Family of five living large in a 20sqm off-grid tiny house

- Shelving by their bunks gives them room to store their books and toys. Under the bottom bunk, boxes and baskets provide more storage.

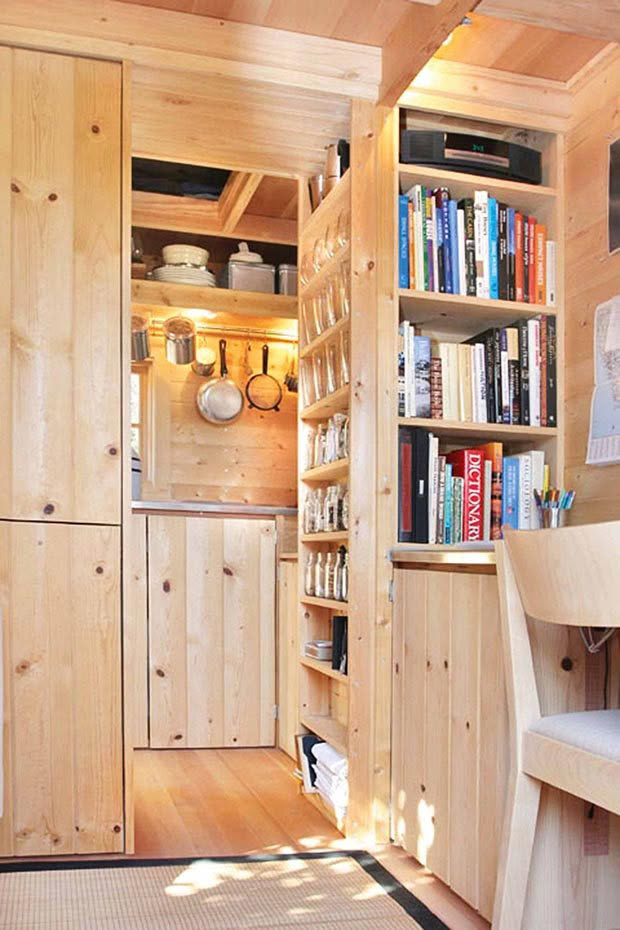

- We built the timber pantry to maximise storage in this corner.

- This corner of the bedroom is dedicated to storage: tightly-packed chests of drawers, with shelves above and hooks for the kids’ bags. Each family member has one chest of drawers for clothes, and we go through them monthly, ruthlessly removing what we no longer wear.

- The cedar doors were $1.50 on Trade Me, and the handles are cut from gnarled manuka tree branches.

- A good outdoor play area really helps when you have children in a tiny house. Our kids have swings, a slide, a seesaw, a tramp, a sandpit and a playhouse. Whenever it’s not raining- and sometimes even when it is- they get told to go outside and play!

- The bounty from our garden, which feeds us, and provides income.

- We run a small scale market garden called Little Creek Farm.

- Home grown carrots.

This family of five lives in a 20m², off-grid and smart phone-free home with a composting toilet and a shower they share with the sky.

Words & Images: Melanie Brookes

Who: Melanie and Ben Briookes, Pippa (7), Kit (5), Sylvie (2).

Where: Awaawaroa Eco Village, Waiheke Island

Website: www.awaawaroa.org

“You’ll get cabin fever.” “You won’t get any sleep.” “You won’t make it.” That was what we heard in 2013 when we announced to family and friends that we were running away from suburbia and moving to a tiny, off-the-grid cabin with an outdoor bathroom in an eco village on Waiheke Island.

Their reactions were, shall we say, mixed. The comment that we wouldn’t make it was from my wonderful mum, who was seriously worried that her grandchildren were being whisked away to the 19th century.

Three years on, we’re still living in the tiny cabin, and we’re still making it. Our home is within the Awaawaroa Eco Village where we share, along with 14 other families, close to 160ha (400 acres) of land, a mixture of bush and pasture which curves around the shore of Awaawaroa Bay, at the southern end of Waiheke.

The Brookes family (L-R): Kit, Ben, Mel, Sylvie, Pippa

Our little house is 20 square metres. Yes, 20. That’s not a typo. The average New Zealand house is about 150 square metres, so you could fit our house into the average home seven times, with room to spare. We didn’t set out to live in a tiny house. When we bought one of the 15 shares in the village, the cabin was already on our land, a gingerbread cottage sitting in a jungle of kikuyu grass.

The macrocarpa kitchen has cupboards, shelves and hooks to avoid cluttering up the tiny benchtop. Even so, only one of us can work in the kitchen at a time, otherwise we end up quite literally stepping on each other.

The cabin is built entirely out of natural materials. It has macrocarpa cladding, pine and redwood lining, and recycled native timber floors and joinery. It’s split into two rooms. There’s a lounge-kitchen-dining room where pretty much all our living happens, and a bedroom, where all five of us sleep. The bathroom is outside, with a composting toilet and outdoor shower.

We run a small scale market garden we call Little Creek Farm on our patch of land. There’s a diverse range of vegetables – around 20 different types – with the aim of feeding island families. We sell our produce through a weekly vege box scheme, and at the local market.

The ‘master bedroom’ is tucked up on a mezzanine in the main bedroom and accessed by a ladder, with just enough room for a queen bed. From the bed we can watch all three of our children sleeping which is lovely when they’re asleep (not so lovely when they’re not).

We’re entirely off the grid. Solar panels provide our power, enough to run a fridge, washing machine, laptop and lights, but not a lot else. Heating comes from a little potbelly stove and water is courtesy of the sky. No smart phones. On a good day, it’s all very Little House on the Prairie, but with running hot water and broadband. On a bad day, with three kids bouncing off the walls and two parents shouting to be heard over the rain pounding on the roof, it’s more like a form of torture. Only self-inflicted.

I exaggerate, but there are definitely challenges to living in a tiny house, especially with children. Rainy days are tough. When we’re crowded into two small rooms, we do sometimes (quite literally) trip over each other. Small children can make a fair bit of noise and chaos at the best of times, but in a tiny space it all seems somehow… magnified.

It can also be hard to find private space. Time out needs to be either outside, or tucked up on one of the beds. The two older children have ‘bedroom space’ in their bunks, and they each have a set of shelves for their special things so they have an area to call their own.

Accommodating visitors is trickier. The dining table seats only five and even if it was extendable, there wouldn’t be any space for it to extend into. Bed space is even more of a challenge. We now have a cute little 1.5-seater couch that pulls out into a small single bed. Before then, when my mum came to stay she sometimes slept under the dining room table as it was the only floor space big enough for a mattress. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not complaining. We expected all this. Heck, we moved into a house that allowed just four square metres per member of the family. We knew there would be some difficulties.

What we didn’t expect was the surprising number of benefits, the positives of living in a tiny house that have changed our outlook on housing, on family, and even basic human ‘needs’. From a practical point of view, a small house is quicker to heat and quicker to clean. I can clean all the windows in an hour or so, and cleaning all the inside surfaces doesn’t take much longer. Not that I do these things on a daily basis or anything. Just that if I did, it wouldn’t take too long. Hey, I have three small children: clean the windows and 10 minutes later there are peanut-buttery fingerprints at toddler height. It’s an exercise in futility.

Some of the benefits have been more abstract. We’ve learned to make do and to go without. When you’ve got less space, you have less stuff. As parents, it has been a great excuse not to buy unnecessary toys for our kids. “I’m sorry sweetheart, we can’t get that life-size electronic dinosaur/2-metre-tall stuffed pink teddy/other piece of plastic rubbish – we just don’t have room.” As a result, we’ve watched our kids play again and again with the same basic toys, inventing new games with the playthings that have been entertaining kids for decades: Lego, puzzles, books, wooden trainsets, miniature animals, toys that give a lot of joy for the space they require.

It’s not just our kids who’ve had to shed belongings either. Living in a tiny house means you re-examine nearly every single possession, asking: ‘Do I really need this?’ We buy new clothes only when the old ones wear out as there’s just no more room in the drawers. The other day I went through our cutlery collection, deleting from our stock two knives, two forks and three soup spoons. This is perhaps taking minimalism to an extreme, I admit, but every millimetre counts.

Perhaps the greatest thing about living in a tiny house has been its effects on our closeness as a family. I mean, obviously we’re quite literally ‘close’ but I think it goes deeper than that. The kids are learning to get along in a small space, and the same goes for Ben and me too. None of us can just disappear to our bedroom, slam the door and sulk. We’ve got to work it out. It’s not always easy, but it probably makes for a stronger family unit in the long run. I’m sure that one day, we’ll look back on these years fondly.

For our family, a tiny home has taught us much. We could probably manage to live in it forever – plenty of people in the world live with far less – but no doubt it will get harder as our kids get older and demand more privacy and space. That’s why we’re building a mudbrick house for our growing family, just up the hill from our little cabin. It’s a slow process – glacial might be a better adjective – as we’re doing most of the work ourselves. At around 100 square metres of floor space, it’s no mansion, less than half the size of the typical new NZ home. But, from our new tiny perspective, it’s five times the size of what we’re currently living in. To us, it’s going to be a palace.

THERE’S NEVER BEEN A BETTER TIME TO GO TINY

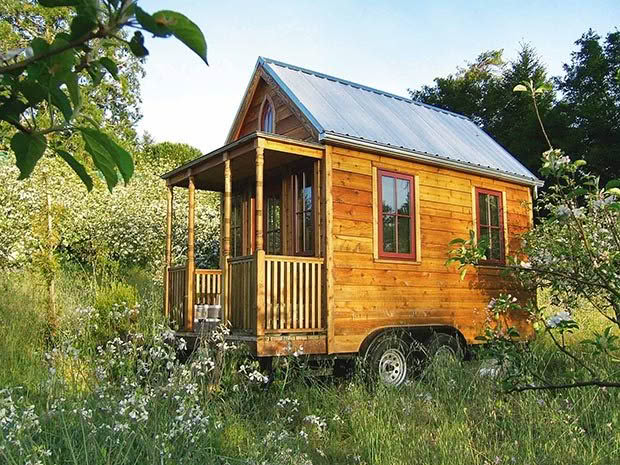

This tiny house includes a porch, bathroom, kitchen and an upstairs loft for sleeping in a space measuring 2.4m wide by 4.6m. Photo: Tumbleweed Tiny House Company.

What was once the domain of just a few hippies living in rundown caravans scattered across the country is now a genuine movement. Google ‘Tiny House New Zealand’ and you’ll get pages and pages of hits, from Facebook pages set up to connect people who are interested in tiny house living, to building companies whose sole focus is tiny houses.

You’ve probably noticed house prices are increasing. In 2016, the average New Zealand house price passed the half-million-dollar mark, and if you’re wanting to build a new home, it’s a standard cost of $2500 per square metre.

Photo: Tumbleweed Tiny House Company.

It follows that a smaller house will cost less, and tiny houses are less costly for the planet too, using fewer materials, and creating less pollution and rubbish in the process. A 2006 study for North Shore and Waitakere City Councils estimated that the building and demolition industries contributed around 50% of the total waste stream in New Zealand, so the choices you make regarding your home – the materials it’s made from and, above all, its size – are incredibly important.

This is the 8.2m² home on wheels that was the first home for US builder Jay Shafer. He now runs the Tumbleweed Tiny House Company, which specialises in mobile tiny homes and recreational vehicles. Photo: Tumbleweed Tiny House Company.

One of the reasons the construction industry has such a huge environmental impact is that houses are getting bigger and bigger. If you built an average-sized new house in the 1950s, your home would have been about 117m². These days, you’d be building more than 205m². The trend shows no signs of slowing down. While houses have been swelling by an extra 75%, the families in those houses have actually been shrinking, with the average New Zealand household now numbering one less person than in the 1950s.

It makes sense for practical, environmental and economic reasons to minimize your house size. Not everyone wants to live in 20m², and some days I’m not sure if even I’d recommend it, but tiny houses have valuable lessons for most of us.

Photo: Tumbleweed Tiny House Company.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

MORE STORIES LIKE THIS

How this small country school is turning a profit from the land

Doing the locomotion: railway carriages converted into cosy home

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.