How to deal with a broody hen

Silkie bantams are one of the poultry world’s best mothers.

Spring can be a confusing season for the flock owner who wants eggs, and equally confusing for hens who want to be mothers.

Words: Sue Clarke

Spring means more hours of daylight and warmer weather, and it all turns your bird’s thoughts to reproduction.Spring means more hours of daylight and warmer weather, and it all turns your bird’s thoughts to reproduction.

Whether you have a rooster or not, your hens will have egg-laying and incubation on their minds or, as it’s known in the poultry world, will probably want to go broody, clucky or ‘on the cluck’.

In this article we will cover:

• the physiological changes which are triggered that start the reproductive cycle;

• how to deal with a broody hen if you don’t want her to incubate eggs;

• how to deal with a broody hen if you do want her to incubate eggs.

The conditions which are needed to encourage a hen to begin to ovulate and lay eggs include the following:

• Being exposed to a day length of at least 12-13 hours which is steadily increasing;

• Being at a correct weight for her age and breed if she is a young pullet starting her first laying season;

• Being on a high enough plane of nutrition to be able to portion some of her intake to developing ovarian tissue instead of just eating enough to maintain body condition and growth;

• Having moulted during the offseason and regrown a full set of new feathers;

• Having a safe and secure, preferably darkened nest area, with perhaps artificial eggs to entice her to use it.

CONDITIONS WHICH WILL MAINTAIN EGG PRODUCTION FOR AS LONG AS POSSIBLE INCLUDE:

• being of a strain or breed selected for extended egg production without going broody;

• having increasing day length up to 16 hours per day and then maintaining that day length;

• providing sufficient quality feed to both provide for body maintenance, warmth and produce one egg per day.

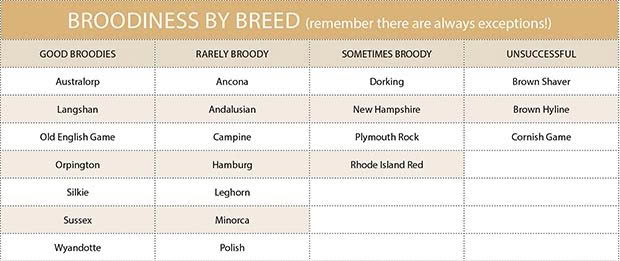

If you choose to encourage egg production over broodiness you will need to either choose a breed not prone to broodiness like commercial layers or heritage light breeds such as Leghorns, or learn how to recognise a broody and break her of the habit as quickly as possible (more on that below).

You can also choose to extend the natural summer day length of 16 hours, once the days start to shorten after the longest day (December 21) by adding an artificial light source which can come on early in the morning or in the evening, but preferably both ends of the day. A light coming on at 5.30am and going off at sunrise and then coming on before sunset and going off at 9.30pm will give your hens 16 hours of daylight and maintain their egg production.

WHERE ARE THE ROOSTERS IN THIS PLAN?

Reproduction means the males will respond to the same stimulus that brings the hens into lay, so if you want to have fertile eggs you must look after the boys with as much care as you offer the hens.

Day length has the same effect on sperm production as it does to ovulation. They may continue to crow and show rooster-type behaviour as they feel the effects of spring, but won’t be fully fertile until the hens are at the point of laying their first eggs.

EGGS ARE GO

Once you have your pullets and hens in lay, and assuming the conditions of food and day length are favourable, the number of eggs a hen lays will be dependent on genetics. A hen’s natural inclination is to lay a clutch of eggs: these are eggs laid on consecutive days without a break that she can then sit on and hatch. The difference between the first egg laid and the last may be as long as 10 days but the eggs don’t begin to develop until the hen sits on them, raising the temperature which stimulates the cells inside to grow.

Good layer hens have a 24-25 hour egg formation process and can lay 30 or more eggs in a row without a break. Commercial hybrids like Brown Shavers have been selected for their impressive laying genes from birds which lay the most numbers of eggs in a clutch, lay many clutches and are not prone to broodiness. Good egg-laying breeds may stay in lay without going broody, but lay fewer eggs on consecutive days.

Some of the light breeds like Leghorns and Minorcas are not very prone to going broody and will also continue to lay without a break for lengthy periods. The heavy breeds tend to be more prone to smaller clutches before they take a day off and some individuals may only lay one clutch of 12-15 eggs before they stop and go broody. This is natural behaviour for many bird species, including the wild fowl from which our domesticated poultry are descended.

LEAVE IT TO THE BIRDS

If your bird’s eggs are fertile – we’re assuming you have a rooster – then let the hen sit on a suitable number for her size and put her in a safe and secure place right from the start. Don’t let her sit on eggs in the normal egg-laying nesting area as this prevents other hens using it, and they will add their own eggs, hampering the efforts of your hen to sit on her clutch.

Ideally, you want to move a broody hen to her own nest in another part of the coop, or better yet to her own portable run that is rat and predator-proof. Move her during the evening and give her a couple of artificial eggs or golf balls to settle her.

Once you are confident she is sitting tight, introduce the eggs you want her to hatch. If she is a first-time mother, just let her hatch what she can and see how she performs as a broody and as a mother. Her performance (or lack thereof) will give you an idea of her suitability to be a good ‘clucky’ and whether you can trust her with hatching eggs in future.

BROODINESS

Broodiness is a natural instinct whereby a hen determines she needs to sit on a nest to hatch chicks. Broodiness is a natural instinct whereby a hen determines she needs to sit on a nest to hatch chicks.

Once she is nearing the end of a clutch of eggs her pituitary gland releases the hormone prolactin which causes her to stop laying. Her body prepares for incubation by increasing the blood flow to the skin of the brooding area over her breast bone. This area may become warmer by up to 2°C.

All this means she will stay broody and not lay, even if you remove eggs from under her or put other objects in the nest like artificial eggs, golf balls or even lemons!

Some hens are much better than others at sitting tight for the required length of time to hatch eggs, so it pays to make sure she is a good sitter before you entrust her to hatch eggs, particularly ones you have bought from a fellow breeder.

The change to ‘broody’ can be quite subtle to start with, so if you don’t want your hen to sit, the quicker you are to spot her and attempt to dissuade her, the more successful you will be.

She may start to show signs of starting to go broody before she has laid the final one or two eggs of the clutch. If we refer back to the wild, a hen will go and add an egg per day to her chosen nest, but not sit tight and warm them all up each time. Once she ‘sits’ and commences incubation then all the eggs laid will warm up together and start development so they will hatch within a few hours of each other. Broody signs include:

• a hen sitting on the nest in the late afternoon;

• not wanting to get off the nest;

• fluffing out her feathers and clucking at you;

• if you lift her off she may just run off, but tomorrow she will be there again;

• she may squat when you lift her off the nest and sit her back on the ground;

• she may make some angry clucks and peck at your hands.

Now is the time to act if you don’t want her to sit on eggs before her ovaries cease to function.

SUE’S TIP

Broodiness is a sex-linked characteristic, passed on to pullets through their sire. You can select for the trait by breeding from cockerels with excellent broody mothers, or by never keeping eggs from hens which show a tendency to go broody after only a few eggs.

HOW TO STOP BROODINESS

Over the years I have heard some weird and often cruel methods of stopping a hen being broody, including standing the bird in a container full of cold water up to her feathers, and hanging the bird in a sack from a tree in a sack. These are not humane options, and they won’t work. A brief period in cold water or hanging her in a sack is not going to have much effect on her body systems except perhaps stress her into a partial moult.

What you need to do is provide her with a less-than-comfortable situation for a number of days which will reduce her body temperature.

The best option is to have a cage or hutch with a wire floor. A large, wire pet cage or crate, sitting up off the ground on bricks or wood, will keep cool air circulating on her undersides even if she chooses to sit down. It needs to be in a draughty spot, but not exposed to the weather and elements. Keep the cage within your chicken run or in an open shed, and give her food and water. Keep her locked up for four days.

If after release she goes back to a nest, put her back in the cage/crate for another four days. But you should find, if she has been broody for only a day or two, four days tends to work.

If you have left her sitting on a nest for more than a week, then it is going to take about two weeks to stop her broodiness, and then at least a month before her ovaries will start producing eggs again.

You can put several broodies together in a pen or run if there’s enough room. Be aware of the pecking order though, as hens can be quite vicious to each other.

Some breeds are better at motherhood than others. Some of the heavy heritage breeds can make excellent mothers and can easily cover 15 or more eggs and hatch them successfully.

Bantams make some of the most consistent and reliable mother hens and their capacity is only limited by their size. Silkies have the best reputation, but be aware that their chicks can sometimes become tangled up in their fluffy breast feathers, especially when the feathers are wet.

SORTING FERTILE EGGS

If you are keeping fertile eggs aside in readiness for hatching, writing on them is the easiest way to keep track of what you have.

• Use a pencil to write the date of lay on each egg.

• Store them pointed end down in a cupboard or area with a temperature between 12-16°C, with not too much fluctuation.

• If you need to save them for more than a week until you have enough, turn them pointed end up one day, then pointed end down the next and repeat until you put them under the hen (or in an artificial incubator). This prevents the yolk drifting to the top and keeps it centred.

• After a week, stored eggs will gradually lose their ability to hatch.

• In favourable storage conditions, so long as you continue to turn them daily, fertile eggs will keep up to three weeks and still hatch, although your hatch rate will be lower than with fresher eggs.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.