How Liz Morrow created a Garden of International Significance at Omaio

As Liz Morrow sits and drinks in her environment, she sees an extraordinary place of which she is but kaitiaki — or guardian

Words: Claire McCall Photos: Tessa Chrisp

When Henry David Thoreau retreated to Walden Pond to live simply, deliberately and “suck out all the marrow of life”, he stayed two years then returned to “civilized” society an apparently enlightened man. Liz Morrow has far more stamina.

Her version of a cabin in the woods is a low-key log house tucked into a native forest where a 1500-year-old puriri and a 1000-year-old kauri, its painterly trunk towering to the sky, assert the longevity not permitted human form. Her “pond” is the stretch of ocean between the shores of the Takatu Peninsula and Kawau Island.

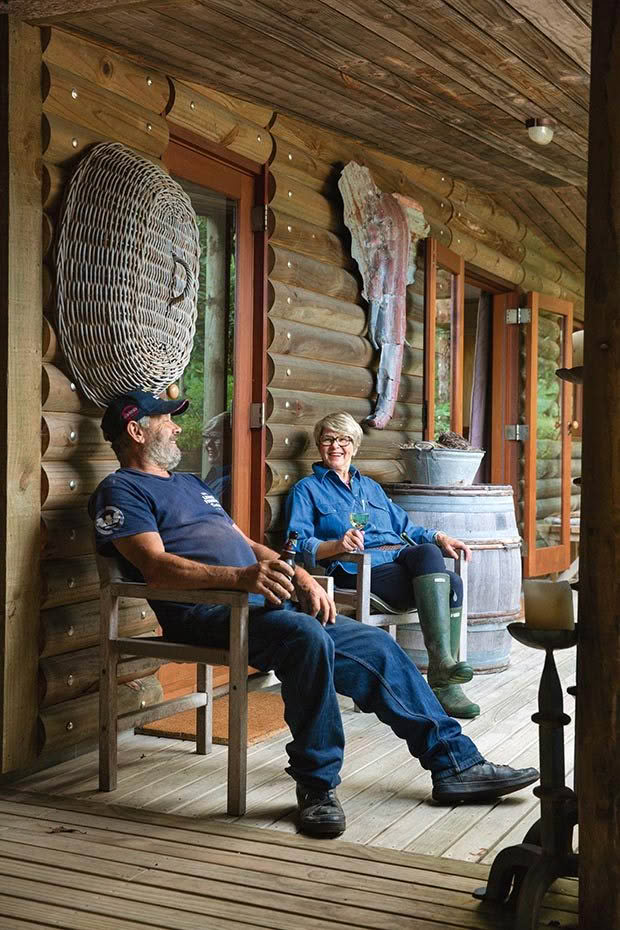

A gathering of garden lovers on “Johny’s Deck”, which opens to sweeping views of Takangaroa Island and the larger Kawau Island beyond. “We have a run-about and often go boating out in Kawau Bay,” says Liz.

Beneath the ancient canopy, Liz has, in a little more than 10 years, crafted a garden that “does not compete with nature”.

In April, Omaio was named a Garden of International Significance by the New Zealand Gardens Trust. Liz is proud of the award, and honoured, but has yet to celebrate. She has far too much to do. Unlike Thoreau, she has found her truth is spiritual doing, not spiritual being.

The dual drivers of inspiration and commitment are required to reach the pinnacle of any vocation. In this, Liz had a good start.

Growing up in Pakeho, she had an “incredible, unforgettable childhood”. Snapshots include riding her horse to school, winning first prizes at the local shows for her pikelets and scones, and admiring the yellow banksia rose that clambered over the tin shed of the long drop.

Rural life in Pakeho, a tiny community in the King Country, blessed her with the farm-girl fortitude that has allowed her to work this seven-hectare property near Matakana into a seamless melding of nature and the man-made, and keep it maintained to her exacting standards.

“My parents always said, ‘Don’t attempt a job unless you’re prepared to give 100 per cent.’”

She was – and is. At 70, she still spends six to seven hours a day outside propagating, planting, clipping, sweeping, grooming. “My children encourage me to put up my feet and admire the wallpaper,” she laughs. Not likely. “The garden is my gym and my golf course.”

In rare idle moments, Liz is far more inclined to gaze fondly at the framed kahuweka that hangs above an antique sideboard in the dining room. The cloak, woven with weka feathers from the Chatham Islands and featuring the Matariki star cluster on its lower border, was made by Dr Diggeress Te Kanawa, daughter of Dame Rangimārie Hetet, both of whom were instrumental in reviving the art of Māori weaving. It is a significant piece, but also a symbol of connection.

“My mother had a wonderful friendship with Diggeress, as did I,” Liz explains. ‘

The garden room is the latest addition to the cabin and has an outlook towards Kawau Bay.

The family farm at Pakeho (called “Koropupu”) was five kilometres from the Māori settlement of Oparure, which is how Liz’s long association with the Te Kanawas began. Diggeress named the cloak “Te Awhi” or “to embrace”, and it took two years to make. In the book room that Liz playfully dubs the “marae”, there are several examples of Hetet’s work on display.

“When I was heading off on the Oriana on my OE in 1967, I was gifted two kete woven by her. They were a talisman for safe passage.” She treasures the kete recently given to her by Hetet’s granddaughter, Kahutoi Te Kanawa.

After a hard day’s graft, Lance Michell, who helps Liz out once or twice a week, takes time for a chat and a beer. On the wall behind is a corrugated elephant by family friend and artist Jeff Thomson, along with a French food basket.

These harakeke ketes have evidently done their job well, for Liz has been gently guided by benign higher powers not only through youthful exploits in Europe, but up the right paths at the right times too. It would barely be a surprise to prick her finger and find chlorophyll coursing through her veins. Still, this green-fingered guru would have been a nurse if it wasn’t for a careers visit to the Auckland Hospital.

“As soon as I entered the children’s burns ward, I passed out,” she recalls. She swiftly segued into secretarial college.

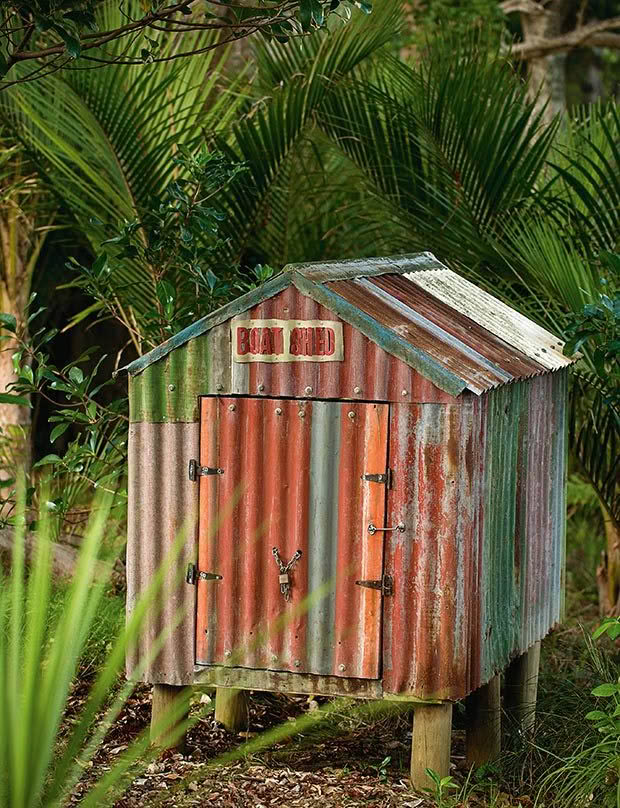

Artist Jeff Thomson made the miniature corrugated boat shed, filled with hundreds of golf balls that Liz’s son Johny likes to whack off the deck.

Aside from a mother who spoke of plants by their Latin names and encouraged her young charge to “repeat after me”, Liz has no formal training and yet has forged a life as a garden designer and creator of note.

A passion for plants and evident talent were the only requirements to ensure her a job as the first manager at Auckland’s Eden Garden. “That was a huge undertaking,” she says. She established an office, put systems in place, and made some huge improvements to the public gardens.

A concrete tub on a totara stand provides fresh water for visitors to the garden. “It’s also good for topping up your whiskey,” says Liz

Omaio, the home she and her then-husband Rod Morrow bought as a holiday escape in 1980, was destined to become her crowning achievement. In 2005, when Liz felt the need to “head for the hills”, she moved here permanently. Then she sat and drank in the environment. So began a legacy. Liz admits she could never be an artist – “I can’t draw a stick figure” – but she has an eye for proportion and balance.

A kahu weka (cloak) made by Dr Diggeress Te Kanawa from weka feathers is a focal point in Liz’s dining area.

Working with lengths of pliable garden hose, she mapped out curvaceous beds at the foot of the cabin and surrounding the tennis court. She likes to think the fluid lines reinterpret the outline of the coast, and the rounded shapes reflect the curl of the waves. It was six months before she started planting.

The perfectionism of such geometry brings a relaxed nature to the design. Curvaceous beds in the proximity of the pine cabin are filled with clipped balls of hebe, pittosporum, ilex, Metrosideros carminea and Carpodetus serratus “prostrata”, and are reinforced by spherical sculptures in corrugated iron and driftwood. Breaking the theme are the tall spikes of taiore, a variety of harakeke gifted by Dr Diggeress Te Kanawa.

A large Jack Marsden-Meyer piece made of driftwood and puriri.

Drifts of hydrangeas provide showy courtside support for the tennis tournaments Liz hosts in summer, while shade-loving clivia in butter yellow and fire orange take up the colourful cause in winter.

“Continuity is easy on the eye,” says Liz. “I’ll plant four of five hundred of one thing so there’s no interruption.”

A giant “moa” footprint leads to Jack’s sculpture; the kereru at the entrance to the garden is carved from heart dicksonia and acts as Liz’s guardian.

Ambling down the shell path of Jane’s Lane (named for Liz’s daughter) towards the koru-shaped vegetable garden, this gardener cannot help but pull out a weed or a wayward stalk of grass. She exclaims at the insect life that seems to have attacked a rengarenga and investigates an unexpected seedpod that has dropped from above.

At Johny’s Deck (named for her son, who helped create the bush walk paths and visits regularly to work on the property), a bench is placed beneath a sampler of native trees: puriri, tōtara, rimu, kauri, kowhai, nikau, kahikatea, taraire, manuka and kanuka. The outlook is towards Rabbit Island and, on a good day, the Coromandel Peninsula.

The sheltered courtyard on the north side of the cabin is an all-important, all-season space for entertaining and was developed 14 years ago, before the rest of the garden took shape.

At Omaio, a word that means peace, quiet and tranquillity, Liz enjoys many good days.

“I resent leaving,” she says. “I don’t do coffee and a week can go by when I don’t even get in the car to go down the road.”

Not that she’s a solitary figure. Ali Skinner happily lends support and Lance Michell is onsite weekly helping out with jobs such as lawn mowing and the countless tasks that keep this garden shipshape.

Kahutoi and workshop volunteer Alison Anderson join Liz for snacks and sundowners. An ornamental grape clambers over the stone wall of the fireplace.

Then there are regular games of bridge and mah-jong and an endless stream of visitors from far and wide who come to view this special corner of the world.

Her two grandchildren, Jett (4) and Halo (16 months), also like to take “Grandie” for a spin on the garden swing, or order in her famous orange muffins to their treehouse for afternoon tea.

A walkway behind the house near the outdoor shower leads through a bed of bergenia “Snowmound” beneath a kanuka tree where a kererũ chick waits for its once-a-day feed.

Spherical forms are repeated throughout the garden. Teak orbs on the lawn are backed by the rounded clipped shapes of pittosporum “golfball”, Raphiolepsis fergusonii, Teucrium and ficus “tuffy” among others.

“It’s lovely to think that they don’t feel threatened here, even so close to the cabin.”

Liz thinks of Omaio in terms of kaitiakitanga, saying she considers herself a steward of the land. But to anyone who sees her in her element, her oversight is obvious. This relationship is a two-way street.

She is its guardian – and it hers.

HARMONY IN THE GARDEN

Liz believes creating harmony between plant types is important.

“Plant choices need careful consideration to ensure they fit the locality and marry well with plant material already established.” Three examples of this include:

➊ Kiokio is encouraged throughout the garden. “It grows naturally in the bush areas so we have continuity of the same plant in exposed and sheltered sites.”

➋ The bold leaves of Ligularia reniformis (tractor seat plant) contrast well with native carex. It’s a happy juxtaposition of textures.

➌The clivia collection growing under the canopy of kanuka and manuka contrasts with the large leaves of bergenia “snowmound”, which form the front of the clivia border. Naturally occurring ground-cover ferns and grasses soften the blend.

WEAVING WORKSHOPS

At the inaugural Creative Matakana event held in May, Liz Morrow organized for family friend Kahutoi Te Kanawa to host a five-day harakeke weaving workshop. Eleven participants learned the techniques of harvest, preparation of the plant material and plaiting techniques to craft a kono (food basket) and kete (basket).

Kahutoi, who is completing her PhD on the intergenerational transfer of weaving knowledge, says:

“Harakeke weaving is one of the principle practises of Maori which employs the resources of nature for purposeful use and, in pre-European times, was integral to survival.

“It is a way to hold onto our culture and language through the knowledge imbued in the work and the stories that come through it (during the communal process

of weaving).

“Raranga should be integral to the school curriculum as it teaches about working with natural elements (science). There’s maths involved, visual language, communication and art.”

✬ There are more than 200 varieties of native harakeke.

✬ Captain Cook called the plants “flax” because it was reminiscent of the flax linen plant.

✬ The dates for the next Creative Matakana event are 7–11 May, 2017.

- Traditional Maori weaving

- Kahutoi Te Kanawa gathers the raw material for her harakeke weaving workshops.

- Participants learned the techniques of harvest, preparation of the plant material and plaiting techniques to craft a kono (food basket) and kete (basket).

- Lizz preparing for the harakeke weaving workshop.

- Kahutoi is the daughter of master weaver Dr Diggeress Te Kanawa and granddaughter of Dame Rangimarie Hetet, also a tohunga raranga.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.