Polly’s blog: listening to the natural world

The family visit the local marae, and reap the mother of all harvests

Every now and then our hound’s sudden baying announces the arrival of Rob dropping by for a spontaneous catchup. Keen to keep this nearby resident captive, James and I are always quick to usher him indoors and get the coffee brewing. Rob, who can trace his whakapapa back 22 generations, works a little like an oral sponge. With a bit of gentle prodding, all sorts of interesting facts leak out.

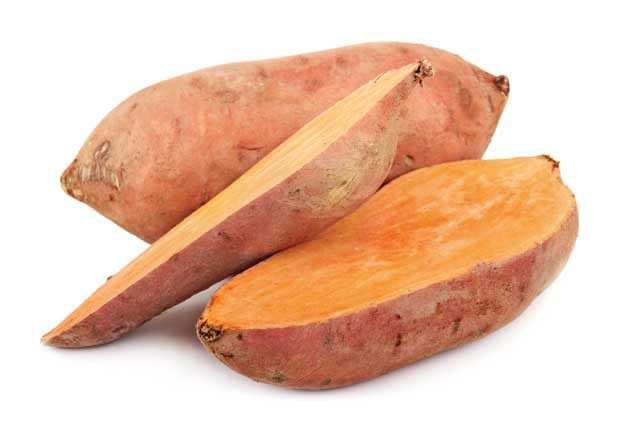

Were we aware Māori warrior Hōne Heke used our valley as a hideaway between battles with British soldiers? You know nearby Peria? Pre-colonialism, it was the most densely populated valley in New Zealand. Had we noticed that big hill past the swimming hole? It was a significant pā site. Did we realize those marbled clouds over Doubtless Bay mean it’s time to plant kūmara?

Nearly 40 per cent of the Far North’s inhabitants identify themselves as Māori, according to the 2013 Census, and while te reo Māori may seem in danger of extinction in some parts of the country, New Zealand’s other official language is widely spoken by pockets of the population around us.

Wondering what other conversations he may be privy to if he entered into te reo’s syntax and chatted with its orators, James spent the past winter’s long evenings muttering over text books and dictionaries. Thanks to night classes, immersion groups and a geeky enthusiasm for grammar, he was semi-fluent in Māori by springtime and conversing with speakers whenever he could.

An invitation to stay at a local marae followed, where our family was warmly welcomed. Among other discussions, an ethos of living in tune with the land was shared. Although our hosts lamented they’d largely lost this ability subsequent to colonisation, they were reclaiming old skills and independence by seeking to nourish themselves and the earth through organic kai cultivation.

Like them, James and I have also been at work recovering wisdom that would have been universal half a dozen generations up our genealogical lines. Our classroom is the large garden we’ve established with our neighbour and teacher, Dave. Known locally as an organic gardener extraordinaire, Dave’s been cultivating a wide variety of crops and saving the best of his seed for the past 10 years, creating genetic strains perfect for Far North conditions. Planting by the moon and walking the land in his big bare feet, his rhythms are those of a man listening deeply to the seasons.

Our community garden was sown with a promise of bounty. Filled with anticipation, I rounded up 80 agee jars but unexpected rain blackened the tomato crop with blight. A pheasant began pecking at the growing potatoes and corn. We fenced off the area containing the eggplants, capsicums and chillies, but the possums and pukekos found the watermelon vines.

As we trapped, weeded and watered, I reflected on food independence. It’s easy to be nonchalant about the processes involved in agriculture when reaping’s just a matter of selecting items from supermarket shelves, yet what would happen if modern food distribution stopped? Our ancestors must have lived pretty precariously when a failed harvest equated to winter starvation, but how resilient was I, when I hadn’t even known how to mound potatoes?

Under Dave’s tutelage, we brought in the borlotti beans. Onions were sacked. Then he announced we had half a tonne of potatoes to harvest. The kūmara would follow, he said. Thoughtfully surveying our half-finished house, James and I added a cellar to the wish list.

Meanwhile, Dave’s shed was where we learnt how to store produce. It’s the sort of intelligence I’ve come to increasingly respect. Once upon a time it would’ve been handed down through the generations; links in the chain of humanity’s survival.

As James and I increase our reliance on the land to sustain us, I’ve noted an interesting thing. Like Dave, we too, have begun listening more intently to the natural world. It speaks of a place in which we belong but certainly not at its centre.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.