colours, ie golden macrocarpas in a native setting.

Do:

– Select areas for buildings that will not disrupt a pleasant landscape.

– Make sure that the predominance of natural features over man-made is maintained.

– Introduce only those man-made elements that complement natural landform

– Select plant material that complements that which already exists in the area.

– Make sure nothing is introduced that will detract from scenic views.

– Position buildings in valleys and into vegetation copses.

– Retain and enhance ecosystems.

– When building, use low impact designs like swales for storm water and set rain tanks into a hollow.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION

Contact Everdien of Epsilon Environmental Designs by phoning 06 345-0737, emailing info@hiralabs.co.nz for a landscape questionnaire, or check their landscape blog www.hiralabs.co.nz.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.