Polly’s Blog: Pondering parenting styles

Polly tests an alternative parenting method on for size.

Up until this winter, our family’s indoor life has predominately taken place in The Room. This was the first section of our house to be built, and for a couple of years, the only indoor space that existed. A kitchen and bathroom followed, but The Room was where we have eaten, slept, socialised and gone quietly crazy during rainy days of confinement with our two young children.

Vita and Zen in The Room.

At night, as the children slept up above on the mezzanine floor, The Room was where James and I had our grown-up time. Because the kids are light sleepers, we became masters of whispering; racking up thousands of hours of hush-toned conversations since we came here. In the golden glow of candle-light, our gentle murmurs could seem romantic, but out of necessity, James and I have had plenty of whispered arguments too. An angry whisper is known in our family as a hissper, and it is extraordinary how much scathing, and fury one can load into such soft undertones.

This winter, however, the hissper has been gasping its last. Not only have we now shifted into our new lounge where James and I can talk at normal decibels each night; but we’ve also just completed a communication course that’s dramatically reduced our arguing time.

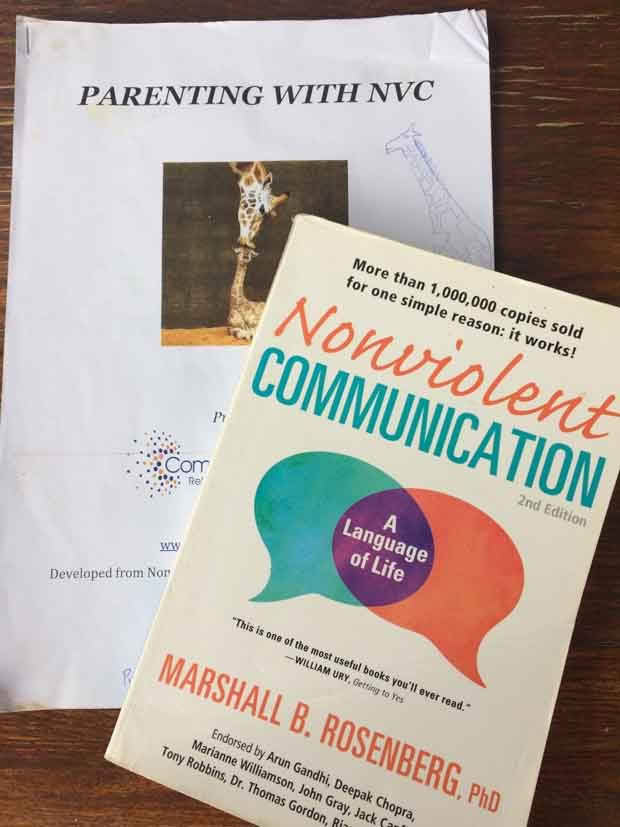

We signed up for the six-week ‘Parenting With NVC’ course without knowing a thing about it. Our five-year-old’s iron will, and our two-year-old’s predilection for ‘no’ were motivating factors, but it is also rare that any sort, of course, is offered in our part of the woods and one must carpe diem when one can.

To be honest, forays into parenting theories and models had left me disheartened and confused. Not long after Vita was born, a friend sent a child-rearing book she claimed had revolutionised her approach to motherhood. Beguiled by the soft yellow cover, I opened its pages and was dismayed by how many errors I’d already made in my daughter’s short life.

Tickling a baby was a form of assault. To pick an infant up from behind was to objectify it. Doing anything to a newborn without first explaining your action was a failure to acknowledge its intelligence, while baby-talk was both disrespectful and patronising. Glumly I surveyed my sleeping child, wondering at the damage done.

This was my introduction to the literary genre of parenting. Up until Vita’s arrival, I’d thought parenting was simply a verb for getting on with the job. Babies cried, and you soothed. They hungered, and you fed; they needed care, and you gave it. So long as there was love, it hadn’t occurred to me that there were right and wrong ways to nurture.

Zen acting up in the playground.

The books that followed, gifted by well-meaning people, showed how mistaken I’d been. Presumably penned by equally well-intended authors, they were sombre warnings. Not only were there errors to be made as one set about raising a child, but the consequences of those blunders could permanently impede their chance of a happy emotional life. After all, the formative years are the most important in your child’s whole life.

The problem was that they couldn’t agree on an approach. Some were in favour of the naughty chair and a jolly good growling, while others said a child should never be isolated, threatened or humiliated. Be firm with discipline, a collective of authors advocated, while other books stated this produced fear-bound kids who went on to become obsequious, submissive adults.

One particularly smarmy author, who believed children should never be shouted at, detailed a day her two-year-old had filled a wall of her house with crayon scribbles. ‘This was an opportunity for us to bond as we spent a delightful afternoon scrubbing the wall clean together,’ she wrote. Unfortunately for my son, there was nothing delightful about my attitude when he drew with biro all over our new wooden stairs. Guilt had followed my anger.

As it turns out, Nonviolent Communication (NVC) is a four-step process of relating to ourselves and others through an awareness of feelings and needs. Rather than approaching a child or partner with judgments, labels, punishment or blame, it offers techniques for adopting empathy, curiosity and compassion for the other instead.

At first, we were a little dubious. Since entering into the Far North parenting milieu, James and I have been privy to a style of child-rearing branded as Freedom Parenting, where no boundaries, consequences or expectations seem to exist. To these mums and dads, discipline

is a dirty word, manners are antiquated, and any wild, anti-social behaviour is viewed as proof of the child’s free-spirit. These children do not make good guests.

‘NVC is definitely not a form or permissive parenting,’ our instructor assured us. Instead, it’s a way of listening to what’s really being said, and hearing the needs behind whatever anyone says or does.

Even before we started learning the technique, the course was heart-warming just to hear everyone sharing their parenting woes.

‘I hear myself turning into my father,’ a man despaired.

‘How do I get my children to like each other?’ someone else wailed.

‘There’s no cooperation. Ever,’ a woman said, close to tears.

Through role plays, games, exercises and discussions, the four steps of NVC were presented: Share your observation of a behaviour, say how you feel, identify your needs and then make your request. To an uncooperative child, it might go like this: ‘When I see you sitting on the bed when I’ve asked you to get dressed, I feel upset and tired, and I’m needing cooperation. Would you be willing to put your clothes on?

To my surprise, it works. As a beginner, I am clunky and formal in my approach, but something about the way it is worded and shared keeps the other side listening and open. Even with Zen to whom numerous requests/orders/snarls to let go of my legs while I’m cooking go unheeded, a dialogue of ‘when I see you continuing to grasp my ankles when I’m making dinner, I feel angry and frustrated. I need ease. Would you be willing to let my legs go?’ has been met with a two-year-old grin as he’s moved away.

Of course, children aren’t robots and don’t always leap to consent when I voice what I want, but the course has offered tools for dealing with conflict harmoniously, rather than punitively, and our children seem a whole lot nicer to live with than when we began. Vita reckons James and I have improved as well.

Certainly our old technique of fighting fire with fire has gone.

‘Shall we NVC it?’ one of us will say as soon as we’re no longer on common ground and before long, we’re back at a space of mutual understanding. The hissper can rest in peace.