Artist John McLean’s coastal orchard in Mimi, Taranaki

John & Chris McLean

Artist John McLean was driven by need to become self-sufficient 30 years ago, but today he and wife Chris couldn’t live any other way.

Words & Photos: Helen Frances

Who: John & Chris McLean

Where: Mimi, 40km, north-east of New Plymouth

What: 14ha (35 acres)

Web: www.johnmclean.co.nz

The camera-shy chooks are let out at lunchtime into a controlled space, skedaddling past as John McLean begins the guided tour of his garden. The vegetable beds are inside separate fenced areas with interconnecting gates. When the flock finish eating out a garden bed, the couple let them in to scratch around and help prepare the soil for the next planting.

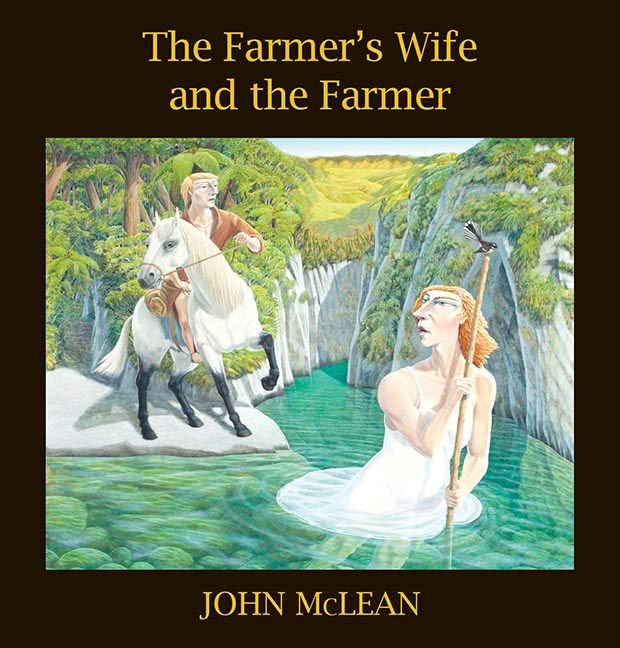

John, an accomplished artist, and wife Chris have lived for 30 years almost self-sufficiently at Mimi Farm in North Taranaki. It’s no surprise that his first foray into writing, a wonderfully illustrated book entitled, The Farmer’s Wife and the Farmer: a painted New Zealand Odyssey, should be firmly anchored in the land and the raw realities of farming practices.

“We usually have about a dozen hens, but hatch chickens under a broody hen and keep the rooster quota out of that until they start crowing, at which time I wring necks and pop them in the freezer,” John says. “Five have just begun yodelling in the last couple of days which is a mistake on their part.”

The camera shy chooks.

As the tour continues, pumpkin plants tumble along the ground all around you. There are cucumbers and zucchinis, tomatoes, celery, kale, massive cabbages and caulis, herbs, kumara, carrots, corn, peas and potatoes. There are blueberries, apricots, strawberry beds, oranges mandarins, feijoas, pears, and persimmons laden with orange flowers.

The self-sufficiency practices carry over to their house. John built it out of largely recycled, natural timbers. A retired friend living with them at the time worked with John to help frame it up and close it in, and John finished it from there.

“It was a long-winded way of doing it but it meant we could do it without debt and in the long run that really counted,” John says.

The beams are from a dairy factory, recycled doors from various places, and the stairwell is lawsoniana (Lawson cypress).

“I went on a working bee at the local school and they were cutting down a hedge so I grabbed the logs. They were only little logs but they were enough to do the stairwell. It’s beautiful timber. There’s a lot of macrocarpa in the house and the ceiling is matai.”

When he hasn’t been working on the land, John has earned a living as an artist. The garden around the house is the backdrop for several of his sculptures, and his gallery sits next door to the house. Inside both are a number of his evocative canvases.

Most of the heavy work is now done by a lease farmer responsible for the farming operation, leaving John and Chris – who makes art assemblages with found objects – time to concentrate mainly on their art.

John says when he started painting, it was ‘abstract-expressionist composition”, now it’s more ‘figurative’.

“We keep the one kilometre drive in good order, maintain the fruit trees and individual gardens, deal with pest trapping in the conservation land (stoats, ferrets, rats, possums), do the firewood trees and shelter trim clean-ups after the contractor has been through, and fence maintenance.”

The McLeans co-own the farm with their neighbour, stone sculptor and furniture maker Howard Tuffery. They share an orchard, a small flock of four to six sheep and lease another 10ha (25 acres) of grazing land. Over the years they have planted native trees and shrubs, securely fenced the steep areas, wetlands and the river’s edge to exclude stock, and covenanted around 5ha (12 acres) to the QE11 Trust.

The couple have planted thousands of natives around the estuary that borders their property, and covenanted land to protect it forever.

They recently planted 400 flax in the wetlands, the last of their conservation planting.

“When we came here there wasn’t a tree on the property so we planted thousands all around the river and the little inlet and down the banks. We did that all off our own bat and then in the last few years regional council has provided trees, which has been really good,” Chris says.

Almost everything they’ve planted is native, apart from some avocados which grew like weeds from stones they threw down the bank. The estuarine is all natives, and they have found some specialized coastal species growing there, including native celery, sea primrose, pingao, shore lobelia and tree daisy.

The regional council designates the estuary as a place of special significance John says.

“They recognize that it is very rare to have an estuary that hasn’t been built all around due to lack of access.”

The tree planting brought an abundance of bird life, including a lot of special guests when the kowhai and flaxes are in bloom.

“We have tui like blowflies around the place,” says John.

Kereru, bellbirds, fantails and hawks abound, there are shining cuckoos, grey warblers and many different seabirds, some of which are vulnerable species. Northern New Zealand dotterels, Caspian terns, oystercatchers, shags, little blue penguins and recently royal spoonbills visit the estuary.

They come for the fresh food, including whitebait and other fish, but it’s more than that. John and Chris recall an impressive event during the commemoration of the neighbour’s family gravesite, located on the pa on their land.

“We had a bit of a hui over there and at the time the stone was installed two white herons circled overhead then flew away,” John says. “At first we thought they were spoonbills but they were heron. The [Anglican] Maori priest said “it’s a sign,” and he was totally unphased by it.”

Topography and ecology has changed over their time here. Rising sea levels and tides washed away once massive sand hills, uncovering extensive pipi beds and the remnants of Maori canoes which they took to the museum and had dated to circa 1300. They also discovered “really old-looking hangi pits” buried under layers of ash from volcanic eruptions.

John’s stone sculptures dot the garden. His work has also featured in big feature films including The Last Samurai and The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe

“We wouldn’t have bought the land without the blessing of local iwi (Ngati Mutunga) because this is a pa site right in front and there’s another one over there,” Chris says pointing to a promontory. “Nowadays we wouldn’t even be able to build here. John went to the local kaumatua to say we were interested in buying the land (from farmer Peter Herman) and he gave us his blessing. When we were deciding where to build the Maori people walked around with us and said, ‘Build where it feels right in your heart.’ When the house was in scaffold they clambered all over it and blessed it and sent away any spirits. This is their rohe. We keep them informed about anything that’s happening on the land.”

Both John and Chris come from families that grew their own food. Chris’s parents emigrated from Switzerland when she was nine, and they grew up together in Tauranga. The couple married when John was teaching in Auckland, then moved to Te Akau soon after in 1969-70, where they developed a feeling for the rural, self-sufficient life-style.

John’s passion was art, not teaching, but his parents wanted him to get a “real job”. His father was a carpet layer and his mother, unusually for the time, also worked outside the family.

“They were pretty poor. It was an era where they had come through a world war and depression. A lot of children whose parents were tradespeople were given opportunities they hadn’t and my parents didn’t understand art – it wasn’t part of their life at all,” John says.

He rose quickly in the teaching profession, was promoted to a position in Taranaki and earmarked for higher things, a coveted job in the Education Department. Then in 1976, depression struck.

“I felt torn down the middle because I recognized if I took that next step professionally I’d never ever know this (he gestures around the gallery). I was 30 years old (he is now 71). There had to be a breakdown – it was like an ocean liner by the time it slowed down. Basically I got cut off at the knees and had to take three months off school.”

John in his on-farm gallery with some of his works from the last 40 years.

John returned to work, teaching art part time at a high school and doing “sundry jobs to make a crust.” But most importantly, he started painting seriously, and spent recuperative time with artist Michael Smither in his studio.

In 1978 the McLeans moved to their first small cottage down the road from Mimi Farm. They were driven by need to engage in a self-sufficient lifestyle by their limited income and having three children to raise.

Then an art gallery owner spotted John’s work, held some exhibitions and his career as an artist began to take off. John has exhibited and sold works both internationally and throughout New Zealand.

The farm, landscape and country characters of North Taranaki inspire his imagery. Blending everyday realities with his imagination through experimental painting processes, John’s work has a mythical quality that resonates with universal themes of human endeavour.

In his book, John takes readers through the New Zealand landscape with Constance and Thomas on their separate journeys of self-discovery. They encounter some strange folk – a traveller on his white horse, Cloud, a lost tribe, a blind boatman and his sighted twin – a process that proves as transformational as the life story of John their creator.

The Farmer’s Wife and the Farmer: a painted New Zealand Odyssey

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.