Video: Sculptor Ben Foster talks about his Kaikoura home and creating his amazing faceted art works

Sculptor Ben Foster talks about creating his amazing faceted art works

Between the mountains and the sea, sculptor Ben Foster and environmentalist Sabrina Luecht have found the best of nests.

Words Jane Warwick, Photos and Video Rachael Hale Mckenna, Video edit Milla Novak

On the radio, the music jerks in and out of frequency on a hiss of static. Above there is a watery sun; in the valleys below, the tendrils of a morning mist. In between, the road winds down to the coast, down to an icy, baby blue sea. There are scarred hillsides, fallen boulders, and trees with snapped branches hanging by their roots.

Ben Foster needed a home – and he found it in Kaikoura. Archie (2) also needed a home – he found it with Ben.

The roading gangs are already at work; the traffic management crews flip their signs back and forth – stop/go, stop/go, stop/go – and blow on their icy fingers. There is a slalom of traffic cones, a narrow, hewn tunnel that would have larger vehicles sucking in their engines, some cracked and sunken corners and finally the little township of Kaikoura, now shunted over a metre further north since New Zealand’s largest (but one) recorded earthquake.

Sabrina wanted a dog, a small one that a landlord would accept, and so she bought Fox (8). One day while out walking, an SPCA officer asked, “I don’t suppose you have room for another?” Ever the rescuer, Sabrina said she could always make room and so she welcomed Benny (13) – there he is under the couch. He was followed by shy and easily startled James (11), who came via K9 Rescue.

Kaikoura is linked tenuously to the rest of the country by a single road – arriving at one end of town and departing from the other – but its stories could support a highway. This particular tale is about being lost and found, being rescued and being the rescuer, of adventure and serendipity.

Ben Foster’s tale starts not that far from Kaikoura as the tarapunga – the seagull – flies. A touchdown at Pourerere Beach and then inland to Waipukurau, the biggest little town in Central Hawke’s Bay.

Archie, Fox, Benny and James are not the only ones to call this house home. There are two rescue rabbits in the backyard. When the Kaikoura Farm Park recently closed, Sabrina stepped up and managed to find homes for all its inhabitants. She is also a wildlife rehabilitator, caring for ill and injured endemic birds until they are releasable, and will be collaborating with the Kaikoura Ocean Research Institute regarding seabird rehabilitation.

Sabrina Luecht’s story, however, starts three seas and two oceans away (perhaps even three oceans, if you take the long way round) in Berlin, Germany’s capital. Sabrina’s mother taught her daughters compassion from an early age. She would take them off to the Hamburg meat market to buy live rabbits and ducks waiting to be sold for the pot, and then hop on the train home to Berlin. Their apartment was adjusted to house all sorts of creatures, and the ducks were set free in Tiergarten, one of the biggest and most beautiful public gardens in Germany.

And then one day Mama gathered up Sabrina and Anja, and they flew away, right across the world to find their own garden in New Zealand, in tiny Hokitika. It was green, wild, and remote on that far-flung west coast and it shaped the rest of Sabrina’s life. She did a BSc in zoology and set off to save creatures in need – domestic animals and wildlife, but particularly threatened birds.

If that falcon (bottom) were real, those little dogs might not be quite so casual. It is a strong piece and one that Ben will miss when it goes to its purchaser. He could – and probably will – be commissioned to make another but he would have to fall in love with it in a whole new way. Another might look identical to the casual eye but to the sculptor they are complete individuals.

After postponing her MSc, Sabrina worked for the Forest Research Institute and Environment Canterbury and then went to the North Western Hawaiian Islands as a seabird technician in charge of albatross banding for the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

She had an interlude at the Department of Conservation before navigating her way through the remote and waterlogged lowland forests of Missouri using various bird species as indicators for fragmented habitat types. She prowled the windswept shores of Tasmania monitoring shorebirds that are in serious decline; took another interlude at the Department of Conservation; monitored the rare abbots booby and many other seabirds in severe decline on Christmas Island; and then made it closer back to New Zealand’s own shoreline, working on Stephenson/Ririwha Island off Northland.

At last, she was back on her home turf for good, again at the Department of Conservation, and also at the Hutton’s Shearwater Charitable Trust and Endangered Species Foundation of New Zealand. She was all set to work in the subantarctic islands and Antarctica with Heritage Expeditions when she was offered a permanent position specializing in endangered species at the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust, a captive breeding unit that rears some of New Zealand’s rarest birds and reptiles for release into the wild.

As for Ben, at 16 he left home to do a diploma in visual arts at the Eastern Institute of Technology in Napier. It wasn’t the first time he’d left his home town. When he was five his parents packed him up along with his brother Shane and took them on the road in a house truck their father had built.

They did their lessons via correspondence school with the occasional foray into a local primary school along the way, and their seamstress mother and woodworking father supported them selling handcrafted silk clothing and bowls made from driftwood.

A few years into that nomadic existence his father had to make a new truck, a bigger one because Ben’s little sister Chloe put in an appearance. It was an enviable childhood and only ended when it was time for Shane to attend high school. So no, it wasn’t the first time Ben had left home, but this time he was on his own.

He spent one year being assiduous in his studies and wide-eyed in his leisure, and then he committed himself to the sort of dissolute lifestyle that is almost a rite of passage among young men. Despite himself, he continued to do well with respectable grades but his tutors thought he needed some life experience to inject more discipline into his work. So he answered an ad in the newspaper looking for apprentice furniture-makers, and as Ben’s artistic lean was towards sculpture and other three-dimensional expression, he could hardly have chosen better. He didn’t yet know it, but that trade experience was to become invaluable in his future.

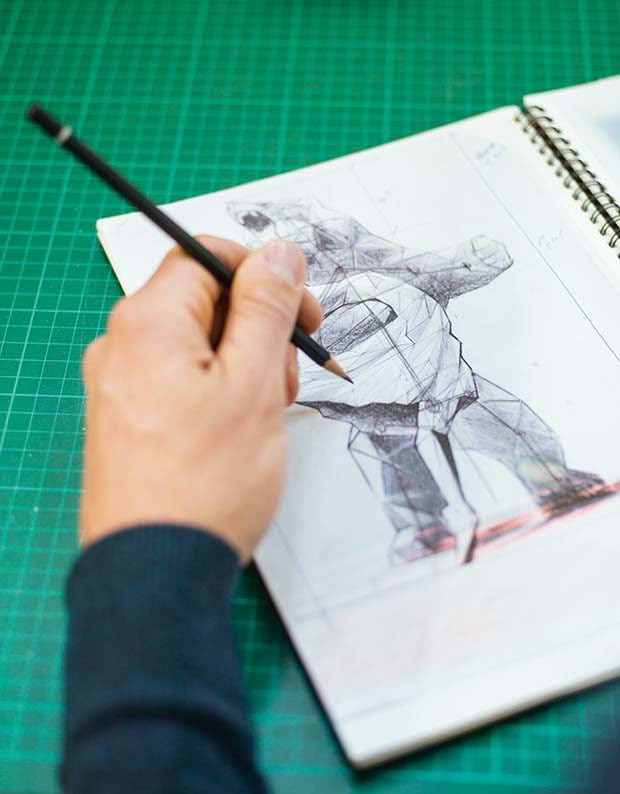

The movement in the ballerina (above, behind Ben) is extraordinary. While the dancer looks vulnerable with her throat so exposed to the bear’s jaws, the action actually implies trust, says Ben. Despite the faceted, angular construction, Ben’s pieces look astonishingly real, as if they might walk, trot, stroll, swim or fly off at any moment.

He had fun, he had adventures, not least because he was asked to help refit luxury boats, which took him to exotic ports. He didn’t know one end of a yacht from another at the beginning, but his creative talents lent themselves well to the world of custom-fits, and custom-fits led him back to his initial and intrinsic love of sculpture. He gained the confidence to return to his studies, this time at Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology, where his tutors encouraged him to reach out beyond his perceived capabilities and assured him that fine art could be a legitimate career and not just a dream.

Armed with his visual arts diploma, he set off again across the world, trying to find… what? He didn’t always know exactly what he was searching for, although sometimes he thought he saw it out of the corner of his eye, but when he turned to look full on, it always slid away. He came back to New Zealand for a three-week holiday to stay with friends in Kaikoura, a place he had holidayed in before with his family, and here it was – the place for which he had been searching. It had been there all the time in his backyard. There were the mountains he loved, running to the sea that he loved. Between the two were space and community.

Ben found himself a workshop where he could continue to make furniture to support himself and build an art portfolio to establish himself. He allowed five years for this to happen, but he didn’t even crack 12 months before he had enough commissioned sculptural work to allow him to hang up his hammer.

He asked around about galleries to represent him and settled for Sanderson Contemporary Art in Auckland, but already 80 per cent of his work was going to international clients. He was selected by an ex-pat-driven gallery in Hong Kong, which exposed his work in Asia and also to the home countries of the galleries’ investors.

So far, so very, very good, but he had not reckoned with the power of Papatūānuku, who paid a second shocking visit to Christchurch in 2011. Ben had a three-sculpture commission for a casino in Macau ready to be poured at a foundry in the stricken city, and now the business was to close. But as has been proven time and time again, Southerners are stubborn and resilient and somehow the foundry operator, with the help of two other foundries in the region, got the job done before the foundry closed its doors. It changed things for Ben, however, because he now had to look in other creative directions as there was no longer a foundry capable of fulfilling his artistic needs in the South Island.

It was a near thing, the potential loss of that commission, and made Ben realize he had to have more control over his work. He couldn’t pour hot metal himself, but maybe he could bend it. He bought a whole pile of sheet aluminium and an equally big pile of cardboard. He made patterns with the cardboard, bending it this way and that, finding its limits; finding its chi, perhaps, that energy that gives life and force. And then, he wondered, he hoped – could he transfer the result onto aluminium?

He was due to put a piece into a gallery for an exhibition named Locale and chose as his first subject one of Kaikoura’s famous seals, faceted in the way of the snowy Seaward Kaikoura mountains. The gallery scoffed, thinking a seal was not sophisticated enough a subject and too significant a change from his original works.

But Ben did it anyway. The seal piece sold before the exhibition even opened, and more new doors have since opened, with Ben still primarily focusing on faceted geometric works, which have taken him to a new realm of creativity. Right now he is working on a large-scale bear and ballerina composition for a client in Switzerland.

One retrospectively fateful evening, Ben got chatted up by a woman at a local restaurant. She was lovely; he did nothing. The encounter, however, made him realize how short life was and several weeks later he spotted the mystery woman commenting on a friend’s Facebook page.

He pondered deeply – and before he lost his nerve, he sent a message enquiring whether she had in fact been the woman at the restaurant. That short enquiry soon turned into an answer on his screen.

“No,” typed Sabrina Luecht from her laptop in Hokitika, “it certainly wasn’t me, but good on you for asking, you have to take risks in life. I hope you find your mystery woman.” The two eventually got chatting regularly and found mutual chemistry. Luckily for Ben, Sabrina is always up for adventure.

When Papatūānuku paid another visit, this time to Kaikoura and this time more violently than before, she chucked Ben right out of bed. His house bounced off its foundations and cracked around the edges; his sunroom parted company from the rest of the house, and outside there were cracks in the ground everywhere. Enter Sabrina: Sabrina who knows the power of flight, Sabrina who can engineer an escape. She chartered what was one of the few aircraft available and flew Ben and his dog, Archie, to safety on the West Coast.

And eventually, of course, they all came back together. To the little shaken house; to the place where the mountains run down to the sea, to the place they made a home.

CONNECTED

“Technology means people like us can connect with the world and not be hampered by location, or illness,” says Ben. “I can liaise directly with clients overseas, while Sabrina can continue her work remotely as a wildlife project administrator for the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust and in digital marketing roles. And so we get to live in this amazing place.”

A GIFT OF LIFE

Sabrina has various autoimmune diseases and was also diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a rare neurological autoimmune disease, for which she requires monthly blood infusions for management. Only four per cent of New Zealanders currently donate blood and the New Zealand Blood Service is desperate for more donors. nzblood.co.nz

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.