9 tips for starting a local food co-op

For more than 25 years, the locals of a small rural Southland community have co-operated to provide themselves with mostly locally-grown, organic food.

Words and photos: Diana Noonan

Southland’s Riverton Organic Food Co-op enjoys a prominent position in its small town’s busy main street.

But it started in a small garage back in 1988. That’s when Robyn and Robert Guyton sent out an invitation to anyone interested in organics and growing their own food to meet up. They set out 12 chairs in their garage, not hopeful of attracting a lot of people.

The building that houses the co-op came up for sale, so the members fundraised to buy it.

Sixty people turned up, from older folk who had grown organically all their lives, to young families more recently arrived who wanted to learn how to do the same.

“It was a symbiotic relationship,” says Robyn Guyton. “The older people knew how to grow and they already had the seeds and the berry bushes and fruit trees which they were happy to share cuttings from. They also knew how to compost and were keen to teach others.”

Two years later, the younger members of the group – many of whom were by then growing their own food – felt they would like to incorporate organic foods that couldn’t be grown in Southland, like oranges and kumara. To make this affordable, they decided to start a food sharing group, ordering in bulk, taking turns to divvy up the supplies, and jointly meeting the cost of freight.

The Guyton’s volunteered their garage again. It was requisitioned as a collection point for the incoming goods, and getting together to sort out the supplies made for a lot of fun times, especially for Robyn and Robert Guyton’s young children, Hollie, Terry and Adam.

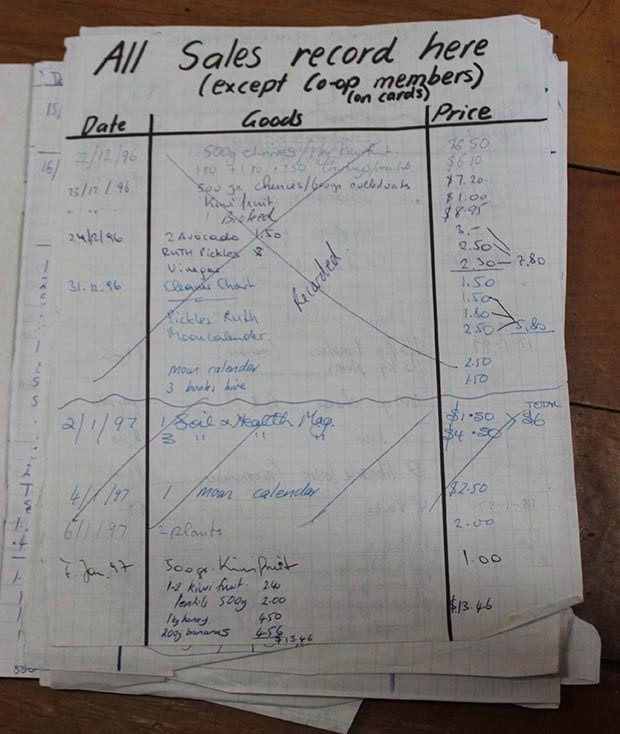

Notes in the old exercise books used at the time for record-keeping show the amazing amount of organisation and hard work involved, says Robyn.

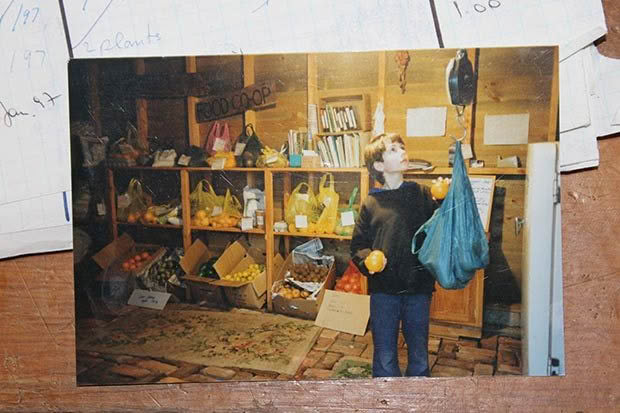

The Guyton’s humble garage was the starting point.

“There was a telephone tree to manage, orders to be collected and placed, goods to be unloaded, stored and weighed, compost scraps to be disposed of… the list was quite long. After a time, it became clear it was the same group of people that were doing all the work. So, after several years in the garage on the old model, we decided to take a new approach and to form a not-for-profit shop run by volunteers.”

Hand-written records, the starting point of the co-op.

Three premises and 26 years later, the operation runs quite differently.

Today, each person who works at the food co-op receives a discount of 2% per hour (up to a maximum of 15%) in return for their labour. In a sense, the premises acts more as a shop than an actual food co-op, although the name is retained in recognition of the original organisation’s aims.

The co-op shop in the mid-90s.

Around 25 helpers work each month at the co-op, some coming in once a month, others once a week.

The added advantage of the co-op’s present-day premises is that the shop is set up in the town’s Environment Centre, enabling an affordable space-sharing option while keeping the centre open longer than would otherwise be possible. The co-op has a natural kinship with the various groups that make use of the centre, including Southland Seed Savers (first established in 1999 to develop a network of non-hybrid seed sharing), and the Open Orchard project which aims to establish a diverse range of old varieties of healthy heritage fruit trees in Southland communities.

The shop is much bigger in 2017 than it was. Fresh, mostly locally-grown food is still the draw card.

Its spot in the local Environment Centre is currently surrounded by craft shops, an art gallery, a state-of-the-art museum, a supermarket, and thriving cafes serving locals and tourists alike.

On the day of NZ Lifestyle Block’s visit, the busy little seaside town of Riverton (population 1200) is positively buzzing. It’s only when you open the door of the food co-op and go inside that you feel you’re leaving the hustle and bustle behind and entering a space that looks, smells and feels more like the gentle general stores of a 1950s childhood. It’s reminiscent of the kind of places that once sold everything from jelly beans to boot laces, where passing the time of day was as important as making a purchase.

Volunteers Hollie Guton, Rosemary Todd, Karla Evans, Lynore McCabe and Robyn Guyton.

Comfortable sofas and soft chairs are drawn up around a log burner, banners hang from the ceiling, and photos, posters and information panels adorn the homely brick walls.

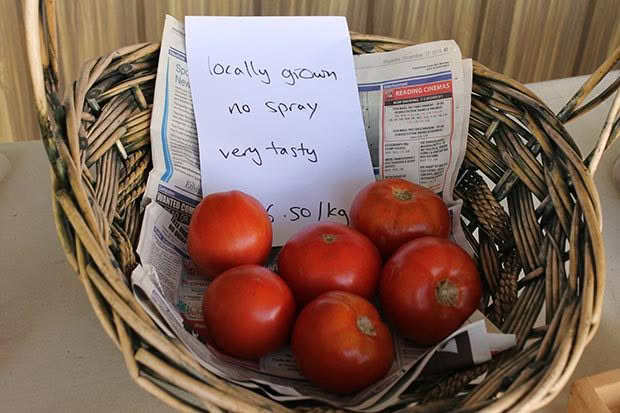

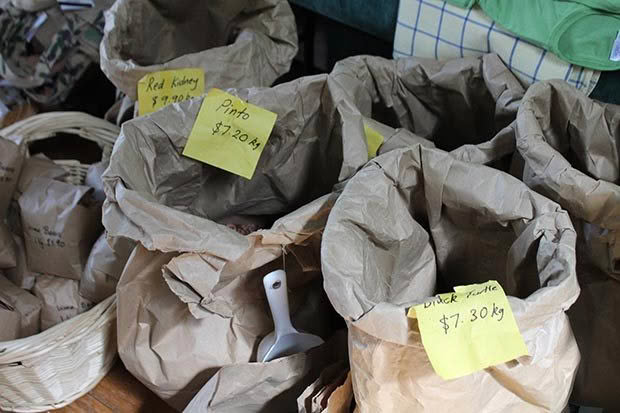

In one corner, a help-yourself library is generously stocked with books. Wicker laundry baskets and boxes spill over with vegetables, fruit and garlic, neatly displayed on the polished wooden floor. Sturdy paper sacks with rolled down tops are filled with dried peas and beans. Wooden shelves are filled with naturally perfumed soaps, balms and lotions, adding to the sense of peace

the place exudes.

Robyn Guyton still spear-heads the operation of this not-for-profit organic supplier, working hard since its inception 26 years ago. She is sitting on one of the sofas, surrounded by screen-printed green t-shirts. Daughter Hollie (now 21 and home from Otago University for the holidays) is busy tidying in the background.

Hollie was just two years old when she first began helping with the organic food supply. In those days of the garage, the organisation was less formal, more a food buying club than a co-op.

“We moved to Riverton for Robert’s teaching job and so I could be nearer my mum who lived in Southland,” says Robyn. “After two years, we realised we’d fallen in love with the place and didn’t want to leave. But there was a problem.

Comfortable chairs around the log burner.

“We weren’t conservative by nature, yet we felt we’d moved to a part of the country that was more white bread sandwiches and Coronation Street than we were comfortable with, and that if we wanted to stay, we’d have to instigate some changes.”

Those changes have resulted in a valuable community service, encouraging people to be more self-sufficient in food, and teaching them vital skills through seminars, workshops and other programmes.

Early this year the building that houses the co-op store came up for sale. The group had just weeks to raise the purchase price of $75,000. No problem. They raised $20,000 online in a month, helping to secure them the building, and when we last checked in, they had just a few thousand dollars left to raise to buy the building outright.

Ask Robyn what her own skills are, and her co-workers are quick to answer for her, labelling her ‘inspiring’ and ‘visionary’. Listening to Robyn talk about the co-op, you can also add calm, an attribute she no doubt requires when dealing with the various challenges which she says have, over the years, come in waves.

Naturally perfumed soaps, balms and lotions add to the sense of peace.

The latest challenge is how the co-op is to find time to answer the many emails it receives from media, and helping other groups to begin their own similar enterprise.

“Once, we could answer correspondence within two days. But now, especially since the co-op was featured in Country Calendar (in 2015) we’ve become inundated with requests for information, mentoring, and also to be available to media. It’s not easy to answer every enquiry so quickly any more. Somehow, we have to work out how to find the time to do everything else being asked of us. But we’ll find a solution. This is just another example of a challenging ‘wave’.”

When you open the door, you feel you’re leaving the hustle and bustle behind and entering a 1950s general store.

The co-op sells thousands of dollars of goods a year and can maintain a satisfying level of stock on its shelves at any one time. It still manages to maintain friendly relations with local business operators.

“(They) don’t regard us as competition because we serve a completely different group of buyers,” says Robyn.

“That’s a good thing but eventually I would like to see a complete reversal in the way we buy and sell food in this country – everywhere, in fact. There has only been a short period in history when our food hasn’t been grown organically – perhaps a period of no more than a hundred years. I’d like to see the situation change to a point where non-organic food carries the label ‘chemically grown’ and organic food is taken for granted and constitutes the bulk of what is available to the public. If people want to buy chemically-grown food, I’d like to see them having to set up a food-co-op in order to afford this.”

Until that day arrives, organic food is likely to be distributed in alternative ways, and Robyn has a few pointers if you’d like to see this happen in your town.

9 tips for starting a local food co-op

1. There is no ‘I’ in teamwork

While Robyn acknowledges she is the backstop behind the co-op, standing in for anyone who can’t make it at the last minute, she is quick to point out that the co-op works because members bring to it their own specific skills and no one is ‘power hungry’.

“The main thing is to make sure people are enjoying their work. We have one helper who likes organising shelves, another who is confident serving, and we employ a person for two hours a week to handle bill paying. It’s because of people like this that we can keep the co-op open seven days a week for 42 hours.”

2. One size doesn’t fit all

Tailor your organic food supply to suit the size of your community. Not every place needs a food co-op. All that may be required in your area is a telephone-tree-operated food-sharing club or the delivery of randomised organic produce boxes on a weekly basis. Look at models that have worked in similar communities.

3. Duty rosters are a basic

When divvying up duties, make sure no one person is landed with the bulk of the work or the organisation will soon collapse. Have back-up helpers who are available to take on jobs at short notice when another worker cannot make it to work.

4. The perfect premises

If you require premises, you may need to negotiate the use of a garage or similar building for food distribution. If your organisation needs to move into a more ‘retail’ part of town, give serious thought to ‘shop-sharing’. Approach the likes of a tradesperson who is using only a small portion of a building to store parts and equipment and who is probably able to open for only a few hours each week. Offer to keep the premises open for more hours in return for a reduced or nil-rental on space for a co-op to operate.

5. Be discerning

If the aim is to supply locally-grown organic vegetables, you can’t always insist on produce being officially ‘certified organic’ so learn to be discerning. Get to know your suppliers on a personal level and if you find they are caring for their soil (growing organically) and their plants are healthy, accept their goods and label them ‘locally-grown home-organic’.

6. Let your buyers/food sharers be the judge

If someone notices a product you’re buying contains an ingredient that’s not acceptable (palm oil, for example) or points out a product is being produced by marginalised labour, cease stocking it.

7. Locally sourced

Sell locally sourced goods wherever possible and recognise that this opportunity may change seasonally. Currently, the Riverton co-op sources lamb and beef from an organic grower in nearby Blackmount, and gets its organic pork from Riverton. Depending on the season, 25% of the vegetables stocked are grown in Southland, but the co-op would like to see this increase to 100%. One local supplier makes enough from her vege sales to pay for her family’s fruit purchases from the co-op.

8. Predict and prepare

Make a plan for ‘loss sharing’. When dealing with fresh produce, there will always be some waste. The Riverton Organic Food Co-op currently splits the loss 50-50 between suppliers, the co-op paying the supplier 50% of the value of the produce that is unsold.

9. Pricing plans

Think about how you will price your produce. The Riverton Organic Food Co-op asks suppliers to name their own price for fresh produce they are selling to the shop. Of this price, the co-op takes 10% for handling and administration and the government take 15%. Accept that prices for many goods will be higher when you live in more remote areas because of the cost of freight.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.