Architect’s dream home built from coolstore panels

When this pair took flight from Kapiti Coast’s cold climate for a warmer north, they’d wanted to migrate in a flock. But they’ve landed alone on the shores of the Kaipara.

Words: Kate Coughlan

Photos: Tessa Chrisp

The build required a lot of mathematics. Each wing frames a slightly different view of the Kaipara and the kowhai/totara forest.

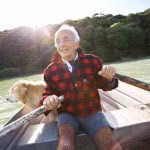

Dave Launder and Isobel Gabites (architect and author/naturalist respectively) shared a dream with like-minded similar aged friends. “It was a wonderful vision. We’d buy land on the coast, build our own houses, eat our own vegetables and live communally. We’d grow old by the sea. We’d have a dinghy to drag out and grab a feed and, when we started to get a bit rickety, we’d hire a nurse to look after us.”

So here are Dave and Isobel living on the seashore in a house Dave built, growing their own vegetables and there’s a dinghy tucked under the old karaka tree by the water’s edge. Neither is yet rickety so there’s no need for a nurse. But where are their friends?

“Yes, exactly,” says Dave “we came here but none of them did.” Oh well, best laid plans and all that… this semi- nomadic couple have put down roots in Northland’s fertile soil and are enjoying the climate.

“We looked all over Northland, at dozens of properties, and we seem to be going further and further away from anywhere in our moves. The last move was up the Kapiti Coast to a property inland from Otaki. Now we are up the Kaipara,” says Dave whose love of the warmth drove that difficult departure from Otaki.

The collection of Polynesian kites was assembled on the couple’s many sailing voyages throughout the Pacific Islands. The little sailing boat named Kapiti, was made by Isobel’s grandfather for his wee boys to sail on local ponds.

Oddly enough, former mountaineer Dave, whose happiest days have been spent in mountain huts or snow caves, now hates the cold. Isobel is no stranger to a bit of chill herself. She’s one of a select few New Zealanders to have had a glacier named after them. In her palaeontologist days, she spent several years researching the planet’s longest, straightest river, which happens to be in the Antarctic and 200 million years old. Some years later she unexpectedly received a letter from the Geographic Board announcing the naming of Gabites Glacier, which lies close to one of her fieldwork areas. She was, and still is, ridiculously proud even if, she says, it’s only a small glacier.

The white lounge suite was designed by Dave and manufactured by then-neighbours in Otaki.

“We don’t feel at home here yet – that’ll take another few years. Ten years is the longest we have stayed anywhere and it takes a while to settle into a community. So leaving our last home was the biggest wrench ever.”

That home, designed and built by Dave and known as the Kaitawa House, won many architectural awards including the Institute of Architects Supreme Award 2007 and was a wonderful house to live in. But it wasn’t in the right place. The new property, part of Takahoa Farm Park isn’t exactly perfect either because Dave, though originally a Taranaki boy from the black sand beach at Opunake, prefers the white sands of the east coast beaches. Isobel, on the other hand, is in a naturalist’s heaven.

She loves the boggy tidal inlet with God’s own symphony of snapping shrimp, jumping fish and calling birds playing to her at night. She sits in her little writer’s cabin – just above the mangroves – windows flung wide, listening to it all.

“It’s amazing and noisy. There’s always something happening. Fish splashing, birds crashing into their nests and calling to each other…”

Dave set about designing a house that would sit above and on the land. He doesn’t approve of houses that are cut into the land, scarring it and imposing upon it. There’s quite a lot Dave doesn’t approve of when it comes to architecture and building, and that includes almost all of the Building Code and practically every regulation governing the design and building of our dwellings.

The house’s vertical panels, flashing a joyous blue, are a nod in the direction of the kotare, or kingfisher, after which their house is named.

“The Building Act is an ass. It starts with the explanation that its purpose is to ensure good buildings and innovation then it sets out the need to comply with the Building Code, which is a prescriptive document. So there’s already a problem. If you don’t want to do what they say is okay by the rules then you have to prove that what you want to do is at least as good. And there is no way to prove something without building it. It’s ludicrous.”

Consequently, Dave began building before he had consent (although he waited for council approval for the obligatory 20-day period in which the authority is supposed to respond to lodged drawings). He says the inspectors’ knowledge is pointless in the building process today as they are not allowed to make any comment on anything.

“Previously, you could front up with innovative ideas and the building inspectors would say, ‘let’s discuss it’. Now they’re not allowed to give an opinion and architects are not trusted to know what they’re doing.”

Dave takes a leaf from the book of his old mate, colleague and friend, the late Sir Ian Athfield.

“Ath always said it’s a whole lot harder for the inspectors to make you pull something down than to stop you building it in the first place.”

It was almost a full-time job looking for a property in Northland before Dave and Isobel settled on 1.5 hectares of kowhai and totara-edged land overlooking the Kaipara Harbour. They love living with the ebb and flow of the tide as it finds its way many kilometres up the estuary from the ocean.

So, as it stands currently, Dave and Isobel’s house is consented but not finally code compliant and that’s just to do with deck balustrades.

“It just doesn’t make sense. I can sail the ocean in my yacht (a 47-foot Moody called Moody Blue) with just a few wire railings between me and the sea but once I’m on land I apparently lose all ability to be responsible for myself and others. We told our six-year old grandson to be wary of the balcony, then saw him leap off it. By the end of the morning he was taking long runs though the living room to leap off the highest part at maximum speed.

“All aspects of risk have been over-emphasized. It’s lunacy. At our previous property we had a deck we didn’t want to fence off with balustrading so we separated it slightly from the house and called it an abstract garden sculpture. You can play silly games with the Building Code because it is stupid legislation. To avoid having balustrades we could call this balcony an observation deck for birds on the water and it would probably get agreement under the irrelevant rules made up by silly minions.

“I think there’s a lack of skills now in the compliance industry – a lack of people who actually know what will work and what won’t. Architects and engineers have become formulaic subcontractors. Bean counters are running things now and we architects are looked on more and more as mere decorators of buildings or elitist designers to the rich. Yes, there is some really good work being done, but our role should be far more focussed on leadership.

The only right angles in Kotare House are between the walls and the floor. Even the roofs of the three “funnels” change pitch from one end to the other.

“This house has very much been a hands-on build. I’ve always had the philosophy that I should never design anything I can’t build myself. I like simple design and that handmade feel that comes with it, paring things right back to what they simply need to be.”

Dave had done a conversion of a large shed on a chicken farm that was built of cool-store panels. He converted it into a small home (that was to be temporary but was so good it became permanent) and during that project he learned a lot about the versatility and attractiveness of cool-store panels. Cool-store panels come in set widths, with steel framing and an already-finished shiny surface.

“Because we built using cool-store panels, interlocking on a steel frame, it was very quick to get the roof up. It proved to be an excellent material to build in as it is insulated, rigid, malleable and able to be cut easily (though noisily) into any length on site.”

Dave and Isobel’s aesthetic rebelled at leaving the exterior as a shiny white surface so the three interlocking buildings are clad in black-stained cedar, which is weathering nicely.

Isobel has a favourite corner of the house and often hangs in her swing chair keeping a careful eye on the 13 royal spoonbills that frequent Takahoa Bay.

The first building to be completed (while Dave and Isobel lived alternatively in the new garage or on Moody Blue moored in the Hauraki Basin) was Isobel’s writing studio. From this perfectly perched hideaway, Isobel absorbs the sounds of the estuary while discharging many duties, including writing way-finding strategies for locations as diverse as Middlemore Hospital, the Auckland War Museum and Papua New Guinea’s Port Moresby stadia, as well as information panels for visitor centres round the country.

She also writes fiction (despite majoring in science at Victoria University, she was one of the first intakes to Bill Manhire’s creative writing course). She’s won the Royal Society of NZ Manhire Prize for science writing and she has published three books, The Native Garden, Roots of Fire and, most recently, The Coastal Garden.

While Isobel is perfectly happy in her spacious writing room, Dave isn’t so sure he’s not made the house too big. “I like tight spaces – yacht cabins, tramping huts, snow caves… these are some of the spaces I’ve felt most comfortable in”. But despite a few grumbles about the lack of white sand and the ongoing tussles with the compliance issues, Dave enjoyed building the house – in a masochistic way.

“Every day I learned something new and we were fairly relaxed about things. I especially enjoyed the Friday afternoon fishing trips.”

What does it all cost?

Land: 1.5 hectares

Price: $130,000 in 2012 (some sites were originally $500,000 asking price but dropped markedly before beginning to rise again).

House: 160 square metres, excluding the decks and Isobel’s writing studio.

Cost: $500,000, excluding Dave’s hours.

Design: Three “fingers” of building pointing to the sea, sitting lightly on the land not cut into it.

Construction: Cool-store panels on steel frames with cedar cladding.

Where: Eight kilometres west of Kaiwaka on the Kaipara Harbour.

Why build in coolstore panels? They are: Rigid, insulated, weather-tight, cheap, malleable, versatile, New Zealand-made, 1.2-metres wide and as long as a truck can carry.

What is Takahoa Farm Park?

The 227-hectare property is in communal ownership, except for the 50 individually titled waterside sections of about one to three hectares in size. There are 10 permanent residents and many more “weekenders”. The farm portion is leased to a local farmer who is also the farm park manager. Pest control and eradication is the responsibility all owners. Bush remnants and the hilltop pa site are covenanted. Communal facilities include a tennis court, boat ramp, fresh water lake (wildlife refuge), firewood wood lot, olive grove, trails and picnic sites.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.