Life of naturalist and illustrator Sheila Natusch celebrated in new documentary

New Zealand naturalist, writer and illustrator Sheila Natusch brought science to the people. A film about her life captures her love of the natural world and her unconventional and indomitable spirit…

When New Zealand naturalist Sheila Natusch was invited to take part in the venerable Royal Society’s centennial celebrations in 1967, she found she didn’t own an evening gown. Her only suitable dress had been converted into a cushion cover some years before. Ever thrifty, Sheila, then aged 41, unpicked the cover, boiled it, resewed the seams, and brought it back to life.

The anecdote reveals a lot about the woman who is one of New Zealand’s most talented – yet unsung – natural science writers and illustrators. “She didn’t hold with finery or formality,” says Christine Dann, who has produced the film, No Ordinary Sheila, due for general release this month (October). “Her focus was entirely on the exploration and enjoyment of the natural world.”

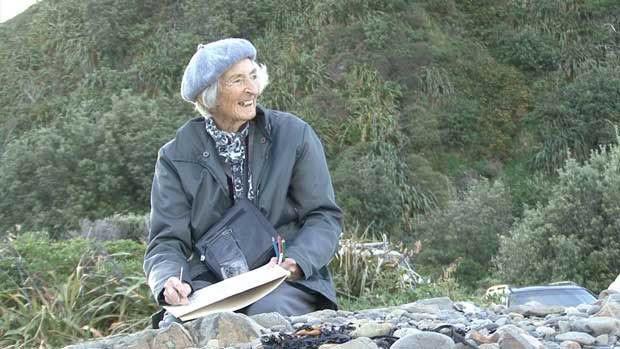

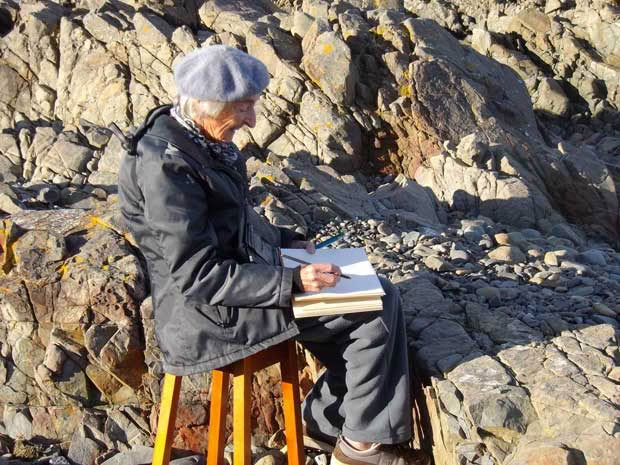

Christine Dann on location with Sheila.

Christine spent three years working on the documentary with film-maker Hugh Macdonald, Sheila’s cousin. A writer, cook, eco-gardener and feminist herself (she wrote Up from Under about women’s liberation in New Zealand), she was drawn to her subject because of their shared interests – and because of Sheila’s indomitable spirit. “She had such passion for her subjects. She spent her life learning. In the last year of her life (she died in August, aged 91), she had a Brazilian caregiver, so she set about learning Portuguese.”

Sheila grew up on Stewart Island, the daughter of the island wildlife officer. In the film, she recalls he had a “volcanic” temper, but he also fuelled her love of nature. She spent hours exploring the island’s shores and bush, sketching what she found. Christine says Sheila also inherited her mother’s talent for art. At school, and university, she was clever at sciences and the arts, especially languages.

Sheila on top of Carrington Peak in the 1950s.

Like New Zealand writer Janet Frame, a close friend, she benefited from an education system, which, at that time, had a strong tradition of shaping girls’ education. Sheila and Janet took long walks on the beach and discussed books over tea and toast by the fire. Sheila was the first person to read Janet Frame’s manuscript of Owls Do Cry.

Sheila circa 1950 checking a map while walking the Mason Bay Track

Christine says while Sheila studied botany, biology and geology, she never wanted to be a scientist. “Her interest was in bringing science alive for the general population, through words and illustrations – in making it accessible to people. She was always being told off for drawing things that moved, rather than static and dead creatures with borders around them.”

Over her lifetime, she produced more than 30 books, including the best-known Animals of New Zealand, plus books about Stewart Island, Iceland (for which she had a special passion) and The Cruise of the Acheron, a boat that surveyed the coast of New Zealand in the 1840s and 50s.

Christine says Sheila’s depiction of wildlife was scorned by some traditionalists at the time, who thought it too simple. “In fact, she was well ahead of her time. Today the emphasis is on ‘citizen science’, making science accessible to all people. She was trying to convey the joy of nature beyond the science community.”

In 1950, Sheila married Gilbert Natusch, an engineer with the Ministry of Works. They shared a love of the outdoors.

“Sheila once said that the person she married would have to be able to swing an axe and carry a 60lb pack,” says Christine. While Gilbert could do both those things, he also made it clear he did not want children. Sheila said, “If I can’t have babies, I’ll have books.”

Sheila on her wedding day in 1950.

For their honeymoon, they stayed in a tin tramping hut and were joined by Gilbert’s mate, Andy. The couple also cycled 1200km on old-fashioned push bikes along gravel roads and tracks from Picton to Bluff, with only sleeping bags for shelter. Later in their marriage, they walked at night, sleeping under the stars. “She was hugely intelligent, but she had a child-like wonder of the world,” says Christine.

Christine says when they began the documentary, Sheila was 88 and they realised it would have to be done on her terms. “It was more about conversations than formal interviews.” She would visit her at her home at Owhiro Bay in Wellington and take gifts of food like Carrageen Pudding, made from milk set with seaweed. “Cooking was not Sheila’s strong point. For her, the best oyster recipe was straight off the rocks, when she rowed around the bays.” Sheila also wrote a book on foraging for food (Wild Fare for Wilderness Foragers) in 1979, well before foraging became fashionable.

Christine says Sheila’s legacy was “to be inspired to conserve nature, one needs to know its beauty. She even thought jellyfish were beautiful. She believed that studying the natural sciences should start at kindergarten, when children begin on the path of discovery.”

Sheila Natusch died on August 10, days after she attended the packed-out premiere of No Ordinary Sheila at Wellington’s Paramount Cinema.

No Ordinary Sheila opens in New Zealand cinemas on October 19.