Waikato farm diversified with Nikau cave business

Looking for opportunities to keep their adult children working and raising their families nearby, Philip and Anne Woodward added cave exploration and a café to their farming operation in a remote area south of Port Waikato

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Mark Smith

Beautiful limestone country spreads south from the mouth of the Waikato River, hugging the solitary coast where the Tasman Sea toils daily against the black-sand beaches. Between Port Waikato and Raglan nikau, cabbage trees, kowhai and puriri creep out of sheltered hollows between the lush grass and ribbed limestone outcrops, providing tui and kingfishers with excellent lifestyle opportunities.

Their human mates are not able to choose from so plentiful an array of options. Towns are scarce. Settlements are sparse. Catherine Tafto (née Woodward) grew up here with her four siblings and parents Anne and Philip in an area known as Waikaretu.

The Woodwards think of it as relatively central (one hour 30 minutes to Queen Street) yet, as Catherine learned recently when planning her imminent second birth, Waikaretu is officially, obstetrically speaking, “remote”.

- Anne Woodward in the cafe herb garden.

- Visitors Lucy and Jack Smith

- Team member Jana Beer

- Mattias in front of the office which is enclosed in a wool press from the farm’s woolshed.

- The cave exits into the green of the bush.

- Small visitor Jack on the swing-bridge which leads to the reserve.

The primary school is small but has a big local spirit. And nowhere is the soul of this limestone country more evident than at the Nikau Cave and Café where multitudinous members of the Woodward family, including their many foreign “family adoptions”, are busy going about their varied businesses.

Philip Woodward was born here; his father returned from World War II and took up a “rehab” farm. Philip and his two brothers went for it as commercial shearers (internationally competitive shearers at that), shearing their way into farm ownership.

Originally the three brothers farmed their land as one property then, as they married, it was broken up. The block Philip and Anne ended up with was leasehold land and not available to freehold. Subsequently they bought 237 hectares – what they could afford but not enough to support their five children if they all wanted to stay on the farm.

“I wanted them to have the choice of coming home and working with us but there is no compulsion to do it,” Anne tells NZ Life & Leisure on the eve of her departure for Nova Scotia to be granny for a month to the three-month-old child of their eldest son, James.

Anne makes coffee at the café’s macrocarpa-slab counter.

“The farm just wasn’t going to offer that opportunity so we began looking for other things we could do which might offer the kids a chance to stay in the district. Then, about 15 years ago, after one farming crisis too many, we really started thinking hard about diversifying.”

They’d long known that beneath the craggy limestone in a gully filling with regenerating native bush was an extensive cave system which, with its proximity to the country’s most renowned cave at Waitomo, might offer tourist potential. Nikau Cave, according to the positive comments from previous cavers in the café visitors’ book, is as good as if not better than Waitomo, with stalagmites and stalactites to rival.

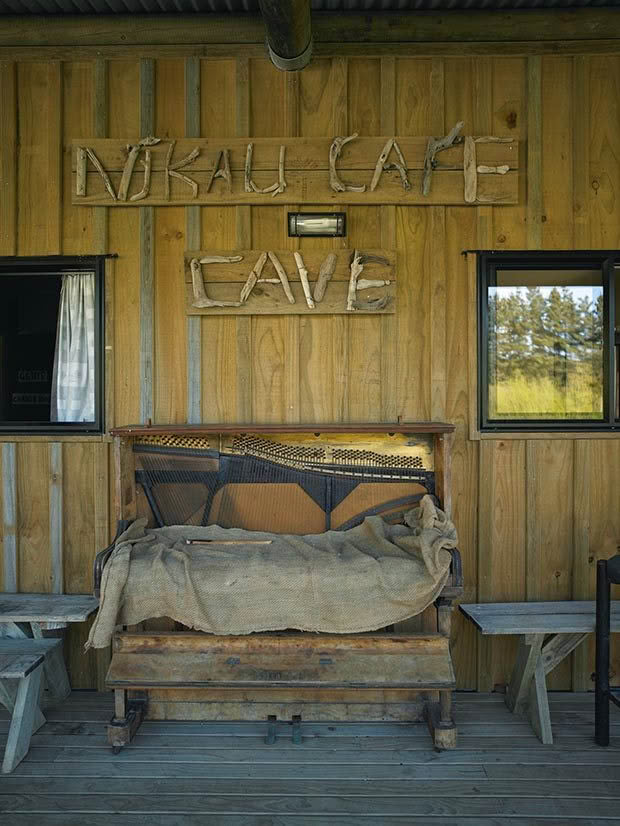

An old piano makes an unusual seat.

For the past 15 or so years, caving had taken a portion of the Woodward family energy while their farming enterprise took the rest. Still, Anne and Philip knew that they needed to “crank up the caving” to meet their goal of offering all the children an opportunity to come home to work. They also realized that without better marketing to drive more visitors to the cave the venture would never reach its potential.

So Anne and Philip began looking for a piece of land on which they could establish a café to draw in the traffic and send more visitors underground.

Blackberry Island, a triangular-shaped piece of land bounded by a river on three sides and near the cave entrance, was ideal in every way and plans for the café began to take shape.

While Anne could see in her mind’s eye the rustic café crafted from Mrs Fox’s macrocarpa (Mrs Fox was an elderly neighbour about to mill her old trees) with cathedral windows lifting guests’ eyes to the hills to admire the magnificent limestone outcrops towering above the site, could the bank see it?

“It took the bank a very long time to say no, they couldn’t see it working and to be fair we already had a big mortgage.”

Jana and Catherine have assistance from Mattias and Addison at a planning meeting.

So certain were the Woodwards that their café would succeed they regrouped and put the proposal to another bank. Could the second bank see a busy café, a car park jammed to the verges, vegetables bursting out of the gardens?

No, the second bank saw an isolated site and inexperienced operators. And it took them a very long time even to see that and then say no.

Anne knew that there was enough traffic on the road, despite its isolation, for the café to work so they approached another bank with an even tighter business plan.

After a long time, yet again, the third bank admitted they couldn’t see it either and turned them down.

It was a big disappointment but a spur-of-the-moment visit to a floristry extravaganza in Hamilton had a fortuitous outcome.

A programme advertisement for the Southland Building Society suggested it would support such an enterprise and the café dream finally became a booming reality.

“We were blown away by what happened; it must have been word of mouth and maybe that was because the building was quite unusual and everyone could see it from the road, so they all talked about it,” says Anne.

The Waikaretu Stream runs through the QEII reserve next to the café.

Philip says she’s just being modest and that it is her extremely good food that made the café grow so rapidly.

Whatever, they’ve captured more than the Sunday drivers who loop round past Port Waikato looking for weekend caffeine. Locals come on Friday nights for pizza; on spinning days there are few fireside seats left between the knitters and the spinners, some of whom teach café casuals to spin over their lattes. So here’s the café offering Anne work and the caves keeping Philip busy underground although he describes himself, ironically, as “a man of leisure who swans around and occasionally makes coffee”. What about the wider family?

It is a bit hard to get a handle on this family which, thanks to the international shearing connections which Philip describes as “like convolvulus”, is just as likely to hop a plane to Europe or North America (particularly Nova Scotia) as it is to travel to Hamilton.

The interior of the cave rivals Waitomo’s best.

Philip, a former international title-holder, spent six weeks last year shearing in the islands off the coast of Nova Scotia to earn enough money for Anne to go there to spend time with her newest grandchild. (Philip loved getting around the seven islands the contract covered which involved loading up a dinghy with generator and gear, then anchoring off and rowing ashore.)

Emily, the second of the enterprising Woodward clan, took up competitive shearing after she’d finished her Bachelor of Agricultural Science at Massey University. She was sporty and after her father taught her to shear she found it became quite addictive, especially once she started competitive shearing. So proficient did she become that she challenged and successfully broke the women’s world record for lamb shearing.

Inside the largest cavern.

These days Emily runs a commercial shearing gang with husband Sam Welch whom she met at shearing competitions; he comes from a farming family in Dannevirke and she competed against and beat him – just once.

She also owns and runs a Coopworth stud in conjunction with “Canadian Kate” – yet another member of the extended Woodward clan – who is currently applying for citizenship. (Coopworth is a maternal breed, says Emily, valuable for increasing lambing percentages.)

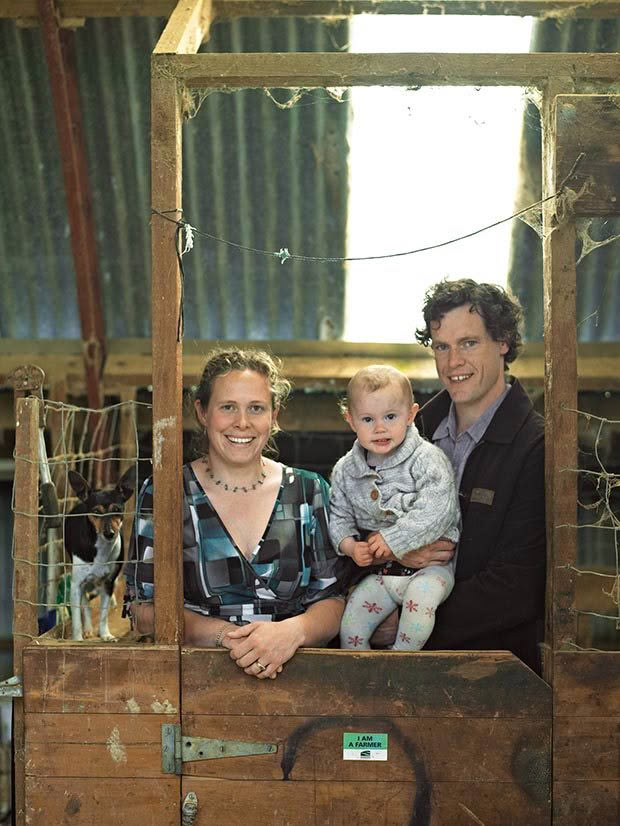

Catherine and her husband Frode Tafto (a Norwegian whom she met while studying for her International Communication degree at Unitec) also live nearby with Catherine taking a firm hand with day-to-day care of the family’s pair of toddlers (her 20-month-old son Mattias and Emily’s 18-month-old daughter Addison) as well as keeping an eye on the marketing of Nikau Cave and Café.

The Welch family: Pia the miniature foxy, Emily, Addison and Sam.

Non-resident family members, James in Nova Scotia, Andrew at teachers’ college in Thames and Nicola nursing in Auckland, all harbour dreams of coming home. Even on short visits, they can throw on an apron and – in Andrew’s case – show expertise in the café kitchen. “It is at times like those,” says Anne, “when most of our kids are here and the café is humming and Philip is working behind the bar and we’re all doing various jobs, that we purr the most.”

This article was first published in Issue 36, March/April 2011

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.