Take a tour of Photographer of the Year Tracey Scott’s century-old Rotorua villa

Tracey with, her chihuhua/foxy cross, May.

When Rotorua photographer Tracey Scott looks through her camera, she sees possibilities – not problems – which is also her metaphor for life.

Words: Venetia Sherson Photos: Tessa Chrisp

For a portrait photo of herself, Tracey Scott would wear jeans, a checked shirt and her grandmother’s jewellery. She would have a book and a bunch of old English roses beside her chair, a small dog at her feet and, on the walls, framed photos of her girls. Through the window would be more roses and a dark bay horse. Tracey would be pictured looking directly at the camera, one eyebrow raised.

The old villa was the only house Tracey could afford, but it took blood, sweat and freezing nights to bring it back to life.

For the viewer, certain facts would be revealed; the subject likes gardening, animals, family and casual clothes. All of which is true. Today, she wears a shirt and jeans. A chihuahua-cross named May pads in her wake, and a striking photo of her daughter, Natalie, dressed in a 19th-century riding habit, stares out from the wall. And the eyebrow? More about that later.

European and Māori pieces pay homage to Tracey’s family heritage and love of Rotorua.

Tracey is a Rotorua photographer – much decorated as it turns out, although she is reluctant to brag. Two years ago, the New Zealand Institute of Professional Photographers named her Photographer of the Year; she is three bars short of becoming a Grand Master, an accolade achieved by only eight others.

Ironically, photography wasn’t her first career choice or even second. As a school-leaver, she tossed up between psychiatric nursing and fine arts. A friend of her grandfather’s, at that time the superintendent of Tokanui Hospital, persuaded her to choose the latter.

Chandeliers have replaced the harsh neon lights that lit the building when it was an antique shop, while stripped boards are a fitting frame for an 1800s kauri dresser.

At the Otago School of Fine Arts, she majored in oil painting with a view to eventually training as an art restorer. But the Dunedin course closed before she could enrol. Still convinced her destiny lay in restoration, she headed to London, where she discovered a qualification would cost 40,000 pounds and span seven years. Most students, she says, were the progeny of titled parents, for whom time and money were no object.

Stuck in London without prospects or funds, she instead completed a two-year course in photography and worked in a photo library until her work visa expired. When her New Zealand childhood sweetheart spent $2000 on phonecalls urging her to return to marry him, she booked her passage home.

Tracey in one of the deep-seated chairs inherited from her grandmother.

In 1984, a year after their wedding, daughter Natalie was born and photography was sidelined. But then her childhood sweetheart up and left. “I was suddenly a solo mum with a mortgage.” She took a job as a press photographer at the Rotorua Post, where she stayed for 20 years.

This could have been the end of the story. News photography is addictive and Tracey was well suited to the adrenalin-fueled lifestyle. She says she inherited a competitive nature and can-do attitude from her father Bob Scott, New Zealand’s first helicopter pilot.

Tracey’s portrait of her 14-year-old granddaughter Alisha pictures her with scarlet lips, a 19th-century corset and a rebellious look.

She loved the pace and energy of the newsroom and there were indelible moments, like when she trampled on some royal toes. “I was walking backwards, shooting pictures of the Queen during her visit to Rotorua. I stepped on Prince Phillip’s foot and almost tripped him up. He was very gracious.”

But chronicling tragedies and hardship took its toll. Even today she can bring to mind two stark images: one of a man sitting on concrete steps with his head in his hands after fire had razed his home; the other a fatal car accident, where after shooting her pictures, she comforted the victim’s wife. Remarried, she decided the time was right to leave news photography. “I thought I would paint for a while, but my art was very dark. It was like an outpouring of emotion.”

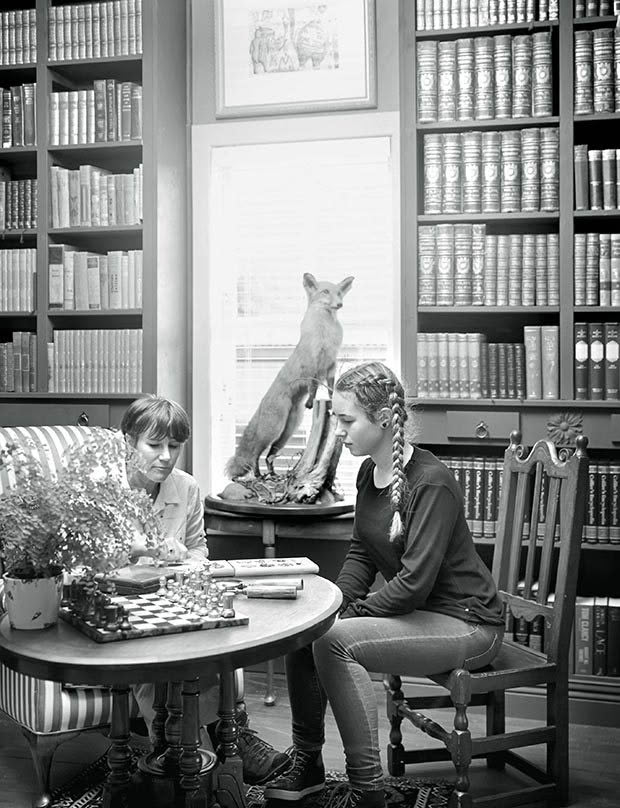

A stuffed fox, bought for Tracey by her mother, watches a grandmother and granddaughter play the ancient game of Mancala in the library.

She put away her canvases and considered other options. Serendipitously, a friend asked if she would take pictures at her wedding. “Weddings are such happy places,” she says. “As a news photographer, everyone hates you; as a wedding photographer, everyone loves you.” She also joined the Rotorua Camera Club, and met a group of talented and like-minded people who thought outside the square.

“It was like painting again. You begin with a blank canvas. Anything is possible.” She divided her time between taking her own photos and – to make a living – shooting happy couples.

Tracey’s grandmothers copper bottomed pots hang in the kitchen.

About this time, her second marriage ended and she was again left with reduced funds, and needing a house. The only place she could afford ($250,000) close to town was a century-plus-old villa posing as an antique shop. She’d been there many times to buy antiques. She describes it as a mess. “It had only one light switch, which activated fluorescent lights in every room. There was no running water other than the toilet, no kitchen and no heating.” Her mother told her she had rocks in her head.

But through her lens, the photographer saw possibilities. The house had strong bones made from hand-sawn rimu and kauri, high ceilings, and the potential to create a library with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. She bought it, and began the transformation, surviving the cold nights by sleeping under three feather duvets, with an electric blanket and a woolly hat. Ice formed inside the windows. “The builders used to go outside to warm up.”

Elements of the bold, the beautiful and the bizarre tell the story of Tracey’s life. Desks are for contemplation and writing, chairs for reading.

She rose at 5am to shower at her mother’s apartment, before starting work. She also bought a wall plaque with the words: “Life isn’t about waiting for the storm to pass; it’s about dancing in the rain.”

Five years on, chandeliers have replaced the fluorescent lights; the kitchen is transformed into a homey and light-filled space and her grandmother’s china is displayed in a cabinet.

The Swiss Victorian Eastlake bed was a gift from Tracey’s mother. “It looks a little devout,” says Tracey. “But it is very beautiful.” The American brass and crystal bed lamp weighs a ton, she says.

While the house has had a long history, it now reflects Tracey’s own stories. In the entrance hall are riding boots and a velvet riding cap worn when she competed in dressage events; there is a carved bone from a marlin’s nose, which she hooked in Tonga; tucked away in her bedroom is a collection of erotic Japanese netsuke.

Instead of a television (“no time for it”), there are board games like Mancala, an ancient game played with stones or beads. There is no dishwasher, and the clothes drier is a ceiling-mounted wooden drying rack. “The house is my sanctuary,” she says.

The rabbit with a gun starred in a award-winning photo that also featured May, as the rabbit’s prey.

It is also now an Airbnb, since a friend persuaded her to share the house with guests. “Every guest has been wonderful. Except for this one guy, who arrived carrying a six-pack of beer. He seemed to be getting flirtatious and I had to think how to put him off.” She left the room and fetched a Bible – which she was reading at the time – “just because I’d never read it”. Her guest asked what she was reading. “I said, ‘it’s The Bible’, and I opened it.” He went off to bed.

So, what about that raised eyebrow? Does it suggest a woman who views life through a sceptical lens? Does it register displeasure at some of life’s curve balls? She opens a portfolio of images, shot in black and white.

Tracey bid online for the tin plate with the Māori woman’s portrait. “I paid far too much for it,” she says.

In one, taken at a wedding, guests are in the background faced away from the camera, deep in animated conversation. In the foreground, a woman sits alone on a bench, holding an empty glass.

She looks bored or sad or both. A child beside her seems utterly defeated by weariness. “It was supposed to be a happy occasion, but for these two it was clearly not,” she says. These are the images to which she is drawn. “I always see life through a lens. It is both a trial and a pleasure.”

Tracey’s images, including one of May, caged and wearing wings, titled My Fallen Angel. “It was after she’d been naughty,” says Tracey.

The raised eyebrow, it turns out, indicates an insatiable and never-ending quest to uncover people’s stories. She points with delight at a portrait photo of her granddaughter – a beautiful, fair-haired teenager, staring directly at the camera. “You see. She has it too.”

Stormy skies, stormy eyes: A shot taken by Tracey at an abandoned orphanage in Putāruru.

Tracey’s tips for portrait photography

1. Talk with the subject at length. Get a feel for their life, past present and future. Get to know who they really are.

2. Either keep the background clean and clear so it’s all about the person, or give equal weight to the environment to help explain something more about who they are.

This young girl, in a southern village in Ethiopia, was already betrothed to be married.

3. The subject’s expression is very important. It can tell the viewer how they see the world.

4. Light is everything, and it can change the mood of your image. Make sure your lighting is in keeping with your message.

5. Be true to yourself as an artist. It’s your vision; your personal interpretation of the person. Try not to copy others, but take the image in a way that speaks to you.

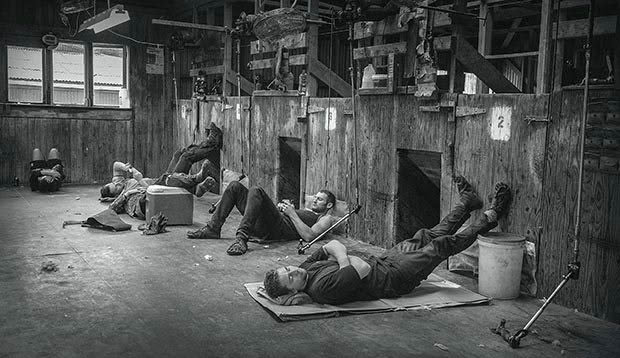

Lunch break at a shearing shed where the shearers take every chance to stretch their backs and legs. Tracey says black and white images lead the viewer to focus on the story without distraction.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.